The Role of Foreign Enablers in Perpetuating Taliban Corruption in Afghanistan

About the Series

Captured State is a series of three reports published by the George W. Bush Institute that explores how the Taliban have relied on corrupt and kleptocratic behavior to consolidate power in Afghanistan. The report series examines Taliban corruption, the disproportionate impact on women, girls, and other vulnerable communities, and the role of foreign enablers in perpetuating the Taliban’s kleptocracy to identify new and underutilized policy options to advance peace, stability, and freedom in Afghanistan.

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The international community could have significant leverage over the situation in Afghanistan by denying the Taliban access to resources that power their extremist ambitions and brutal rule. Instead, some external actors are taking advantage of the instability in Afghanistan to further their own strategic interests. This undermines both the hopes of the Afghan people and the efforts of others in the international community to advance peace, stability, and prosperity globally.

Certain foreign governments – led by Iran, China, and Russia – as well as multinational organizations, private sector entities, and financial institutions benefit from turning a blind eye and even participating in the corruption and kleptocracy fueling the Taliban’s grip on power in Afghanistan.

Considering the exorbitant human and geopolitical costs of the Taliban’s corruption, the United States and other members of the international community must take urgent action to disincentivize foreign enablers of the Taliban from lending the group legitimacy or aiding its accumulation of wealth and power.

a. OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

- The United States and the international community should formally designate the Taliban as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) to discourage foreign governments, companies, and financial institutions from conducting business with the Taliban.

- The United States should designate Afghanistan as a Primary Money Laundering Concern under the USA Patriot Act to significantly increase the risk to foreign companies to enter business deals with the Taliban.

- The United States Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), Department of State, Department of Defense, Department of the Treasury, and USAID should harmonize information-sharing practices that enhance transparency and U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.

- The international community should coordinate efforts to invoke human rights and anti-corruption sanctions against Taliban leaders using mechanisms similar to the Global Magnitsky Act.

- The international community needs to take a more definitive role in confronting the Taliban’s ability to exercise corruption, profit from kleptocracy, and carry out human rights abuses.

2

INTRODUCTION

Since the capture of Kabul in August 2021, the global community has consistently condemned the Taliban’s criminal activity and oppression of vulnerable communities across Afghanistan. But this condemnation has in many ways failed to turn into substantive action that meaningfully holds the Taliban accountable for their egregious human rights violations. A dire economic crisis in Afghanistan has at the same time forced the Taliban to expand external relationships to make a profit, enhance influence, and safeguard assets. In conjunction with both eager and accidental facilitators, this has created lifelines – whether intentional or not – for the Islamic emirate’s unrelenting push for global validation.

Opportunistic enablers disregard the Taliban’s vile exploitation of the state and view Afghanistan as a vehicle for their own geopolitical ambitions. By engaging the Taliban as a potential partner, state and nonstate actors have both informally and officially – in a growing number of cases – established an increasingly cooperative relationship that grants the Taliban leverage for their desperate push for legitimacy.

Meanwhile, an expanding number of international institutions have become not only complacent, but increasingly complicit in the Taliban’s corruption and kleptocracy and the direct influence of these actions, leading to widespread human rights abuses.

Keen to find ways to advance their agenda and desire for global recognition, the Taliban have enthusiastically seized on these opportunities, exploiting bilateral, multinational, and private sector engagement, as well as the fragmented coordination among international actors.

To respond appropriately, global leaders must harmonize efforts to counter the Taliban’s campaign for recognition, deploying and enhancing all available mechanisms to hold the Taliban and their enablers to account.

3

WHY THIS MATTERS NOW

In their relentless pursuit of profit and control, the Taliban have unleashed unimaginable abuses on the Afghan people. From the brutal institution of gender apartheid to widespread deprivation, communities across Afghanistan are shouldering horrific levels of misery as the situation deteriorates further.

To their credit, individual countries, nonstate actors, and the international community at large have ostracized the Taliban for their abhorrent actions. Steps taken include a refusal to recognize the Taliban government as the legitimate authority in Afghanistan; U.N. resolutions and unified statements of condemnation; freezing the Taliban’s access to Afghanistan’s central bank assets; and allowing collective travel ban waivers to expire in 2022.

“We see condemnation but very little action.”

– Sima Samar

Former Afghan Minister of Women’s Affairs

Unfortunately, it’s not nearly enough. In the two years and counting since the Taliban returned to power, institutionalized oppression, an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, rampant exploitation, and regional and global security concerns have only continued to grow.

Much of this is due to the Taliban’s ability to bypass existing accountability mechanisms, thanks to their ruthless utilization of corruption and kleptocracy.

But international enablers are also complicit in this theft and entrenchment in power. The preservation and expansion of the Taliban’s status quo is increasingly being influenced by state and nonstate actors outside Afghanistan – whether they’re acting intentionally or not.

