Naturalization is not just about the immigrants. It is about the contributions and vitality the United States gains each time an immigrant becomes a citizen.

When U.S. immigration policy is at its best, it creates new Americans eager to contribute to our great country, strengthens our democracy, and fills critical gaps in the labor force, making us more competitive in the global economy. But we have lost sight of that in recent years, branding immigrants a drain on our society and increasing roadblocks along the path to citizenship.

The truth is immigrants punch above their weight in economic terms. They enhance our communities. And they have been enriching American culture for our entire history. They are our neighbors and essential workers — our doctors, innovators, meatpackers and farm workers. It is to their advantage — and the nation’s — that they become citizens.

Nearly 9 million permanent residents are eligible to apply for citizenship each year and around 700,000 have done so annually since 2000. Many of them wait months to take the oath of citizenship after applying for naturalization. The COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing shutdowns have exacerbated this backlog and increased wait times significantly. It is in the best interest of the United States, local communities, and businesses to promote naturalization and support immigrants on their journey to citizenship.

EXAMINING IMMIGRANTS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Economics

Immigrants are an economic force for the United States. Entrepreneurially and innovatively, they have made their mark on our country for decades.

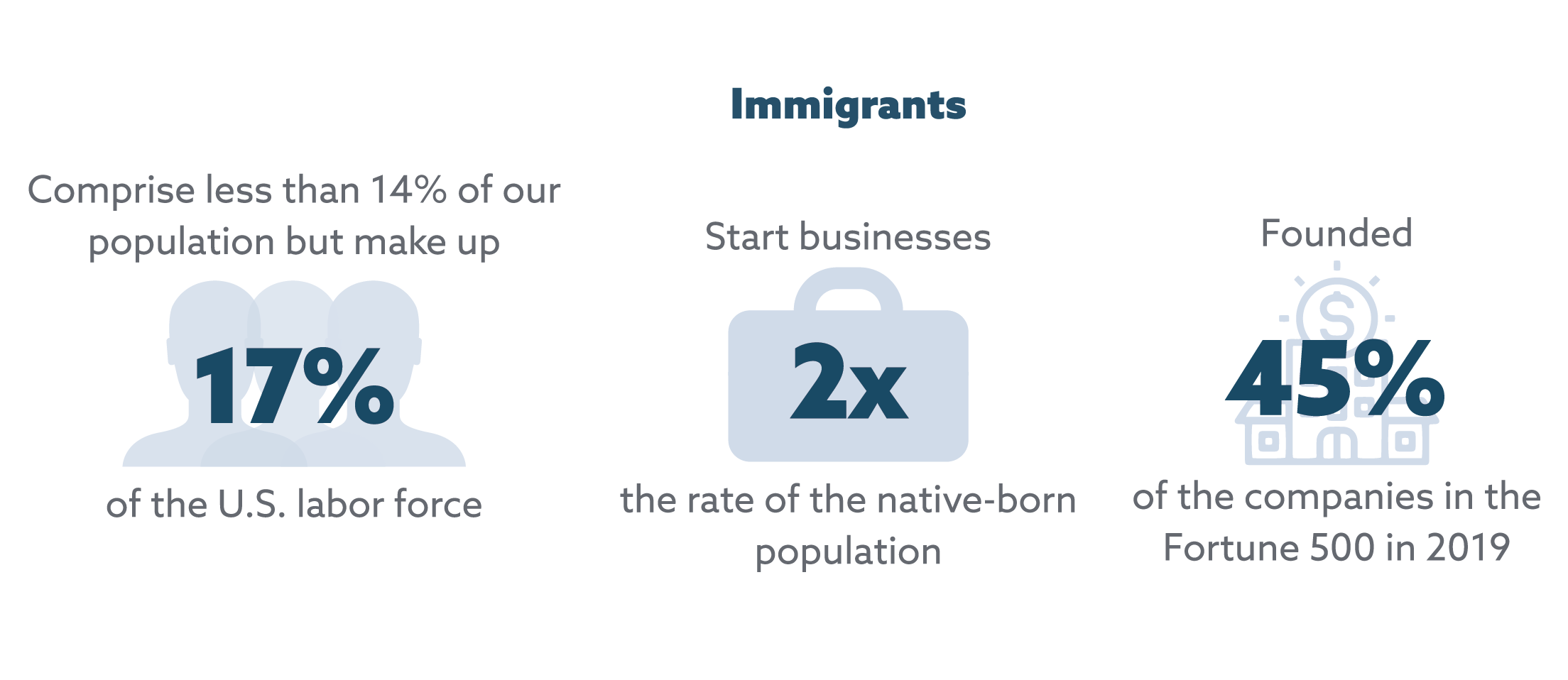

Immigrants comprise less than 14% of our population but make up 17% of the U.S. labor force. They start businesses at twice the rate of the native-born population and they and their children founded 45% of the companies in the Fortune 500 in 2019.

Immigrants are twice as likely to be granted patents than native-born Americans.

Some of our best-known tech companies were founded by immigrants, including eBay, Google, Tesla, and Yahoo.

Culture

Immigrants have contributed to American culture since its founding. So many things that are quintessentially American were brought to the United States from all corners of the world. Americans have an endless capacity to adopt our new residents’ foods and customs as our own, enriching our daily lives.

Immigrants and their children have been influential in nearly every aspect of our culture, from the arts to science to sports. One of America’s most famous architects, I.M. Pei, was a Chinese immigrant. American ballet would not be as important as it is today without Russian-born George Balanchine. Our movie and television industries have been blessed with immigrant talent for decades, from people like Frank Capra, who directed It’s a Wonderful Life, to actors Charlize Theron, Sofia Vergara, Mila Kunis, Kumail Nanjiani, Michael J. Fox, and Jim Carrey, among countless others. There are many influential immigrant designers in American fashion: Diane von Furstenberg, Oscar de la Renta, Carolina Herrera, Jason Wu, Joseph Altuzarra, and Prabal Gurung to name just a few.

