To fend off starvation while he was growing up in rural North Korea, Danny Lee remembers going into the mountains in search of small trees whose roots could be dug up, peeled, and boiled for hours into some form of sustenance.

“You have to survive by yourself,” he said. The North Korean economy had collapsed, there was no food available for purchase, and none of the neighbors had any money to buy anything he and his family might be able to scrape up to sell anyway. So to save Danny, his aging grandmother, and herself from starvation, Danny’s mother made the difficult choice in 2004 to cross the border into China to search for work and earn money to feed her family.

Five months later, 16-year-old Danny snuck into China himself to look for her. He found her hiding out from Chinese authorities while working at a nursing home for a pittance. So he joined her – giving residents showers, changing diapers and distributing food, as well as performing some farm labor.

The reason Danny and his mother had to hide is that China’s communist government officially deports escapees back to North Korea, where they and their families are frequently imprisoned and tortured by the autocratic regime in Pyongyang. But that doesn’t stop China from taking advantage of North Korean refugees terrified of repatriation, starvation, and torture.

“They give you a place to stay and free food, but not enough money – just $50 or $100 a month,” Danny said. “My mom said I’d work for free. They said, `I’m hiding you, giving you a place to live. There’s no reason to pay you.’”

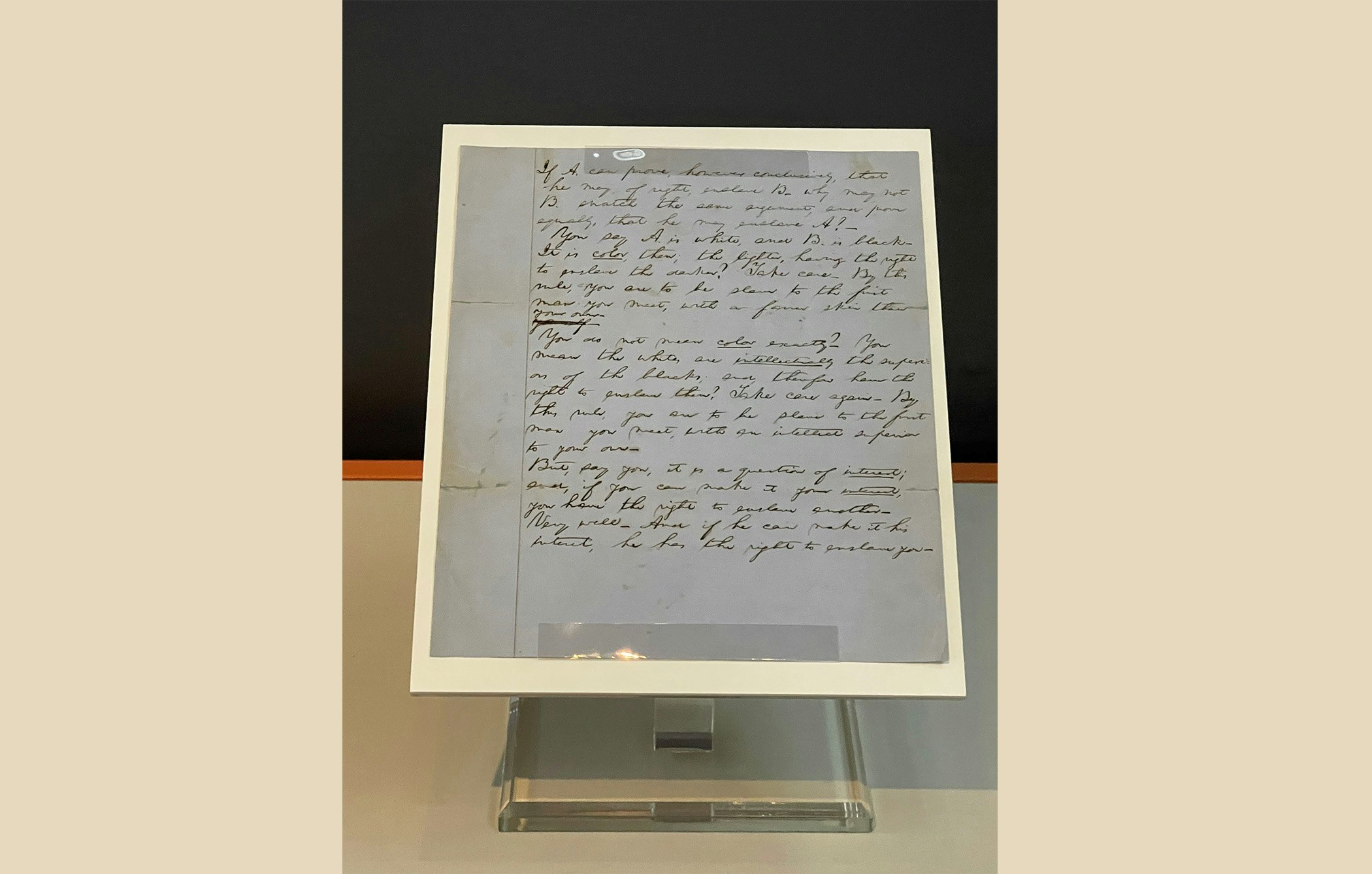

Beijing regularly turns a blind eye to – and even facilitates – the human trafficking of North Koreans, according to a recent report by Victor Cha, Senior Fellow at the George W. Bush Institute and Senior Vice President for Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and Katrin Fraser Katz, Adjunct Fellow at CSIS’s Office of the Korea Chair and Professor of Practice in political science at the University of Miami.

Both China and Russia take advantage of North Korean labor as well as engage in transnational repression and forcible repatriation of North Korean refugees to maintain good relations with the North Korean regime, make a profit, and align with a fellow communist state against the West, the report shows. They also help Pyongyang evade international sanctions and human rights obligations.

Hyun-Seung Lee’s upbringing in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang couldn’t have been more different from Danny Lee’s (they aren’t related). But he, too, ended up earning the wrath of the regime by seeking freedom and a better life.

Hyun-Seung grew up with access to food and an education. He joined the Worker’s Party of Korea – the country’s communist arm – and the military, which exposed him to the starvation and depravation facing most of the population. Then, at 29, he was offered the rare opportunity to study abroad – in China, where his immediate family already lived because of his father’s job.

“My studies raised doubts about my society,” he said. “North Korean propaganda is that our country isn’t developing because of the outside, because of the United States and the Western countries. But the whole belief system I had started collapsing. What they taught us, what they told us in the past, was a total lie.”