In many ways, complacency, indifference, and the prioritization of profit and influence have come at the expense of Afghan lives, especially those of women and children and ethnic and religious minorities. Without action, both human dignity as well as global stability will continue to erode.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Leverage exists – particularly in multilateral spheres of influence like the U.N. Far more can be done to hold the Taliban to account. And governments, intergovernmental organizations, and civil society institutions all bear responsibility.

4

FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS AND STATE-LINKED ENTITIES

Despite general condemnation of the Taliban’s use of violence and repression of women in Afghanistan, a number of countries have chosen to continue engaging with the Taliban. It’s worth noting that for most foreign actors, these relationships are inherently uncomfortable, regardless of regime type. Concern for the security and stability of Afghanistan and the region remains the common denominator among the country’s neighbors, given the potential for armed insurgency, violence, and mass migration to spill across Afghanistan’s borders. But in the calculus of the countries discussed here, the strategic benefits of advancing priority interests and strengthening their own position on the global stage appear to outweigh other costs.

This section will look at three sets of foreign actors relative to their degree of current engagement with the Taliban and influence goals. Ultimately, their engagement appears to be moving toward normalizing relations with the Taliban, regardless of whether formal recognition is ever declared. This risks eroding the effectiveness of two of the most powerful incentives the international community can bring to bear to negotiate a long-term, sustainable peace and opening in Afghanistan – integration into the global economy and diplomatic recognition.

a. OPPORTUNISTIC AUTHORITARIANS

The leaders of Iran, China, and Russia are wary of the Taliban and their ability to guarantee stability in Afghanistan but have at the same time pursued opportunities to advance their own objectives where strategic interests overlap. The regimes in Tehran, Beijing, and Moscow have thus adopted Afghanistan policies that seek to leverage Taliban rule for their own geopolitical ends while managing the risks of Taliban-fueled instability. Iran’s, China’s, and Russia’s strategic goals include cultivating alternative economic opportunities, evading accountability from the international community, and denigrating the integrity of Western market democracies.

“Authoritarian systems have open arms for the Taliban; human rights and women’s rights take a back seat.”

– Nilofar Sakhi

Professional lecturer of international affairs at George Washington University

Iran

The Taliban’s relationship with the Islamic Republic of Iran may ultimately prove to be the most consequential of the three in terms of enabling Taliban corruption and exploiting their control over the Afghan state. Iranian officials and the Taliban met more than 67 times between the resumption of their diplomatic relations in October 2021 and February 2023, according to Aaron Zelin, the Gloria and Ken Levy Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Interactions between the Taliban and Iranian officials surpassed those with any other country in 2023, and Iran allowed the Taliban to take control of Afghanistan’s embassy in Tehran in February 2023, the independent Afghan media outlet Amu TV reported. This is despite historical tensions between Shiite Iran and the Sunni Taliban over the Taliban’s mistreatment of and violence against Afghanistan’s predominantly Shiite Hazara community, conflicts over water rights along the border, Afghan migration to Iran, and narcotics trafficking.

One asset Iran can offer the Taliban is the experience and know-how to reconfigure the Afghan state in ways that serve extremist ideological preferences, extend control over the country’s economic resources, and preserve power.

“The Taliban are looking to Iran as a model for establishing an Islamist bureaucracy,” observed Jason Brodsky, Policy Director of United Against Nuclear Iran, in a conversation with the authors.

While the Taliban are experimenting with administering the state bureaucracy, borrowing from Iran’s model of the state would offer a pathway to institutionalize control through the combined use of force and ideology. It would also simultaneously obscure further moves by Taliban leaders to tighten their hold over Afghanistan’s economy and national resources.

Iran’s governance model is based on the capture of the country’s industries by individuals and parastatal organizations linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and provides many mechanisms for corruption and capture by kleptocrats.

“In practice, there are no private industries in Iran,” Saied Golkar, an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, said in a conversation with the authors. “The IRGC has an open hand to do what they want anywhere in Iran. They control the borders and the ports, and they have their own airport where the regime does not check cargo.”

Iranian businesses have a significant economic footprint in Afghanistan, with the lion’s share of the US$2 billion in trade between the countries flowing from Iran to Afghanistan. In April 2023, Tehran and Kabul announced the creation of a new Iran-Afghanistan Chamber of Commerce to increase relationships between business leaders in both countries.

No doubt one goal of increasing business ties is to maximize trade and commerce. But it also effectively opens the door to opportunities for corruption, money laundering, and even the movement of illicit goods between the countries because of the power structure Iran is facilitating. Iranian businesses generally benefit and are controlled by the country’s ruling elite, and Taliban leaders are increasingly pressuring Afghanistan’s private sector to do its bidding.