Immigrants have risen to the highest levels of many sports in the U.S. Notable athletes include Dirk Nowitzki, Annika Sorenstam, Albert Pujols, Monica Seles, Ezekiel Ansah, David Feherty, Dikembe Mutombo, Hakeem Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing, Mariano Rivera, Yasiel Puig, Felix Hernandez, and Sammy Sosa.

We see immigrants impacting American journalism as well. Jorge Ramos, Arianna Huffington, and Fareed

Zakaria are naturalized citizens who are household names.

Immigrants who have positively impacted American science are too numerous to count. Examples include such noteworthy scientists as Albert Einstein and Alexander Graham Bell. Perhaps one of the most influential immigrants in our history was Andrew Carnegie. Born in Scotland, he came to the United States as a child and eventually became one of the wealthiest people in America. He later become a prominent philanthropist1, helping establish thousands of public libraries in the United States.

American Ideals

Immigrants, especially naturalized citizens, choose to be Americans. They choose our democracy, our freedoms, and our culture. It should come as no surprise, then, that immigrants are as patriotic or more patriotic than native-born Americans.

To measure this, Alex Nowrasteh and Andrew C. Forrester of the Cato Institute analyzed responses to the General Social Survey. Immigrants overall were prouder of the United States than native-born Americans were. They are more likely to believe that the United States treats all groups equally than their native-born counterparts. They are less ashamed of the United States than the native born by a large margin. And more immigrants than native-born Americans think the world would be better if citizens of other countries were more American.

Immigrants’ patriotic feelings about America are not the entire story, however. The General Social Survey also found that immigrants trust American institutions — such as Congress, the Supreme Court, and the presidency — at much higher rates than native-born Americans do. Immigrants are injecting much-needed support for these institutions. Confidence in U.S. democratic institutions has been on the decline for several years. It is notable that immigrants who chose the United States have such a positive outlook on our government, particularly when the native-born attitudes are trending negatively.

COVID-19

Immigrants have also been key to the U.S. fight against COVID-19.

