The George W. Bush Institute, in conjunction with The 74, a leading national education digital publication, is presenting a series of essays that look at the evolution and impact of the Dallas Independent School District’s Accelerating Campus Excellence (ACE) initiative. In this final installment, we look at the results ACE strategies have produced, the lessons learned from the program’s first four years, and how other districts might best emulate this model.

Data in the Moment: How Dallas ISD’s ACE Program Helps Students Progress

- Chapter One: The Power of Differentiation

- Chapter Two: Data Drives Educational Excellence

- Chapter Three: The Difference a Principal Makes

- Chapter Four: What Happens Next

No one can deny the impact the ACE model is having on underperforming campuses, particularly ones with long records of leaving students behind and unprepared for what comes next.

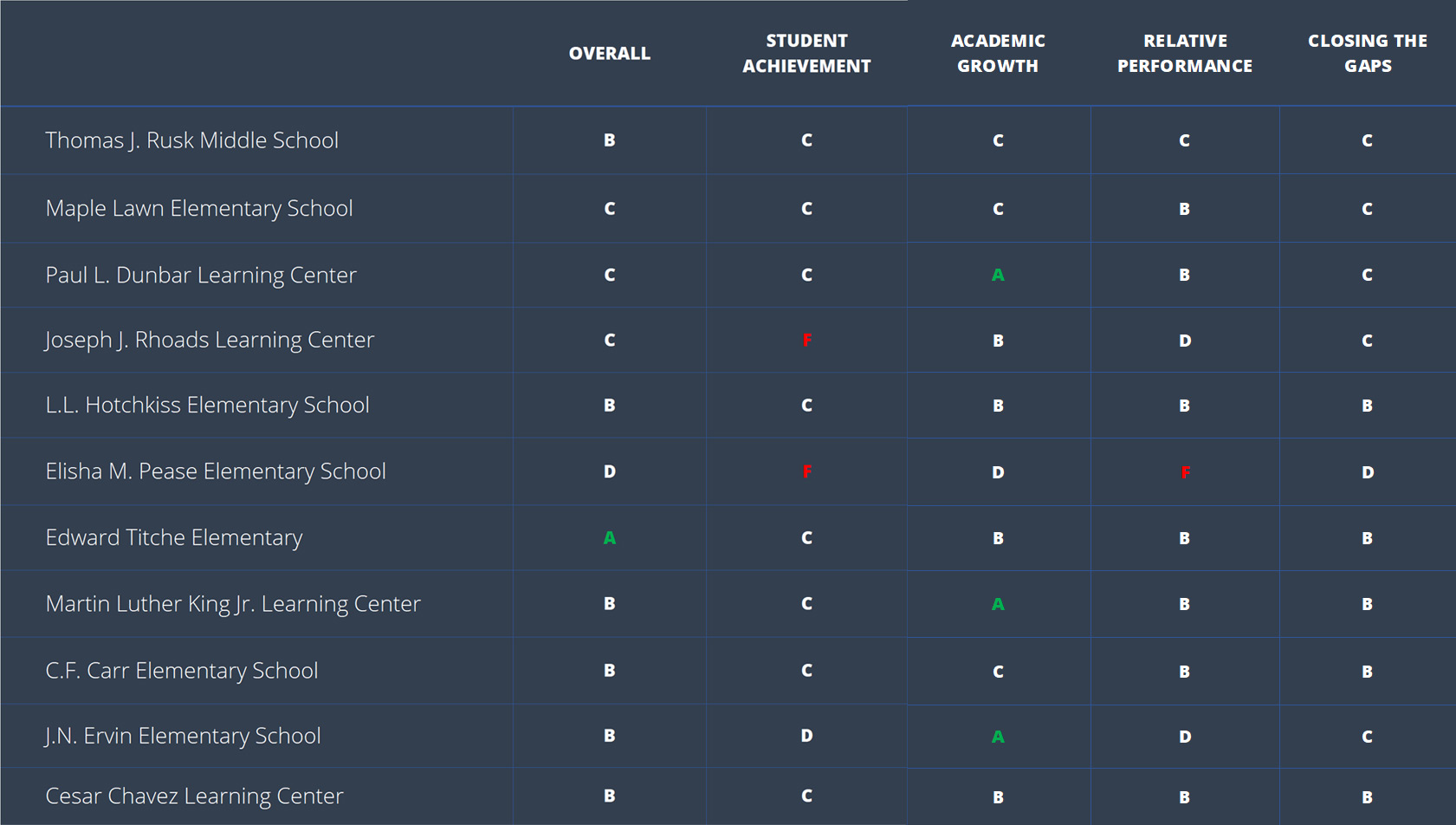

In the 2017-2018 school year, 62 percent of Dallas’ ACE schools earned an A or B grade from the Texas Education Agency’s annual rating. The participating ACE schools, which form their own feeder pattern, also earned more “distinctions” from the state than any Dallas Independent School District (DISD) feeder pattern. (The state awards distinctions for achievement in subjects like math, reading, and science.)

