The United States economy is back to full employment; with the jobless rate well below 5 percent, employers are quick to gripe about difficulties finding qualified workers. Yet immigration from Mexico, historically our main source of foreign labor, is in decline and unlikely to reverse course.

“You got what you wanted! But you lost what you had!”

Friends on the Other Side, “The Princess and the Frog”

The United States economy is back to full employment; with the jobless rate well below 5 percent, employers are quick to gripe about difficulties finding qualified workers. Yet immigration from Mexico, historically our main source of foreign labor, is in decline and unlikely to reverse course.

The U.S. economy has long relied on labor flows — mostly unauthorized — from Mexico. Mexican workers mostly came illegally as the existing immigration system reserves most legal avenues for family members of U.S. citizens. Outside of agriculture, just one seasonal worker program exists for low-skilled Mexican workers, but is capped by fixed quotas and, thus, allows for little growth. Meanwhile, the “NAFTA” (TN) visa is only for high-skilled workers, and just 10,000 such visas are issued annually to Mexican professionals.

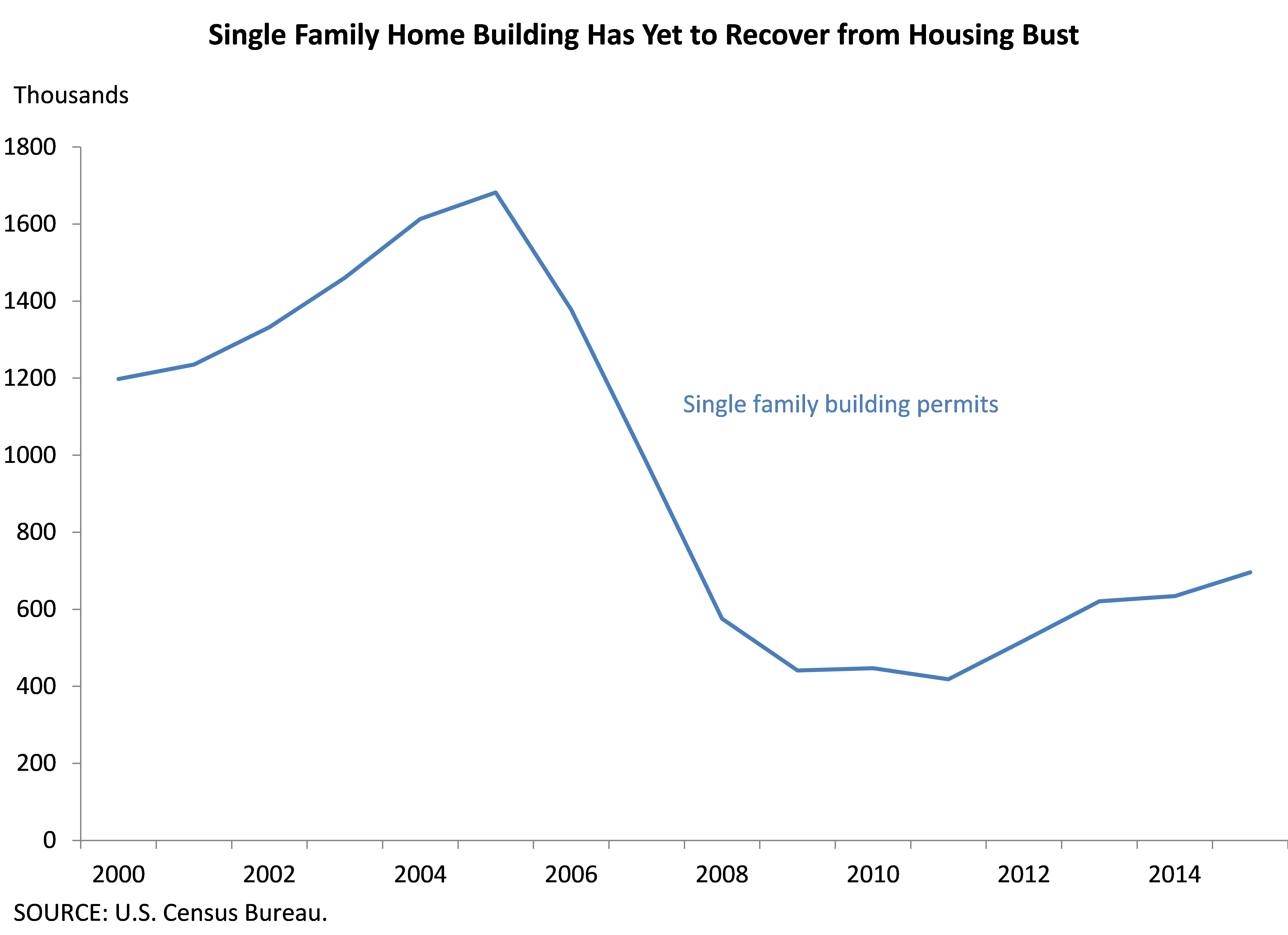

The housing bust, the financial crisis, and ensuing recession were devastating for Mexican immigrants and put a serious damper on migrant inflows.