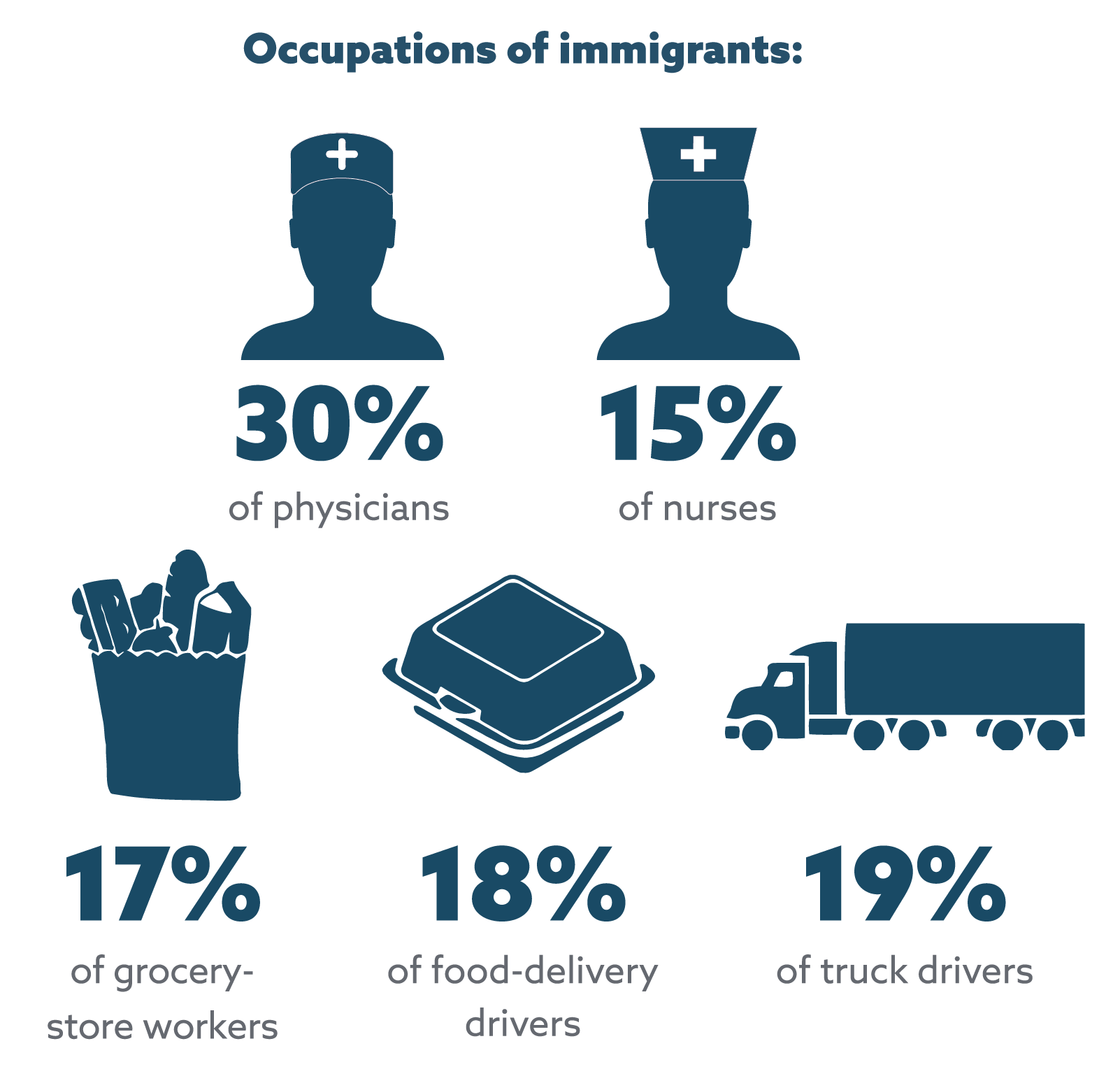

Nearly 30% of physicians in the U.S. are foreign born, as are more than 15% of registered nurses. The current pandemic has also spotlighted workers we do not think about enough: grocery store stockers and clerks, delivery drivers, truck drivers, agricultural workers, meat-plant workers, and other personnel providing essential services. Immigrants tend to be overrepresented in these professions, too: Nearly 17% of grocery-store workers, 18% of food-delivery drivers, and 19% of truck drivers are foreign born.