Likewise, helping the Taliban establish a governance model in Iran’s image would serve to deepen Tehran’s influence over Kabul. Iran is keen to hedge against armed insurgents crossing its border with Afghanistan. Tehran also wants to incentivize the Taliban to take steps to smooth historically tense relations, such as recognizing Iran’s water rights in contested areas near the border. It would also facilitate the ability of Iran’s kleptocratic elites to extend their own enterprises into Afghanistan by creating an alternative space through which they can evade the international community’s sanctions regime and reach different international markets. This would benefit both the Taliban and Iranian leaders.

Despite tension over migration from Afghanistan, Iran has exploited the Afghan migrant population, especially from among the Hazaras it has historically sought to protect from discrimination and violence, including by the Taliban. Researchers at the United States Institute of Peace have documented how Iran recruited tens of thousands of Afghan Hazara migrants to fight in Syria with the Fatemiyoun Division of the IRGC Quds Force, ultimately to the benefit of Syrian dictator Bashar Assad’s government.

“Iran doesn’t care at all about the safety and security of the Hazara minority in Afghanistan,” Kasra Aarabi, Director of IRGC Research at United Against Nuclear Iran, said in a conversation with the authors. “Iran benefits from Hazara migration because it can enroll them in radicalization programs in Iran and employ them in militias.”

Iran could eventually seek to deploy Fatemiyoun militia fighters to western Afghanistan, potentially with Taliban support, to mitigate threats from the Islamic State group’s Afghanistan affiliate, ISIS-K, Arabi theorized. The IRGC Fatemiyoun Division – along with Iran’s Mahan Air, which resumed flights to Afghanistan after the Taliban captured power in 2021 – has been sanctioned by the U.S. Department of Treasury since 2019.

China

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has generally demonstrated a willingness to engage with most any political actor around the world that finds itself in a position of power – particularly when its leaders believe the CCP’s interests can be advanced. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan is no exception, despite general distrust of the Taliban’s ability to maintain security and control in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s wealth of undeveloped natural resources is attractive to China’s long-term economic and strategic ambitions. But China’s leadership appears more interested in helping its state-owned firms and other Chinese businesses lock up access rights and preemptively exclude other competitors than making significant investments that would develop large-scale extractive industries in the country in the near-term.

To build rapport with the Taliban, China has dangled the carrot of connecting Afghanistan to its flagship foreign policy project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as an extension of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Taliban leaders were invited to the Belt and Road Forum marking the 10th anniversary of the global project, held in Beijing in October 2023. China’s leadership has invested significant economic resources in the CPEC and other BRI-linked projects in the region. This has heightened Beijing’s concern that instability and potential spillover violence from Afghanistan could harm the survival and growth of China’s regional economic projects, according to an analysis of regional dynamics by Nilofar Sakhi, a professorial lecturer at George Washington University.

China has maintained its embassy in Kabul and even appointed a new ambassador in September 2023, making it the only country to do so among those that maintain a diplomatic mission in Afghanistan. Then China became the first country to accept a credentialed Taliban-appointed ambassador to an Afghanistan embassy in December 2023, a move that was reconfirmed in January 2024 when Xi Jinping, China’s paramount leader, personally accepted his credentials alongside those of more than 40 other foreign ambassadors in a formal ceremony. A spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry avoided answering a direct question about whether this constituted Beijing’s formal recognition of the Taliban but told journalists at a briefing that “China believes that Afghanistan should not be excluded from the international community,” Voice of America reported.

The exchange of ambassadors represents an important step forward in Beijing’s engagement with the Taliban. It was particularly noteworthy since China urged its citizens to leave the country just a year earlier, when ISIS-K attacked a Kabul hotel frequented by Chinese businesspeople in December 2022.

For China’s leadership, a relationship with the de facto authorities in Afghanistan provides valuable material it can leverage in propaganda for audiences at home and in other parts of the developing world as it seeks to juxtapose itself as a rising global power against a retreating United States and inward-looking West.

This requires managing the narrative about China’s involvement in Afghanistan over the past two decades. China’s assistance to Afghanistan was relatively limited between 2001 and 2021 and always distributed piecemeal with specific demands attached, according to Sayed Mahdi Munadi, a former Afghan diplomat in Beijing who is a faculty lecturer at Sciences Po, in a conversation with the authors.

More recently, Chinese firms have announced deals negotiated with the Taliban, but thus far have been slow to follow up with action. Security risks and the underdevelopment of Afghanistan’s infrastructure remain major impediments to the success of large-scale projects.

“China is afraid of starting projects in Afghanistan because of the optics of having to roll them back after putting people and resources on the ground,” Niva Yau, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, said in a conversation with the authors.

Nevertheless, the pursuit of economic agreements, mining rights, and other licenses by Chinese firms in Afghanistan has effectively meant that a certain amount of corruption that directly benefits the Taliban is already underway, as the authors described in the first paper in this series.