In 2018-2019, the overall results have been equally impressive: Six of Dallas’ 11 ACE campuses earned a B, while one campus was awarded an A. Only one school earned below a C, and that was Elisha Pease Elementary School, which received a D.

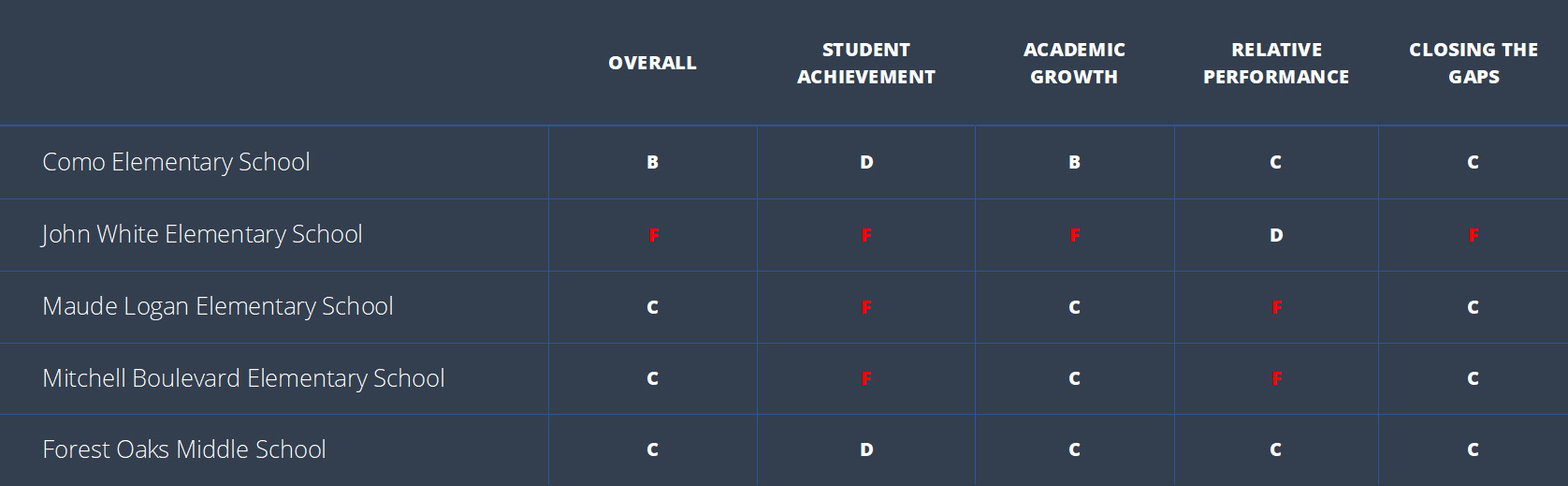

The results in Fort Worth are not as strong. Only one campus, Como, earned a B. Three got Cs, while one received an F. But here is the important part: For at least three consecutive years before entering the program, every FWISD Leadership Academy had been labeled a failing school. Now, slowly and incrementally, four of the five campuses are making progress.

Stay the course

Despite the success to date, this dual approach of using data and strong educator talent to improve student achievement will only work if the districts can hold firm with fidelity. Change comes within a system when there is a steady commitment to implementing strong practices along with dedicated resources of people, money, and time. Disciplined, consistent implementation of education interventions may not make for headline news. But, stability within a system is critical to ensuring that proven reforms last and student outcomes improve.

Maintaining the upward projection will especially be critical as schools move out of the ACE model. What happens then? Will the progress of their students slip away? And what might happen with the middle schools in these cohorts, which are often the most challenging to turn around and keep progressing?

Edwin Flores, the former Dallas school board president, has a direct answer: “We must keep our foot on the pedal.”

In practical terms, this means retaining strong school leaders, keeping instructional practices in place, giving incentives to strong teachers to stay on at struggling campuses, and providing services like instructional coaching and extended days.