Additionally, almost a third of meat-processing plant workers were born outside the United States, and many of the men and women working at these jobs are refugees.

The fruits and vegetables keeping us nourished during the pandemic are picked almost entirely by immigrants who are in the country without legal authorization, who have no path to citizenship under U.S. immigration law. More than 70% of farm workers are undocumented.

Indeed, many of the services we use to keep us connected and safe during the pandemic were started by immigrants. Zoom and Postmates are just two examples.

Even the N95 mask, one of the most important tools frontline health workers have when treating COVID-19 patients, was invented by Taiwanese immigrant Peter Tsai.

Immigrants are incredibly important to American society. But they cannot fully participate in American civic life, and in our economy, if they do not naturalize.

THE ADVANTAGES OF CITIZENSHIP

Economic Benefits

Naturalized citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green card holders) make up nearly three quarters of immigrants in the United States. Advantages accrue to immigrants who become American citizens, making the immigrant population that is eligible to naturalize an untapped resource for America.

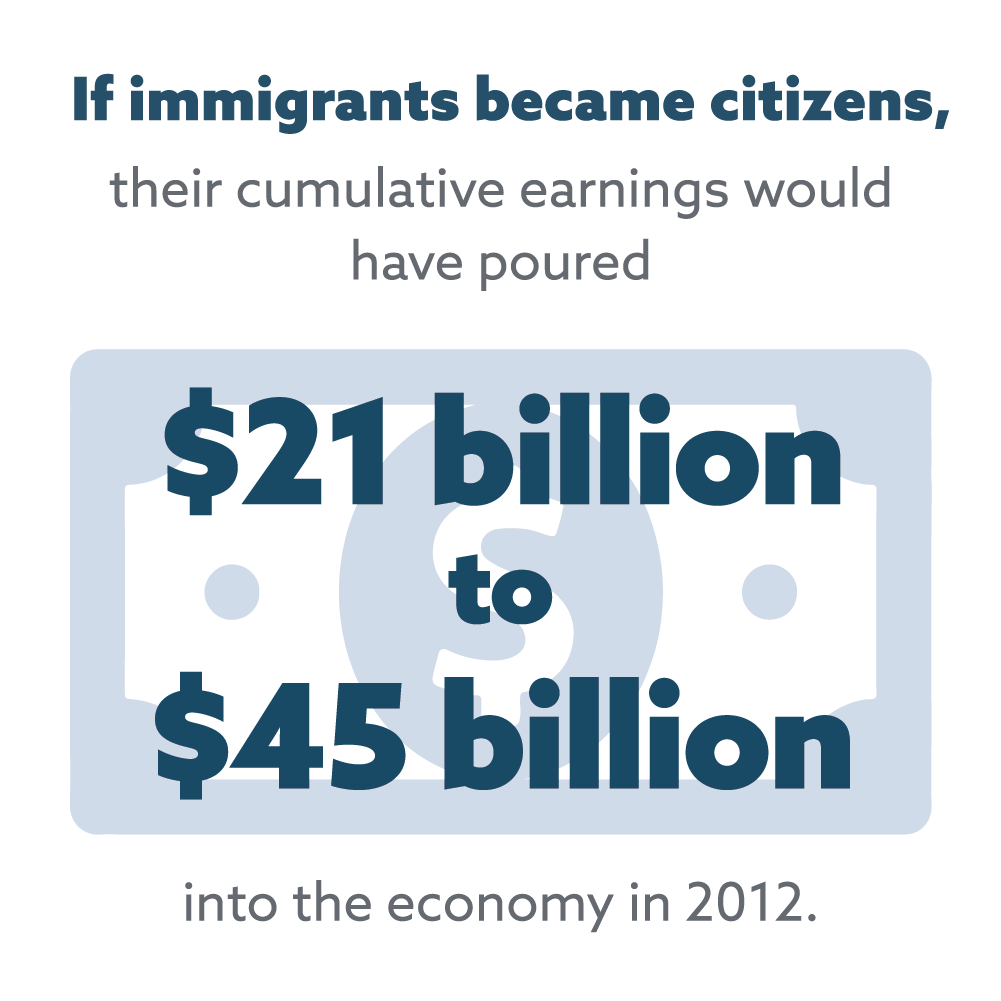

Immigrants who become naturalized citizens see their earnings increase by 8% to 11%, with a gain of a little over 5% in the first two years after they become Americans, according to a 2012 study from Manuel Pastor and Justin Scoggins at the University of Southern California’s Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration. New Americans’ earnings continue to grow in subsequent years, although the rate does slow over time.

The economic benefit extends beyond the individuals and their families to the entire U.S. economy. Pastor and Scoggins estimated that if the immigrants eligible for naturalization in 2012 became citizens, their cumulative earnings would have poured $21 billion to $45 billion into the economy. That’s billions of extra dollars being spent at local businesses, invested in children’s education, and used as a down payments on homes or seed money to start businesses.

Given the joint economic benefit — both to the new citizen and to the U.S. economy — Americans should encourage eligible immigrants to become citizens.

Social Benefits

Perhaps more important than the economic benefits are the social benefits that accrue when immigrants naturalize. Citizenship comes with certain rights and responsibilities that lawful permanent residents do not have, including the right to vote, the opportunity to serve on a jury, and the ability to run for public office. Citizenship allows immigrants to more fully invest in American democracy and our future, strengthening our society. The act of naturalization, after all, is about committing to America and our shared ideals.

