William McKenzie, Senior Editorial Advisor at the Bush Institute, writes about the barriers journalists face in Latin American countries and the importance of independent reporting for a democratic society.

Alfonso Esquivel. Antonio de la Cruz. Armando Lopez. Fredid Roman. Heber Vasquez. Jose Arenas. Juan Lopez. Juan Muniz. Luis Ramirez. Maria Lopez. Roberto Barrera. Sheila Oliveira. Yessenia Falconi.

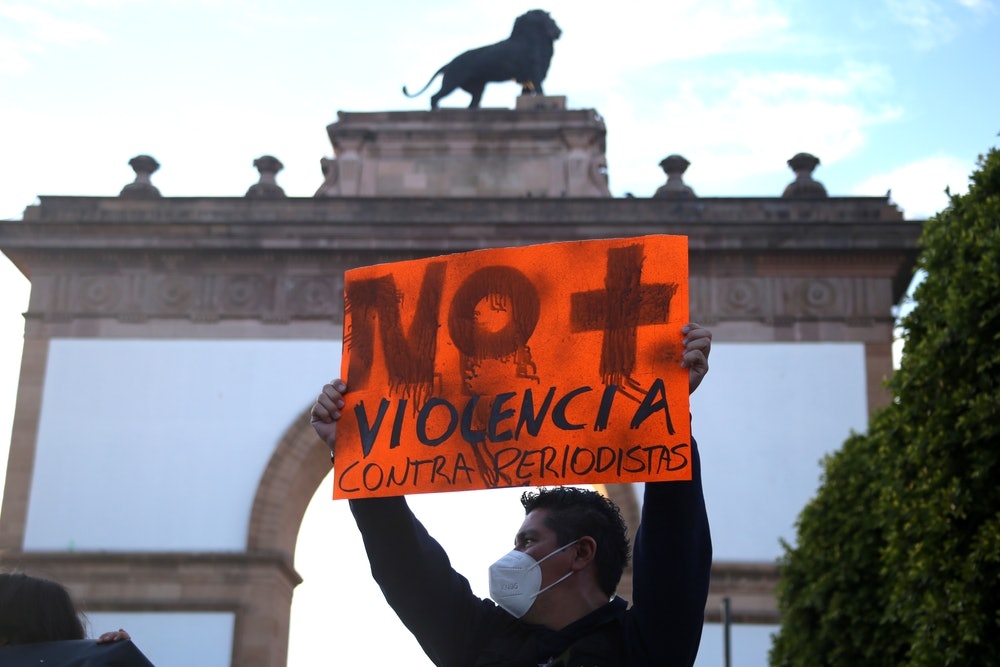

Remember those names. They are the 13 journalists killed in Mexico so far this year. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) confirms that three of those individuals were murdered in their line of work while the organization is still investigating the motive of the other 10 slayings.

No one would be surprised if other journalists found their names on that list over the coming months. According to CPJ, Mexico has turned into the most dangerous country for journalists in the world. Those 13 dead members of the press are the most CPJ has documented in Mexico in a single year. (In late September, the attorney general for the state of Chiapas issued an alert about a journalist gone missing in that southern state.) All for simply trying to provide factual information to readers and viewers about their country.

Serious abusers of independent journalism

Mexico’s drug cartels pose a particular obstacle to independent journalism. Not only are physical threats a reality for some journalists, but the power of the cartels in Mexico’s northern states and along the Pacific Coast can lead to journalists censoring themselves.

That can happen in different but equally disturbing ways. Journalists under pressure may decline to run a story about corruption. Or they may publish a piece the cartels want published, a point that Rice University Political Science Professor Mark P. Jones, the Joseph D. Jamail Chair in Latin American Studies, emphasized in a recent interview.

Unfortunately, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, popularly known as AMLO, has not firmly upheld the importance of a free press in a democracy. Earlier this year, after the slaying of a Mexican journalist, the Inter American Press Association called upon AMLO to curtail his harangues against journalists who criticize his administration. As the press group put it, “such attacks from the top of power encourage violence against the press.”

Mexico’s drug cartels pose a particular obstacle to independent journalism. Not only are physical threats a reality for some journalists, but the power of the cartels in Mexico’s northern states and along the Pacific Coast can lead to journalists censoring themselves.

Mexico is far from the only country in the Americas where journalists face personal and professional barriers. Nicaragua. El Salvador. Honduras. Guatemala. Venezuela. They are among the Latin American nations that the Committee to Protect Journalists considers serious abusers of independent journalism. So does Freedom House, which gives those five countries a score of two or lower on its four-point 2022 ratings for media freedom.

In Nicaragua, longstanding dictator Daniel Ortega suspended 17 radio and TV stations in September. Two months earlier, his government raided the homes of a reporter and a photojournalist working for La Prensa newspaper. The government also detained two drivers working for the independent operation.

The list continues. In June, authorities canceled the legal status of the independent Trinchera de la Noticia. In March, a judge found the publisher of La Prensa guilty of money laundering after a closed-door trial. A month before, another journalist was sentenced to nine years in prison for conspiring to undermine the integrity of the nation and distributing false information.