Make no mistake: None of this work comes easily. Dallas already has had to trim some of its payments to ACE teachers participating in the third and current cohort of ACE schools, which includes the Martin Luther King Jr. Learning Center. Instead of paying every educator a bonus to teach in those ACE schools, a dozen or so highly-effective teachers receive them and form a leadership team that infuses the school with the program’s strategies.

Dallas school district leaders acknowledge that figuring out the transition is a work in progress. Improving the exit strategies for schools is a top priority.

The district’s attempt to address these realities starts with putting the transitioning campuses on a “fragile schools” list. A few of the campuses that went off the ACE list at the start of the 2018-2019 school year saw some academic gains slip away. One lost double-digit points in reading and two lost double-digit points in math.

The good news is those exiting schools still closed the academic gap between their own schools and the rest of DISD campuses by more than half since they started in the program in 2015. But to counter the backsliding, the district is paying mentor teachers $2,000 to work in fragile schools. A school can have a dozen or so mentors who will be able to continue ACE strategies. And all the educators in the transitioning schools are invited to attend Professional Learning Communities (PLC) meetings at other ACE campuses to learn and replicate on their home campus.

The transitioning schools also can keep their assistant principals and any teachers who wish to stay. The educators would lose their extra pay, which, of course, may cause some assistant principals and teachers to leave the school.

But an educator focus group conducted by Best in Class and the Dallas district reported that school culture and community were the most important factors for teacher retention. Teachers were more concerned about the quality of their principals than their stipends. “The biggest challenge after schools leave ACE,” Garrett Landry of the Best in Class partnership observed, “is the consistency of leadership.”

The principal’s role is so key that Dallas school trustee Dustin Marshall believes the district should continue the $15,000 extra stipend for principals to stay in their schools after their campuses exit ACE. That would mean less than $200,000 per year for the district, a fairly nominal sum given that the Texas Legislature approved money in its 2019 session to help ACE-like schools.

The investment certainly would be in students’ best interest. It would maintain consistency in leadership, which, in turn, would help retain quality teachers. It also would protect the district from losing the investment it has made in those leaders and educators and the progress of their students. (ACE costs run about $1,300 per student on top of standard per pupil funding.)