“China has a bribery budget to secure projects outside the country,” former Afghan diplomat Sayed Mahdi Munadi said in a conversation with the authors. “It is seen as a cost of doing business…. There were lots of bribes exchanged in the Aynak copper mining deal,” he added, referring to a controversial US$3 billion 30-year lease granted to a Chinese mining firm in 2008 and which remains stalled.

Among deals proposed between Chinese firms and the Taliban, the Chinese technology firm Huawei allegedly agreed verbally to upgrade Afghanistan’s public security surveillance camera infrastructure in Kabul and other major cities, Bloomberg reported in August 2023. While details around the meeting between the Taliban and Huawei remain sparse, previous agreements between Huawei and illiberal regimes in Ecuador and Uganda resulted in an enhanced ability of those governments to monitor and intimidate members of nongovernmental organizations and opposition political parties.

Ethnic Uyghurs who have resettled in Afghanistan have voiced fears that they will be unduly targeted by this type of surveillance system. Huawei and other Chinese technology firms have helped build a mass surveillance state that has fueled Beijing’s repression of Muslim-majority Uyghurs in China’s northwest Xinjiang region – officially the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Foremost among the CCP’s security priorities in Afghanistan is preventing members of ideological extremist groups from crossing the small border the two countries share between Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor and Xinjiang. Namely, Beijing remains concerned that the Taliban will provide a safe haven to the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which it has accused of fomenting violent separatism in Xinjiang and cited as justification for mass repression of the Uyghur population. In 2020, the U.S. government delisted ETIM as a terrorist organization over lack of evidence about the group’s continued existence and capacity.

Russia

Thirty-five years after the Soviet Union withdrew its troops from Afghanistan, Russia’s influence in the country remains relatively limited compared with other international actors. But like Iran and China, Russia has identified strategic benefits to cultivating a relationship with the Taliban. This has taken place despite the fact that the Taliban have been officially designated a “terrorist organization” by Moscow since 2003.

The Kremlin has leveraged a series of five Moscow Format Consultations since 2017 to put Russia’s core interests at the center of conversations with other key regional players about stabilizing Afghanistan. These include China, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Russia invited the Taliban to two of the three convenings that occurred after they recaptured power in Afghanistan. At the series’ third consultation in 2021, which Taliban representatives attended, the participating countries stressed that they saw the Taliban as the new authorities of Afghanistan and expressed support for unfreezing assets belonging to Afghanistan’s central bank, despite withholding formal recognition. Taliban representatives weren’t invited to the fourth convening in 2022 but did participate in the fifth consultation in September 2023. This was at Russia’s expense and a move that included supporting a request for a travel ban exemption from the U.N. Security Council so that the Taliban’s sanctioned Foreign Minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, could participate in person.

In public statements, Moscow has signaled it is willing to set a lower bar than most other members of the international community for formally recognizing the Taliban as the leaders of Afghanistan’s government. In June 2022, Russia’s Special Envoy to Afghanistan Zamir Kabulov called only for the Taliban to form an “inclusive ethnopolitical government” as a key step toward recognition and stated that the Russian Federation would make a decision without accounting for the “opinion” of the United States or other countries.

Although contact with Taliban members is officially punishable by law because of the Taliban’s designation as a terrorist organization, Russian authorities appear willing to suspend enforcement to increase their own influence and diversify their global economic trade portfolio. It is advantageous for the Kremlin to maintain access to countries unconcerned about the international sanctions regime against Russia for its war of aggression in Ukraine.

To date, however, trade between the two countries remains relatively limited. Russia signed an agreement in 2022 to sell fuel, natural gas, and wheat to Afghanistan. Analysts interviewed by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) thought the deal might serve as a first step to subsequent trade arrangements if both sides could fulfill their commitments.

Although it remains to be seen whether Russia and the Taliban will deepen economic ties or use each other to evade sanctions, both the Kremlin and the Taliban share a keen interest in undermining the integrity of the United States and other Western countries who challenge their own legitimacy.

As it has done in many other regions of the world, Russia’s state media are active in Afghanistan through a Dari-language Sputnik radio broadcast service tailored to Afghan media consumers. While more systematic analysis is called for to assess the potential reach, degree of influence, and impact of Moscow’s messaging through Sputnik Dari, it’s worth noting that radio is the primary form of media consumed by Afghans. While about 50% of all Afghan media outlets were shuttered after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, the station continues broadcasting into the country and had an established social media presence, with more than 322,000 followers on its Facebook page by December 2023. As the Taliban are also exploring how to engage in their own digital messaging and disinformation strategies, they may leverage and amplify the Kremlin’s state-backed narratives. They could even seek training and support from Moscow in building their own network of inauthentic accounts that can manipulate the digital environment.

b. MANEUVERING MEDIATORS

Regional power players Qatar, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Turkey are leveraging the Taliban’s unrecognized status to jockey for position as interlocutors and mediators between the West and the Taliban. Serving in such roles gives these

governments the opportunity to build their own independent global profiles. It also allows them to benefit economically from simultaneous ties with international pariahs without sacrificing access to the wider international marketplace. To this end, all three have maintained their diplomatic missions in Kabul and have accepted Taliban-appointed representatives at Afghanistan’s embassies in their own countries. They have done so despite misgivings about the Taliban’s capacity to guarantee stability in Afghanistan and after condemning the Taliban’s ban on women’s education.

