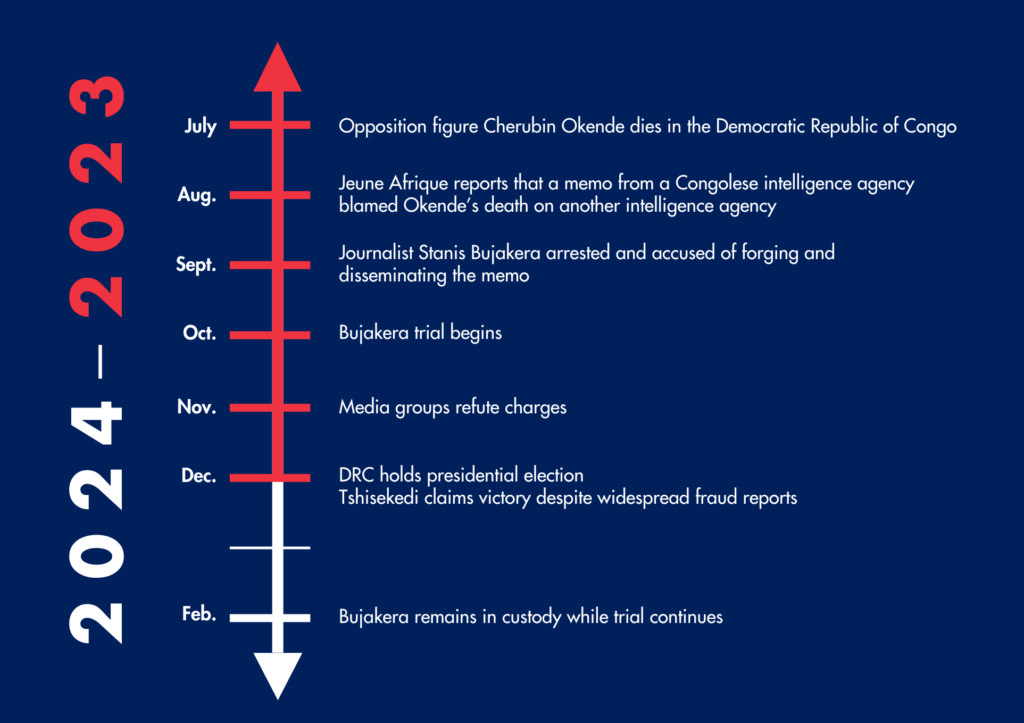

Stanis Bujakera, a reporter in the Democratic Republic of Congo, is on trial there on charges he forged and disseminated a memo by a Congolese intelligence agency about the death of the opposition figure Cherubin Okende in July 2023.

Bujakera was arrested Sept. 8 after the Paris-based publication Jeune Afrique, for which he writes, published an unsigned article about the memo by the National Intelligence Agency – known by its French acronym ANR. The document blamed Okende’s death on the DRC’s military intelligence agency.

Bujakera faces 10 years in prison for offenses including forgery, spreading false rumors, and transmitting false messages. His trial, which began on Oct. 13, continues. In addition to reporting for Jeune Afrique and Reuters, Bujakera is deputy editor of the Congolese online news outlet Actualities.cd.

Two independent journalistic investigations have dismantled the prosecution’s case about the memo and its dissemination, including the government’s claims to have linked the document to Bujakera’s phone.

Bujakera’s arrest effectively sidelined him during President Felix Tshisekedi’s campaign for a second term in the December 2023 presidential election. It also threw up a smokescreen around the murder of Okende, a former minister and opposition figure allied with Moises Katumbi, Tshisekedi’s main challenger.

Tshisekedi claimed to have won 73% of the vote in the December election despite widespread reports of fraud, faulty ballots and voter ID cards, and polling stations that did not open. The country’s largest independent monitoring group, the National Episcopal Conference of Congo (CENCO) declared the polls an “electoral catastrophe.” According to CENCO and an analysis by the Financial Times, Tshisekedi’s first election to the presidency, in 2018, was also fraudulent. Both found that Martin Fayulu actually won the 2018 election by a wide margin.

Nevertheless, Tshisekedi continues to enjoy U.S. support as the United States competes with China for influence in the DRC – at least in part because of the country’s vast mineral resources. The DRC has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, which is essential to lithium-ion rechargeable batteries in smartphones, laptops, and electric vehicles.

As important as such minerals are, prevailing in the strategic competition with China in the DRC, a country of 100 million, and throughout the world depends on American support for press freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. These offer the best alternative to China’s authoritarian vision and coercive economic diplomacy that benefit corrupt elites in the DRC at the expense of its people.

The death of an opposition figure

Bujakera’s arrest was set in motion when Okende’s body was found on July 13. Jeune Afrique published an unsigned article on Aug. 31 reporting on the contents of a two-page memo, dated July 14, prepared by ANR.

The ANR memo cited street children who saw Okende in his car in the parking lot of the Constitutional Court, according to Jeune Afrique. The ANR memo also stated that uniformed agents of the DRC’s military intelligence agency approached and entered Okende’s car, argued with and threatened him. The car then drove off, with Okende inside. Military intelligence agents “ended up hooding his head with gag, and, as a result, he died as a result of suffocation,” Jeune Afrique reported, citing the ANR memo.