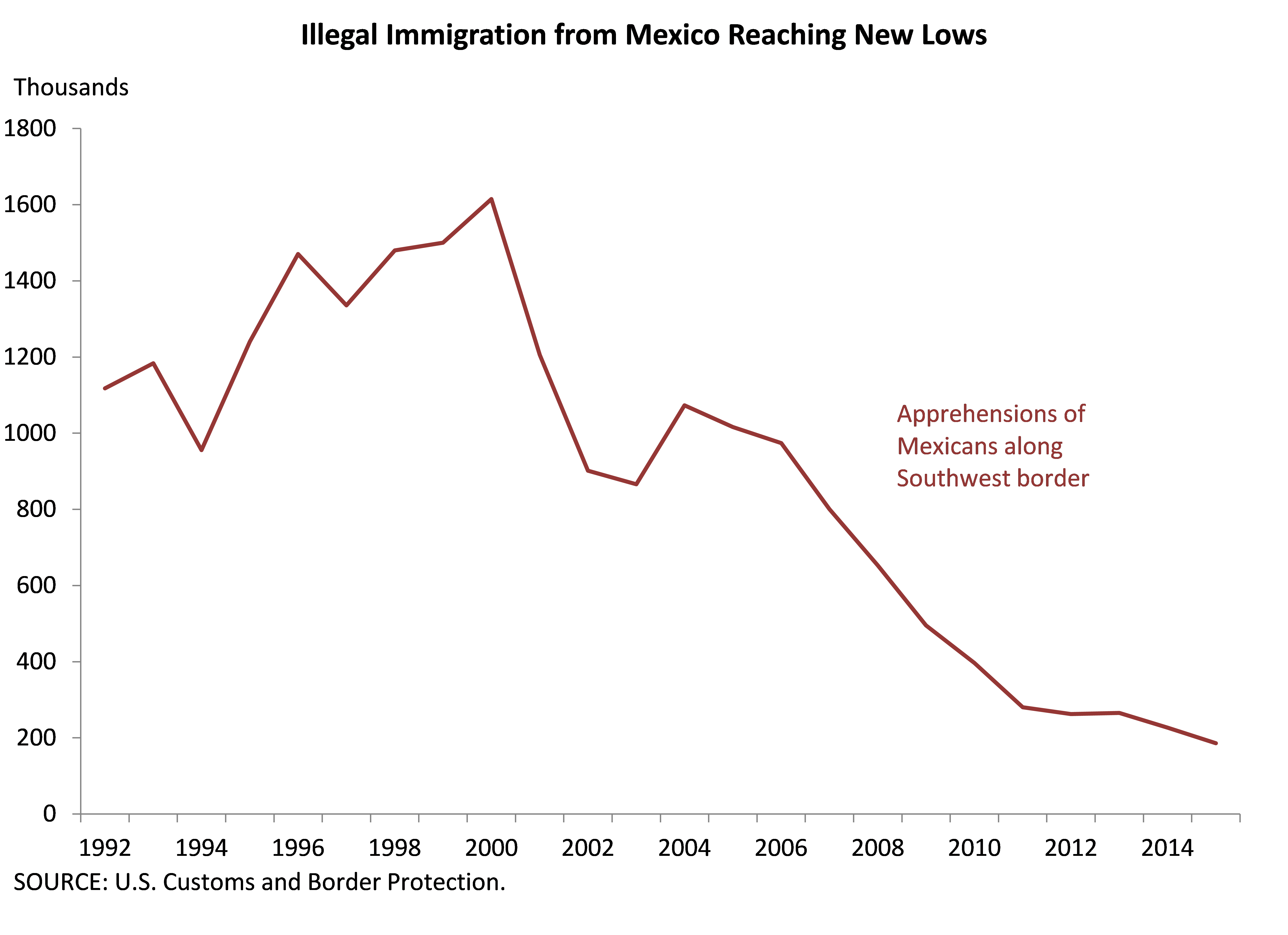

Border Patrol apprehensions of Mexican border crossers, a proxy for illegal immigration, are down almost 90 percent from their peak in 2000 (Chart 1). At less than 200,000 apprehensions in fiscal 2015, the Border Patrol today intercepts about as many migrants as it did in the early 1970s, before the era of mass Mexican immigration. In a telling sign of how radically immigration patterns are shifting, recent immigrants from China outnumbered those from Mexico in 2013, as did new arrivals from India.

Mexico-U.S. immigration has always been about workers flowing north to fill the types of jobs that Americans eschew. The first big push came in the early 1900s. Populating the Southwest meant surging demand for workers, and U.S. labor recruiters reached deep into Mexico to convince rather reluctant workers to come north to labor on railroads and ranches. The Mexican Revolution and ensuing unrest sped up U.S. settlement, quickening further as Congress moved to restrict European immigration by passing strict quotas in 1921 and 1924.

Mexico-U.S. immigration has always been about workers flowing north to fill the types of jobs that Americans eschew. The first big push came in the early 1900s. Populating the Southwest meant surging demand for workers, and U.S. labor recruiters reached deep into Mexico to convince rather reluctant workers to come north to labor on railroads and ranches. The Mexican Revolution and ensuing unrest sped up U.S. settlement, quickening further as Congress moved to restrict European immigration by passing strict quotas in 1921 and 1924.

When Europeans stopped coming but the U.S. economy continued growing, Mexican workers filled the void. The Mexican immigrant population surged 29 percent between 1920 and 1930, a trend that would end with the Great Depression and ensuing mass expulsion of Mexicans —many of them U.S. citizens — in the 1930s.