“The Taliban is not an indigenous movement and should never be taken as an indigenous political movement of Afghanistan. It is a regional project, and over time it has been used and abused by various other regional players.”

– Mahmoud Saikal

Former Permanent Representative of Afghanistan to the United Nations

Qatar

Qatar has been the most successful at leveraging its diverse diplomatic ties to brand itself as an effective mediator for conflicts in its geographic periphery. This approach effectively functions as a reputation management strategy to deflect the international community’s attention from the tight control the dynastic government of Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani maintains over Qatar’s political system and civil liberties. The country consistently receives a “not free” rating from Freedom House.

Doha’s role as host to dialogue between the West and the Taliban has cemented Qatar’s diplomatic reputation, although facilitating talks with the Taliban wasn’t the first time Qatar served as an international intermediary. Qatar allowed the Taliban to open a diplomatic office in Doha in 2013 through a negotiated process so that the Afghan and U.S. governments could engage in dialogue with the group. Qatar’s role remained central over subsequent years, hosting the series of meetings that eventually led in 2020 to the eponymous Doha Agreement. This document became the stated basis for the withdrawal of U.S. and other international forces from Afghanistan in 2021. After that, Doha continued to serve as a host to meetings between the Taliban, the U.S., and other foreign diplomatic representatives who don’t officially recognize the Taliban government in Afghanistan.

Qatar’s leaders would like to be recognized for intervening in conflicts to facilitate difficult dialogues, supporting humanitarian causes, and negotiating the release of hostages, including during the Israel-Hamas war. However, they should also carefully weigh whether continuing to hold the door open for the Taliban has had the opposite of the intended effect, given the group’s failings in upholding commitments made in the Doha Agreement.

In the years that Doha welcomed senior Taliban leaders – allowing them to establish residences – some discovered opportunities to grow their wealth and enjoyed relatively lavish lifestyles, despite purported monitoring of their finances. An investigation by the U.K. media outlet The Telegraph in 2022 detailed how Taliban leaders living in Doha during the previous decade had used money from US$10,000 monthly stipends funded by the Qatari government to purchase heavy equipment and set up construction companies that provided services to build stadiums for the 2022 World Cup in Doha.

Several Taliban leaders have continued sending their daughters to Qatar for school at the same time that Afghan girls and women have been denied education – behavior that suggests these Taliban leaders likely also have sufficient finances available to them in Qatar to support maintaining a household and covering school fees there.

UAE

The UAE was a favored destination for Afghanistan’s elite during the years of the republic and provided a refuge to many, including former President Ashraf Ghani, after the country fell to the Taliban in 2021. Afghan businesspeople had looked to the property market in Dubai as a relatively secure location to invest savings from the earliest days when the U.S. government began raising the prospect of withdrawing from Afghanistan. Allegedly corrupt Afghan government officials among them also joined, reportedly purchasing luxury properties in Dubai’s most exclusive neighborhoods.

Senior Taliban leaders were also reported to enjoy access to the UAE during this time. For example, the Taliban’s supreme leader from 2015 to 2016, Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansour, maintained a residence and investments in Dubai, where he traveled frequently from another home in Pakistan, the New York Times reported.

Regional rivalry between the UAE and Qatar incentivizes the Emirates to maintain a relationship with the Taliban to buttress its own position against Qatar. For the Taliban, deepening ties with the UAE provides an opportunity to diversify its own foreign relationships, which it can use as a bargaining chip to negotiate more favorable relationships with other partners.

One such example was the unexpected decision by the Taliban – after they had spent time negotiating a joint operation agreement by Qatar and Turkey – to award an Emirati firm a license to provide ground services for Afghanistan’s international airports in Kabul, Herat, and Kandahar. According to the independent digital media organization Middle East Eye, one reason the UAE company gained an advantage was that it was apparently willing to allow funds it would invest in the operation to be directed through a bank account under Taliban control.

While details remain sparse about the extent to which Taliban leaders may be hiding personal financial resources abroad, financial institutions in the UAE and Turkey have reportedly laundered funds for the Taliban (see Financial Sector). Both have been designated on the “Grey List” of the intergovernmental organization the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) as jurisdictions under increased monitoring for lax enforcement and “strategic deficiencies in their regimes to counter money laundering, terrorist financing, and proliferation financing,” although the UAE was removed from the Grey List in February 2024.