Honduras is troubling as well. CPJ reported in July that Honduran authorities had pressed criminal charges against a Radio Progresso reporter for covering the eviction of Indigenous people. In June, a camera operator and television host was shot and killed while riding his motorcycle, which press freedom advocates in the country claim was no random act of violence. In March, gunshots were fired at the offices of a radio station that covers national news and events.

Mexico is far from the only country in the Americas where journalists face personal and professional barriers. Nicaragua. El Salvador. Honduras. Guatemala. Venezuela. They are among the Latin American nations that the Committee to Protect Journalists considers serious abusers of independent journalism.

In Guatemala, the government detained prominent journalist Jose Ruben Zamora in July on charges of money laundering and blackmail. At the same time that agents broke into his house to arrest him, other government representatives controlled the offices of El Periodico, the respected independent newspaper Zamora founded, for 16 hours. Moves like those are clearly meant to intimidate, although, as the Latin American Journalism Review explains, Zamora has suffered harassment before.

In 2003, he and his family were held hostage in their home. In 2008, he was kidnapped, drugged, and dumped along a roadside. Guatemalan journalism observers term this latest event part of a “campaign of hunting, harassment, and violence.”

Here’s one more example: The Venezuelan government has teamed up with private sector internet providers to block access to reliable news sites in that country. Last November, for example, private internet service providers blocked 35 news sites during regional elections. The government previously had blocked other independent news sites, along with closing down newspapers and TV and radio stations. These moves undermine the flow of information that reporters trained in independent journalism gather.

Brazil doesn’t rise to the same level of repression. But a reliable flow of information in the largest nation in South America certainly faces pressures. A well-known British journalist and an Indigenous expert were killed this summer while reporting on saving the Amazon. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonoro particularly has chipped away at the idea of journalists holding leaders accountable. Freedom House reports that “Journalists who criticize Bolsonaro face online and offline harassment, and outlets that carry such criticism face economic pressure from the government.”

These are just some of the attempts to control the workings of a free press in parts of Latin America. Increasingly, journalists and media organizations find their ability to provide reliable reporting and in-depth investigations restricted in some countries. The limits being placed on them are part of a larger unraveling of democracy across Latin America.

Responding to the attacks

The question is, what to do about these challenges?

The most important step forward is for Latin American civil society leaders who value a free press to support this fundamental element of an open society. That includes publicly embracing efforts to bolster independent reporting.

Fortunately, a number of efforts exist. During this summer’s Summit of the Americas, the Organization of American States (OAS) helped launch the Center for Media Integrity of the Americas. The Center, which plans on becoming an independent entity, seeks to fight back against pressures on journalists, including from their governments, drug cartels, and corporate interests.

John Feeley, former U.S. Ambassador to Panama, heads the Center, whose founding partners are The Washington Post and the Colombia-based Gabriel Garcia Marquez Foundation. In September, the Center hosted its first conference, featuring exiled journalists from Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua. The reporters told their stories, explained how attacks on freedom of the press are linked to declines in democracy, and advocated for the cause of independent journalism in the Americas.

Efforts like these are important because they emphasize the value of a free press in countries where journalism is under attack. Rosental Alves, a Brazilian journalist who heads the University of Texas at Austin’s Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, contends that people need to know the role of a free press in a democratic society. “We once assumed they knew,” he said. Media organizations especially need to be assertive in educating people about the link between democratic freedom and an independent press.

The most important step forward is for Latin American civil society leaders who value a free press to support this fundamental element of an open society. That includes publicly embracing efforts to bolster independent reporting.

Training journalists is another essential need in the region. Here, too, a number of efforts exist. The Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR) is investing in journalists doing investigative reporting in Latin America. UT-Austin’s Knight Center is equipping future reporters to work in the region. And the Center for Media Integrity in the Americas will host a competition to award selected Latin American journalists money to pursue their reporting projects.

Training journalists requires money, of course. Private philanthropy especially can help provide necessary resources. Government assistance for getting a vibrant press off the ground in democratically challenged nations can only go so far before it looks like governments are spinning stories.

That said, publicly funded operations like Voice of America (VOA) that adhere to journalistic standards serve an important function. VOA’s Spanish language service delivers news across Latin America over various platforms. The coverage can be a vital source of reliable information to viewers and listeners in nations where freedom of expression is under siege.

The United States cannot fix this problem on its own, but our voice matters. The Biden administration rightly acknowledged this spring the need for journalistic freedom. The United States needs to continue to promote this idea, and not just on anniversaries like World Press Freedom Day.

As Alves says, “When you kill a journalist, you also are killing an idea: the right to gather and distribute information.” That is the larger reason democrats around the world should stand against the undermining of a free flow of information. We live in a time when disinformation abounds, often through social media or big microphones. Citizens in every nation, especially those where democracy is on the wane, need access to reliable sources of information and news, the kind that a vibrant free press provides. Without such, democracy cannot take root, much less thrive.