World War II and the Bracero Program, a U.S.-Mexico guest worker program intended to relieve farm worker shortages during the war, revived Mexican labor flows and set the stage for what would later become sustained mass immigration. U.S. employers again played an important part.

In an interesting historical twist, the so-called Texas Proviso — part of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act — ensured that U.S. employers would be off the hook for hiring undocumented workers. This provision was long lasting, in effect until the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA). That law legalized 2.3 million Mexican immigrants but, in exchange, mandated employer sanctions for firms that hired unauthorized workers. Sanctions were rarely enforced so, instead of ending illegal immigration, IRCA spurred it.

When immigration flows were at their peak, nearly a half-million Mexicans arrived on net —meaning gross inflows may have been closer to one million. In a stunning reversal, demographers estimate that the net inflow since the Great Recession, 2009–14, has been negative.

Why migration slowed down

After decades of mass Mexico-to-U.S. migration, why did it suddenly end? Several push and pull factors played a role.

Most obvious is stagnation in the U.S. construction industry since the housing bust of the mid-to late-2000s. Before the downturn, nearly one-fifth of undocumented Mexican men were initially employed in construction, but 2015 activity in the home building industry was nearly 60 percent below its prerecession peak (see Chart 2). All told, the housing bust, the financial crisis, and ensuing recession were devastating for Mexican immigrants and depressed migrant inflows.