Turkey

Turkey has sought to position itself as a bridge between the Taliban and the West – despite being a member of NATO and a candidate for EU membership – as part of its strategy to be viewed not only as a regional broker, but as a global power.

Ankara also has a strong interest in seeing the Taliban formally recognized as Afghanistan’s government because it wants to stabilize and maximize opportunities for Turkish businesses in Afghanistan without jeopardizing their ability to conduct business with the West.

“As soon as a semi-reputable government recognizes the Taliban, Turkey will jump to recognize them, too,” Richard Kraemer, President of the U.S.-Europe Alliance, said in a conversation with the authors.

Ankara sees a prime opportunity for its construction firms in Afghanistan. They possess expertise suited to Afghanistan’s challenging and earthquake-prone terrain – and can construct infrastructure and other building projects in underdeveloped areas. Turkish officials positively viewed the decision by the Taliban to honor a contract the Ghani government signed with a Turkish firm, allowing it to complete the second phase of constructing the Kajaki hydroelectric dam in Helmand province.

Beyond Turkey’s business interests, Ankara has advocated for greater flexibility toward the international community’s treatment of Afghanistan’s foreign currency reserves, arguing that they should be made available to help the Taliban pay salaries to government employees. As described in our first paper in this series, the Taliban have over time gradually leveraged control over the Afghan state to replace qualified bureaucrats with their own fighters and loyalists. Permitting such a move would have the effect of funneling Afghanistan’s sovereign assets into the pockets of a greater number of Taliban who have joined the state’s payroll.

Turkey has also become an apparent favored destination for senior Taliban leaders seeking treatment for medical conditions. The U.N. Security Council (UNSC) Committee – which has oversight of the international organization’s sanctions regime against listed Taliban members under Resolution 1988 (the 1988 Committee) – granted four designated Taliban leaders with acting ministerial roles travel ban and temporary asset freeze exemptions to go to Turkey for medical care between September and December 2023 alone. At the time, the committee was chaired by Ecuador, with Russia and the UAE acting as vice chairs.

c. NEXT-DOOR NEIGHBORS

Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan represent the third group of state actors positioned to enable Taliban corruption. All three share a geographic border with Afghanistan and, partially due to their proximity, choose to engage with the Taliban.

Pakistan

Pakistan and the Taliban have a long but fraught history that has been further shaken up since the Taliban recaptured Kabul. Pakistan’s military and intelligence services have served as the Taliban’s chief supporters for nearly three decades. However, the Taliban’s protection of the Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP, also known as the Pakistani Taliban) has driven a wedge that has significantly raised the cost of the relationship for Pakistan’s military. The TTP has launched a number of deadly attacks in Pakistan since late 2022 after a ceasefire with Pakistan broke down. While Taliban leadership promised that it would not condone its fighters joining other jihadist groups, indoctrinated Taliban fighters dissatisfied with bureaucratic roles have joined the TTP to fight in Pakistan, according to the New York Times.

Despite this divergence of security interests, the Taliban’s relationships in Pakistan run deep. In particular, the Haqqani network – a faction of the Taliban that maintains close links with al-Qaida and even some members of ISIS-K – has long enjoyed backing and protection from Pakistan’s military intelligence agency. Sirajuddin Haqqani, who wears dual hats as leader of the Haqqani network and the Taliban’s acting Interior Minister, had been issued a five-year Pakistani passport, purportedly at the request of a military intelligence officer. The Pakistani passport enabled him to travel to Qatar during the negotiations that led to the Doha Agreement, in addition to other countries.

Several well-established trafficking networks involving the Taliban also run through Pakistan, benefitting actors on both sides of the border. The Taliban – and now also ISIS-K – have long profited from illegal timber trafficking from Kunar and Nuristan provinces near Afghanistan’s border with Pakistan. An uptick in the trafficking of small arms and military equipment across the border has also been observed by Afghan Peace Watch and the Small Arms Survey. Some of these weapons are likely being diverted to Kashmir; U.S. weapons believed to have come from Afghanistan have been reported in the conflict there.

Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan

Though not necessarily driven by great power ambitions, Uzbekistan’s and Turkmenistan’s interests in maintaining cross-border economic trade and preventing the spillover of violence or migration from Afghanistan put them at risk of becoming enablers of Taliban corruption.

Turkmenistan’s typically reclusive authoritarian regime has welcomed Taliban leaders in Ashgabat on several occasions, including before and after they recaptured Afghanistan in 2021. Of particular interest to Turkmenistan is the construction of a Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline to move Turkmenistan’s abundant natural gas to more distant markets. Turkmenistan and Pakistan signed a preliminary agreement with the Taliban in June 2023. A Eurasianet analysis of a June 2023 U.N. report drew attention to a struggle playing out among Taliban factions and leaders seeking to benefit financially from such a deal, with particular interest from the Taliban’s acting Interior Minister Haqqani.