Several days later, Congolese police arrested Bujakera while he was embarking on a reporting trip to the DRC’s southeast. Since then, he has been held in a communal section of the capital Kinshasa’s notoriously overcrowded Makala prison.

The government’s case falls apart

Investigations by the press freedom advocacy group Reporters Without Borders (in French, RSF) and Congo Hold-up consortium in cooperation with Jeune Afrique have demolished the government’s claims that Bujakera forged and shared the ANR memo.

After conducting its investigation in Kinshasa, RSF concluded the intelligence memo is authentic.

“There is no doubt in our minds that it is an ANR document and forwarded by the ANR,” RSF wrote, “even if we cannot judge the veracity of its content” – that is, the memo’s account of how Okende died.

Rebutting the government’s claim that Bujakera fabricated and distributed the memo, RSF’s report also established that “the memo had been circulating among security specialists, embassies, and certain media outlets before Bujakera and Jeune Afrique learned of it.”

The media consortium Congo Hold-up – in cooperation with Jeune Afrique – also discredited the government’s claims to have linked the document to Bujakera’s phone through encrypted Telegram and WhatsApp applications. Telegram rejected the government’s claims as “technically impossible,” while WhatsApp owner Meta said it was “not possible.” The companies further explained their products are designed to prevent messages from being traced, that they do not cooperate with law enforcement agencies, and they did not provide any data to the DRC government.

For its investigation, Congo Hold-up consulted the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, which has analyzed authoritarian regimes’ use of technology and digital information against journalists and dissidents. Citizen Lab’s Greg Miller found the prosecution’s claims regarding the journalist’s phone “not credible” and “fabricated.” However, the defense has been unable to present expert testimony of this type, and the prosecution is relying on an “expert” lacking in credentials, according to Congo Hold-up.

Why was Bujakera singled out with nonsensical claims?

The government’s interest in sidelining Bujakera is clear. Bujakera, 33, is a prominent journalist who enjoys the largest following in the DRC on X, formerly Twitter. According to Fred Bauma, a human rights activist and Director of the Congolese think tank Ebuteli, “holding him is preventing millions of Congolese access to credible information. It hurt the political debate during the last elections.”

Bujakera was born and raised in Kinshasa the son of a pastor and is a devout Christian. He left his university studies to accept an internship with the radio station RTVS1 and went on to help launch Actualite.cd.

Even in his 20s, Bauma told me, Bujakera was “young and already courageous.” Despite the prominence he has attained, “still, he is very open and humble,” Bauma said. “The funny thing is that even when he is in the U.S., where his family lives, he will break more news on politics than people in DRC.” Bujakera has permanent residency in the United States.

The allegations lodged against Bujakera aren’t the first time the government has moved against him. Last March, the government attempted to prosecute him for tweeting about a council of ministers meeting. The case was abandoned when it was shown that the information was already posted on a government website.

Pressure on journalists has increased in the DRC under Tshisekedi’s rule, said Jonathan Rozen of the Committee to Protect Journalists: “Stanis’s case is the continuation of a trend,” Rozen told me, “but it is even more serious because of the prolonged detention.”

The CPJ reported attacks and detentions of journalists by DRC security forces during the election campaign and the detention of the reporter Blaise Mabala on Jan. 24.

Meanwhile, Okende’s murder remains unsolved. The investigation report has not been made public. Nor has the autopsy, which could resolve confusion over the cause of Okende’s death. The prosecution initially stated he had been shot.

Tshisekedi suggests he might free Bujakera

“President Tshisekedi has repeatedly stated that Stanis’s detention does not please him [and] has hinted that once reelected, he might make a gesture in favor of his release,” Francois Soudan, Managing Editor of Jeune Afrique wrote to me. “We are waiting for this gesture.”

In the meantime, Soudan expects the United States and other countries to emphasize in their interactions with Tshisekedi and his government “the need to respect freedom of expression, the presumption of innocence, and the fact that no journalist should be imprisoned for an alleged offense of this type.”

Damon Wilson, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, which works with partners in Congo to support free elections, credits the DRC with some progress in recent years.

“Compared to its neighbors, the DRC is more open, there’s more political space, an ability to express your views, a diverse, competitive media,” he said. “That said, DRC remains a predatory, kleptocratic state.”

Only by dismantling that, he told me, can promises made for improved education, health care, employment, and infrastructure be fulfilled.

Nevertheless, Wilson told me, the prosecution of Bujakera sends a worrying signal. “Rather than deal with the assassination in a way that reinforced confidence as Congo headed into an important election, the government doubled down and targeted Bujakera rather than the assailants. It reeks of the old Congo under [former President Joseph] Kabila rather than the evolving Congo that Tshisekedi says he is trying to create.”

The outlandish events of Bujakera’s prosecution are more appropriate to a movie thriller than real life in a country whose president pledged to support the freedom of the press.

The United States has a vital interest in Bujakera’s freedom and in the expansion of press freedom and human rights as it competes with China for influence in the DRC and around the world. The Biden Administration should do its utmost to gain the release of Stanis Bujakera, a permanent U.S. resident, as well as a distinguished reporter. Until he is freed, his unjust detention and trial should have consequences for relations between Washington and Kinshasa.