Then, in 2013, news broke that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un had had his uncle, Jang Song Thaek, executed for reasons that included “halfheartedly clapping,” to quote the state-run Korean Central News Agency. Most Western experts say that the execution and associated crackdown were so the younger Kim could consolidate power in a regime full of older men.

But these events shocked Hyun-Seung.

“Innocent people were killed,” he said. “My friend, a 23-year-old student, was sent to a prison camp because his grandfather was affiliated with the uncle. The grandfather was executed and the friend and the whole family were sent to a prison camp. My family and I were furiously angry at the regime. We heard they killed about 500 people that year. We didn’t know what to do. The whole atmosphere was one of darkness and fear.

“Eventually, my family came to the conclusion that we can’t serve this country, we can’t serve this leader,” Hyun-Seung said. “We have to do something for ourselves and our fellow people.”

They started making plans to flee. The family was already in China but didn’t trust the authorities there not to turn them over to North Korea. What followed could have come from a spy thriller: Fearing their telephones and home were bugged, they met in a park to discuss what to do. Ultimately, the South Korean government helped Hyun-Seung, his parents, and sister get out of China.

But the North Korean regime wasn’t done with them.

“The North Korean government showed my grandmother, uncle, and aunt on a North Korean TV show,” he said. “They publicly threatened us. Also, the South Korean government told us there might be an assassination attempt for my dad. They offered to provide protection, but we thought it was better to leave South Korea and came to the United States.”

Danny Lee also ultimately fled for freedom in the United States. He knew he had nothing to go back to after learning that his grandmother had died of starvation two months after he left for China. And one day, the pastor of a church he attended, who knew he was North Korean, offered to help.

“`You’ll face torture or jail or something if you’re sent back to North Korea from China, because they’ll think you betrayed your nation,’” he said the pastor told him. “`When you’re born, there’s a list of your birth, but when you die, there won’t be.’ I decided I didn’t want to stay anymore in a dark place and risk torture and punishment from the government.”

Danny came to the United States in 2007, studied English, obtained a work authorization, and is earning his GED, which he plans to finish this year. He lives in Chicago. Hyun-Seung Lee is currently working on a master’s degree in global leadership at Columbia University in New York. Both are recipients of the Lindsay Lloyd North Korea Freedom Scholarship, established by the Bush Institute in 2017 to help North Korean escapees and their children pursue higher education and build productive, prosperous lives as new Americans.

Neither he nor Danny has forgotten the plight of the people who remained behind in North Korea.

“My dad and I have discussed what we can do for the North Korean people in the future, and we believe that engaging with American politicians might be the best way,” Hyun-Seung said.

Despite the very real and ongoing threat of reprisal from the North Korean regime, Hyun-Seung and Danny say that it’s important to tell their stories, to push Washington and the international community for policies that ensure human rights for all North Koreans, whether at home, in China, or elsewhere in the world.