Uzbekistan’s secular government was initially cautious of the Taliban’s return after the withdrawal

of international forces. But during the Tashkent Conference that Uzbekistan hosted to convene regional powers and the United States in July 2022, Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev said “the international community can and should avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1990s,” when the international community locked the Taliban out. Instead, he called for establishing “friendly relations with neighboring states and mutually advantageous cooperation with the international community,” with an emphasis on improving Afghanistan’s socioeconomic situation.

In a sign of deepening economic ties between the countries, a delegation of Uzbekistan government ministers to Kabul signed a series of export-import contracts valued at US$1.2 billion in November 2023. A business forum to facilitate private sector connections between countries was also held simultaneously in Kabul.

Tashkent is keen to see two other major economic connectivity projects develop after stalling: The first is the Trans-Afghan Railway that would connect the Uzbek city of Termez to Peshawar, Pakistan, through five Afghan provinces. The second is a new 500 kilovolt electricity transmission line to sell power to Kabul and other Afghan provinces. Renewing and making progress on these initiatives will require further engagement from Tashkent with the Taliban.

5

MULTINATIONAL ENABLERS

Though multinational institutions have prominently responded to Afghanistan’s haunting humanitarian crisis and have condemned the Taliban’s egregious human rights abuses, their lack of action in other ways has had consequential impact.

Complacency and complicity within international systems, including those that have vocally condemned the Taliban’s actions, have helped expand the Taliban’s ability to profit from human suffering.

a. LIMITATIONS, LENIENCY, AND LOOPHOLES

Though targeted sanctions against Taliban leaders have existed for well over two decades at national and intergovernmental levels, loopholes, limited updates, and lax enforcement have undermined their intended impact.

This has meant that a number of prominent Taliban leaders – acting cabinet ministers included – have not been subject to the full scope of available financial and travel penalties, especially at the U.N. level.

Perhaps the most prominent of many possible examples is the European adventure of Abdul Bari Omar, head of the Food and Medicine Authority under the Taliban.

Omar traveled to The Hague, the Netherlands, in November 2023 as a representative of the Taliban at the Second World Local Production Forum, a World Health Organization event. He claims he was issued an invitation and a Schengen visa, which allows the bearer to travel to 27 European countries. While there, he was even photographed with Dutch Health Minister Ernst Kuipers (who has since apologized for the incident).

Omar extended his journey beyond the Netherlands, stopping in at least three additional EU countries (Germany, Belgium, and Slovakia). These visits were highly lauded on social media by Omar and other senior Taliban leaders, stressing an emphasis on engagement with various “Afghan ambassadors and diplomats.” They also included a highly controversial stop in Cologne, Germany, for a speech at a mosque. German and Dutch officials have promised a full investigation into the matter.

While more information is important, one key detail is already known: Abdul Bari Omar isn’t on the existing U.N. sanctions list, and neither are the vast majority of Taliban ministers and senior leaders. But even for those listed, lax enforcement of penalties has enabled Taliban officials to bypass travel bans for both personal and official reasons.

The UNSC 1988 Committee granted travel ban exemptions to sanctioned Taliban leaders at least six times between September and October 2023 alone. Half of these were directly related to official attendance at regional convenings in countries like Uzbekistan, China, and Russia. In the cases of China and Russia, the host countries covered the full costs associated with Taliban participation.

Additionally, sanctioned Taliban leaders were granted travel ban exemptions for the purposes of accessing medical care in Turkey in at least four instances between September and December 2023. Many of these cases also permitted asset freeze exemptions, allowing the Talibs the legal ability to access their personal finances and other resources held in Turkey during their trips to Ankara and Istanbul.

These cases, and many others like them, are incredibly cruel failings by the international community (and the UNSC in particular), especially since millions of Afghan women and children largely lack in-country access to even the most basic medical care.

b. UNINTENDED LEGITIMACY

The global community’s inconsistent treatment of the Taliban – despite formally denying them recognition as the legitimate rulers of Afghanistan – has diluted international solidarity and enabled Taliban corruption, propaganda, and subsequent human rights abuses. So have inadvertent endorsements and misguided actions.

Too many delegations meeting with Taliban officials from governments, intergovernmental organizations, nonprofits, and civil society institutions are all male. When female officials have participated, including at meetings hosted outside Afghanistan and other Muslim-majority countries, many have elected to wear headscarves when in discussion with Taliban leaders. These actions unintentionally validate the Taliban’s deplorable subjugation of Afghan women and girls.

Despite existing sanctions, Taliban leaders have been hosted via private jets and upscale accommodations when invited to participate in international dialogues on topics like “peace,” “human rights,” and “diplomacy.” Not surprisingly, attending Taliban leaders have gleefully manipulated these opportunities and their associated images for propaganda purposes, including falsely projecting their participation as “a step to legitimize (the) Afghan government,” as one Taliban delegate in 2022 talks hosted by Norway told the Associated Press.