Intensified border and interior enforcement also contributed to falling inflows. While many interior enforcement programs have recently been rolled back, locally implemented federal initiatives such as Secure Communities helped propel removals of Mexican nationals to record highs — nearly 300,000 per year — while they were in effect.

Border enforcement has also proven a powerful deterrent. Although critics decry the “porous border,” it has never been as secure as it is today. Whether it is the 20,000 Border Patrol agents, the hundreds of miles of fences, or the drones, sensors, and cameras used to detect people entering the U.S. illegally, crossing has become difficult and perilous across the Southwest border.

Although far fewer migrants attempt the trek, border crossing deaths still number between 200 and 300 per year. They suggest death rates are up sharply. Extensive fencing and interior checkpoints ensure migrants walk days in the desert to reach their destination, in a terrain that is hostile to humans under even the best conditions. The effectiveness of security on the border is best reflected in the prices smugglers charge Mexicans for guiding a clandestine crossing —about $5,000, up from less than $1,000 in 1990.

The effectiveness of security on the border is best reflected in the prices smugglers charge for guiding a clandestine crossing — about $5,000, which is up from less than $1,000 in 1990.

Improving economic conditions in Mexico are an additional factor slowing emigration. While wages today are rising only slowly in real terms in Mexico, this is a big improvement over falling inflation- adjusted wages in times of mass outmigration, such as in the 1980s and 1990s.

What’s more, job creation in the formal sector has been robust, implying more access to employment with fringe benefits and pensions. Inflation and government debt have been low and stable, the result of central bank and public finance reforms in the early 1990s, and the government has put a social safety net in place, with health care and welfare programs for the poor and elderly.

Changing Mexican demographics is not only an additional reason why immigration is off its highs; it is the main reason mass migration will not resume in the future. Mexican women today average between two and three children, just slightly more than U.S. women.

This is a far cry from the 1960s, when six to seven children was the average. After the fast-growing 1950s and 1960s were over, there was no way the Mexican labor market could absorb such large cohorts of young men and women. The natural escape was to the north, where young workers readily found jobs.

Paradoxically, the end of large-scale Mexican migration has not brought calm and stability to the Southwest border or quieted the immigration debate. Violence and corruption in Central America is inciting mass emigration from there, filling some of the void left by disaffected Mexican workers who have stopped coming. However, many of the Central American migrants are women and children, who come here to seek asylum.

It is increasingly clear that legal pathways for Mexican workers must be expanded if the goal is to rekindle Mexico-to-U.S. labor flows, particularly of low-skilled workers who currently lack legal alternatives.

Faced with prohibitively expensive and perilous border crossings, tougher interior enforcement, and the lackluster construction sector, it is not surprising Mexicans increasingly choose to stay home. Although wages remain far lower in Mexico, employment opportunities are increasing and the quality of life has improved — consumers have access to credit and homebuyers to mortgages and social programs cover more people than before.

It is increasingly clear that legal pathways for Mexican workers must be expanded if the goal is to rekindle Mexico-to-U.S. labor flows, particularly of low-skilled workers who currently lack legal alternatives. A temporary worker program would bring workers legally and safely, benefiting both sides of the border.

Absent such changes, the U.S. economy will adapt to a state of chronic shortages of low-skilled labor in a number of ways. In the service sector, higher prices, longer waits, and more self-service. In the goods sector, including agriculture, more production will be offshored and goods imported, while technology will increasingly replace workers where possible. Wages may rise for low-skilled workers, but it’s unlikely to attract many natives back into the types of occupations immigrants have dominated for decades. A well-run worker program, meanwhile, is likely to attract investment, increasing demand for both native and foreign workers.

Economic growth can slow due to weakening demand, but it can also be constrained by low labor supply. As the unemployment rate slips ever lower and labor-intensive industries struggle to find workers, the time may well be right for lawmakers to craft legal ways for Mexican workers to come.

Pia Orrenius, vice president and senior economist at the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, is a member of the Bush Institute’s Economic Growth Initiative’s Advisory Council.