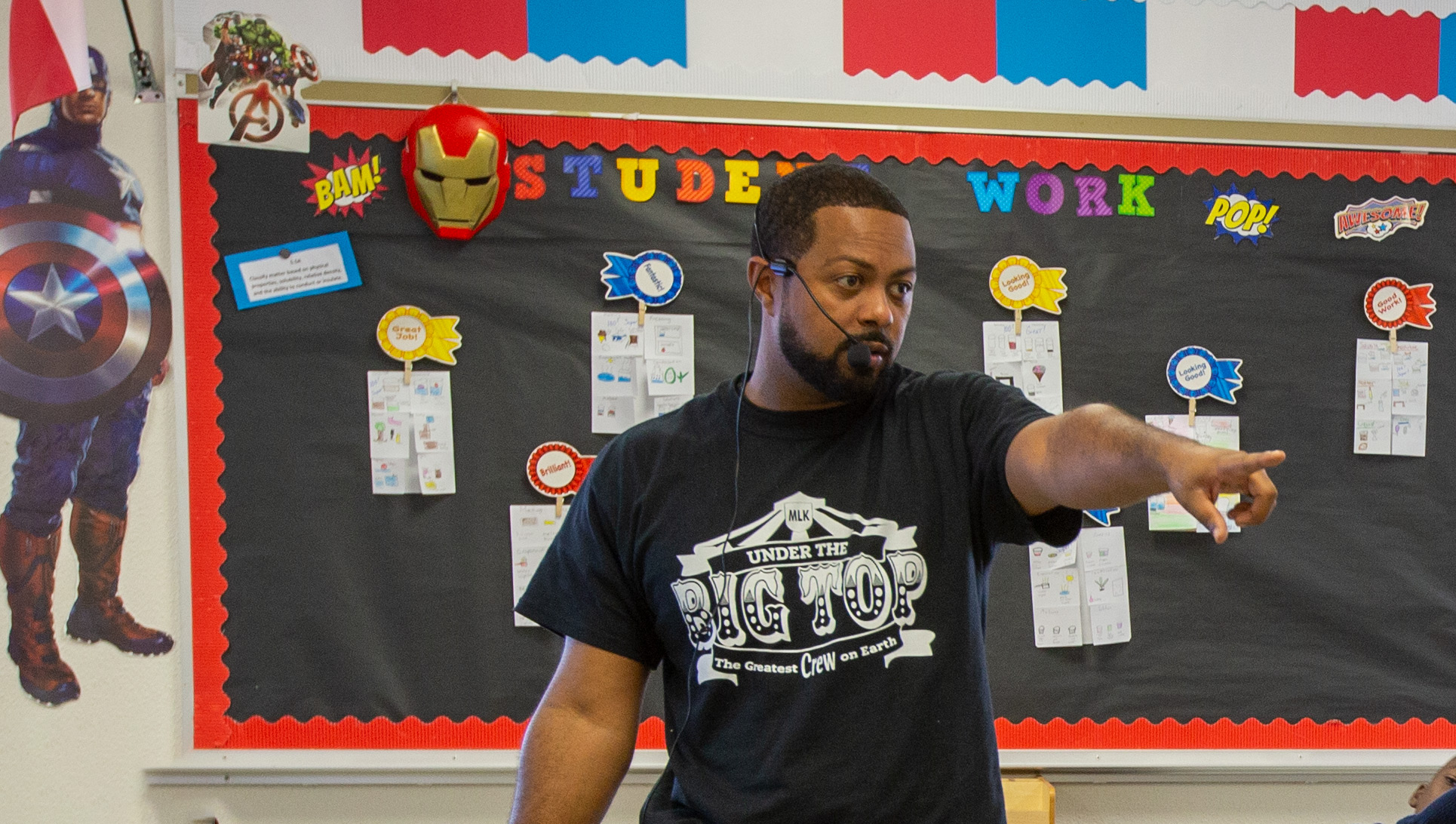

Another challenge for transitioning schools is that the skills of their leaders might be needed elsewhere. Half of the principals in the first ACE cohort were promoted to principal supervisors. And over the summer, DISD officials reluctantly decided they needed Rockell Stewart, principal of the MLK Learning Center in 2018-2019, to return to backsliding Billy Dade Middle School as its leader. (MLK’s assistant principal, Romikianta Sneed, has replaced Ms. Stewart.)

Lessons learned

Dade’s struggles highlight the particular challenge of transitioning middle schools. Commit collected data that shows reading and math scores in ACE middle schools improved at a lesser rate from 2015-2018 than they did in ACE elementary schools. Middle school reading scores rose by 15 percent during that time versus the 26 percent increase in elementary school reading scores. And middle school math scores rose by 22 percent versus 36 percent in elementary school math scores.

Faced with these realities, Dr. Hinojosa has pushed for training middle school teachers and assistant principals across the district in ACE practices. And the middle school struggles are among the reasons Dallas school leaders, as well as teachers, believe they now need exiting criteria along with entrance criteria for ACE campuses.

The recent educator focus group suggested such exit standards as an accountability rating of a B or higher; strong climate and culture scores; consistent leadership; and survey results from parents and students. Whatever standards are adopted, it would make sense for the district to gradually decrease resources to participating schools instead of simply ending the extra help.

These are the types of lessons other districts can learn from Dallas’ ACE model. This fall, eight Texas districts beyond Dallas and Fort Worth will operate their own version of this program. Together, the 10 districts represent about 10 percent of the state’s student body.

At the top of the list of lessons learned for any district attempting this model is to first have an effective way of differentiating leadership and instruction with a clear, multi-measure evaluation system. Teachers, principals, and parents all need to understand how teachers and principals are identified as eligible to be a part of an ACE campus. Shoulder tapping leaves out key talent and creates a culture where who you know is more important than what you know. As Mr. Marshall put it, “One step builds upon another. You cannot go to the end without going through the beginning.”

The second most important lesson is having a succession plan for exiting schools. Be prepared that some schools may need a long-term commitment, and all campuses will need a gradual release from extra supports.

The third lesson is related: Districts should see a model like this as a multi-year project. ACE practices are not a quick fix. Instead, they are great practices, done well consistently over time. Not all campuses go in the right direction all the time.

The fourth lesson is that states need to create by their own data-driven A-F systems that differentiate campuses. They should marry that accountability system with legislation that gives districts the flexibility and resources to succeed with an ACE-like system.

The investment might be substantial, but it will be more than worth it, especially if more schools within a district adopt the data-driven strategies. Doing so greatly increases the likelihood that all students will receive a year of learning for a year of classroom work.

And that, of course, is all that matters.

Continue reading Data in the Moment: How Dallas ISD’s ACE Program Helps Students Progress

Chapter One | Chapter Two | Chapter Three | Chapter Four