Choosing to permanently become an American is not a light decision. Immigrants who wish to become American citizens must have been lawfully present in the U.S. for three to five years, have had a continuous presence in the United States, have a clean criminal record, pass English and civics exams, and pass interviews with USCIS officials.

The oath of citizenship requires new citizens to renounce their allegiance to their home countries. It requires new citizens to commit to defending the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic. In many cases, naturalized citizens must give up certain rights in their home countries. Yet many immigrants continue to judge the benefits of U.S. citizenship as greater than the losses they may incur. They recognize that citizenship is a social and economic equalizer, and they are committed to full participation in the American experience.

Once immigrants become citizens, they are quick to assimilate and integrate in American society. In a 2019 report for The Center for Migration Studies, Donald Kerwin and Robert Warren found that naturalized citizens have similar or higher levels of educational attainment and employment than native-born citizens. New Americans work in skilled professions about as often as those born here, and their income is the same or higher.

They are thriving in America, and citizenship through naturalization simply cements their successful

integration.

BARRIERS TO NATURALIZATION

The steepest barriers to naturalization are often cost and a lack of mastery of the English language. Many immigrants also find it difficult to make the time commitment to go through the naturalization process. To apply for citizenship, immigrants must attend several interviews at a USCIS field office — most likely requiring time off from work. Immigrants also must find the time to study for their citizenship exams — tests of reading, writing, and history — which can be difficult given work schedules and family commitments.

American immigration law is complex, and the stakes are too high for immigrants to forego hiring an attorney to shepherd them through the process. This imposes yet another cost to becoming a citizen. As if the natural barriers to naturalization were not enough, USCIS has recently increased administrative barriers.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) issued a report in 2020 detailing some of the bureaucratic hurdles implemented in recent years, many of which stem from more rigorous vetting to root out fraud. After reviewing survey data from the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, MPI found that USCIS was conducting lengthier interviews — in some cases twice as long as before. USCIS also issued more requests for evidence on applications than usual; administered the civics and English exams more strictly; and, in some cases, asked very detailed questions not related to applicants’ eligibility for citizenship.

At least a quarter of the survey respondents reported that applicants missed interviews because notices were sent too late, to wrong addresses, or to attorneys rather than applicants. We do not know whether these applicants’ citizenship journeys were delayed due to incompetence or due to deliberate administrative chicanery.

These policy changes have done nothing to reduce the rate of acceptance of naturalization applications. As MPI notes in its report, the approval rate has been relatively stable at around 90%. Rigorous vetting is not itself problematic, but it does not benefit anyone when it does not ultimately change the outcome, just delays it.

We all benefit when fully assimilating immigrants. Delaying naturalization delays those benefits.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Immigrants encounter many barriers on the path to citizenship. USCIS should take a hard look at how it administers naturalization and the barriers it puts in place. And our businesses and communities can offer support to make overcoming those barriers more likely.

Encouraging naturalization—USCIS

Given the benefits of citizenship outlined in this paper, it should be in the interest of the U.S. federal government, including USCIS, to find ways to reduce barriers to naturalization.

Keeping naturalization fees reasonable is an excellent first step. As an agency funded almost entirely by the fees it charges for the services it provides, USCIS must raise fees on occasion to continue to fund the agency. But it should only do so with an eye on maintaining the services it provides and should not raise them by more than is necessary. USCIS should also ensure fee waivers continue to exist for those who struggle to afford their citizenship applications. Poorer immigrants are less likely to naturalize, so fee waivers eliminate one of the highest barriers to obtaining citizenship for these immigrants. Finally, the naturalization application procedure and accompanying rules should be evaluated to ensure that increased vetting and limitations on accelerated processing are effective at catching fraud rather than just slowing down naturalization.

Encouraging naturalization—community level

A robust, modern U.S. immigration policy should encourage naturalization for those immigrants eligible for it. This can be facilitated from the ground up, starting with nongovernmental organizations, faith-based organizations, and local communities working with immigrants to help them navigate the steps required to naturalize.

A great example of this work at the community level is programming from the City of Dallas’s Office of Welcoming Communities and Immigrant Affairs (WCIA). Cities like Dallas have little authority when it comes to changing the legal structures of the immigration system, but the Dallas WCIA has constructed a plan to make the Dallas community more welcoming to immigrants.

Among other activities, the WCIA created a citywide citizenship campaign to “promote awareness about the benefits and responsibilities of U.S. citizenship.” The city proactively works with community organizations to offer free naturalization application workshops. City libraries have resources to educate everyone about citizenship and civic engagement. Finally, the city connects immigrants to other residents via volunteer opportunities, in an initiative sure to strengthen the entire community.

Encouraging naturalization—the business community

The business community, too, has a role to play in promoting naturalization. Employers can make naturalization more attainable for eligible immigrants by creating policies that support immigrant employees through the many steps in the process. Applicants must find time to study for the citizenship exam and attend multiple interviews. Once approved, immigrants often must take time off work to take their oaths of citizenship. Employers who can provide flexibility and affirmative encouragement during this process can contribute positively to their employees’ citizenship journey.

Some companies are already taking steps to support their immigrant employees. For example, Walmart not only provides opportunities for its associates to take English language classes, but also partners with the National Immigration Forum to provide access to an online portal that helps associates explore their legal immigration options. This is an excellent example of how employers can use corporate policies to help their immigrant employees integrate faster and thrive in the United States.

CONCLUSION

Naturalization is not just about the immigrants. It is about the contributions and vitality the United States gains each time an immigrant becomes a citizen. It is about the social cohesion we gain when we can eliminate the barriers between immigrants and the native born: We are all equal as American citizens, with an equal voice, equal protection of the laws, and an equal stake in the success of the community.

The United States should make it a priority to encourage immigrants to become Americans. Our policies at all levels of government and across the private sector should encourage eligible immigrants to become naturalized citizens. Immigrants reach their full potential when they become fully integrated into American society. All of us can work together to welcome immigrants and help them become Americans.

1 The Carnegie Corporation of New York is a generous supporter of the Bush Institute’s immigration policy work.