Civil society organizations are also at fault. For example, many international sporting bodies – like the International Editor-in-Chief, Zan Times

Olympic Committee – have yet to expel the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan despite its use of gender apartheid, including a ban on women’s sports. Multiple threats have been made, but the IOC and others have yet to formally act.

“The Taliban exploit relationships…. The global community is not thinking long term…. `Is this logical?’ is never considered.”

– Zahr Nader

Editor-in-Chief, Zan Times

Institutions like the international soccer governing body FIFA and the International Cricket Council have also so far ignored pleas for recognition from displaced female Afghan athletes. At the same time, they have continued their official association with Afghanistan’s sport governing bodies, regardless of Taliban rule.

Though some regional and global competitions have allowed displaced female athletes to compete, many have lent perhaps unintended legitimacy to the Taliban by also permitting the Islamic emirate to field a male-only team as a recognized and participating entity.

Most alarming, Taliban leaders are increasingly appearing at regional conferences and other member-based convenings. While some of this has been due to supposed confusion – like the November 2023 incident at The Hague – other examples abound. These include but are not limited to events hosted by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and, as previously mentioned, the 2023 Moscow Format Consultations and China’s Belt and Road Forum.

In many of these instances, travel required the approval and a travel ban exemption from the UNSC 1988 Committee. While these events’ host countries have maintained that the Taliban aren’t a recognized authority and, in some cases (like Russia), have listed the group as a banned terrorist organization, including senior Taliban leaders alongside regional and international counterparts sends a dangerous message. This is especially true as, in many cases, Afghan civil society leaders remain absent from the most meaningful elements of these discussions.

c. LACK OF ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS

Humanitarian assistance remains a vital lifeline for vulnerable communities across Afghanistan. No one is more in need of access to these essential goods and services than Afghan women and children.

However, as explored in the prior two papers in this series, the Taliban have wasted no time in infiltrating and exploiting humanitarian resources. And multinational institutions have had a hand in enabling this abuse through the lack of comprehensive accountability mechanisms.

Lack of data and monitoring processes and waning cooperation between stakeholders in the distribution of aid plays a considerable role in intensifying the already challenging environment for transparency in Afghanistan.

Since the international withdrawal, the Taliban have enacted more than 100 “official” directives to exert control over humanitarian aid flows, according to John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR). Not surprisingly, Taliban interference in aid distribution rose throughout 2023, including a significant increase in instances of harassment, violence, and detention perpetrated against humanitarian workers.

While support for the most vulnerable populations in Afghanistan is imperative, adherence to Taliban demands is undercutting mechanisms for accountability and ultimately critical access to assistance.

“The Taliban continue to manipulate the situation.”

– Habib Khan

Founder, Afghan Peace Watch

As the custodians of the largest single country humanitarian aid appeal ever launched, the United Nations and contributing donor countries must do more to document and minimize the Taliban’s ability to divert humanitarian assistance in Afghanistan.

d. AN UNCOORDINATED APPROACH

International stakeholders have largely been unanimous in their condemnation of the Taliban’s abhorrent brutality. But notable coordination gaps have prevented words from being put into action, undermining multilateral efforts to hold the Taliban to account. Inevitably, this awkwardness has allowed the Taliban to continue to profit from state resources and the suffering of the Afghan people.

For example, though nearly three dozen countries have comparable laws targeting perpetrators of corruption and egregious violations of human rights, there has yet to be a coordinated approach to utilize these levers of accountability against Taliban leadership.

Moreover, confounding and conflicting messages from national, regional, and international leaders regarding Taliban recognition on the world stage have further enabled Taliban propaganda and their pursuit of international legitimacy.

6

FINANCIAL SECTOR

Afghanistan’s economic crisis makes it challenging for the financial sector to develop reliable banking services critical to storing and moving funds. Hindered by a lack of institutional capacity and experts, Afghanistan’s financial institutions continue to spiral with little international connectivity. This prevents them from accessing international banks and stable economies.

Afghanistan’s domestic economic troubles will continue to constrict banking channel expansion, likely increasing foreign institutions’ reluctance to enter Afghanistan’s business environment in the short term. As more international banks look to completely disengage from Afghanistan’s financial instability, the country will likely continue to be a physical cash-dependent economy with little liquidity and access to funds.

“Anything that the Taliban touches should be treated like we treat North Korea.”

– Juan C. Zarate

Chairman and Co-Founder, Foundation for Defense of Democracy’s Center on Economic and Financial Power

The dismal outlook for Afghanistan’s banking sector makes it unattractive even for Taliban leaders, incentivizing them to go elsewhere to store or move their finances securely. Western governments’ lack of clarity on sanctions policy makes things worse, causing international financial institutions to mostly de-risk and avoid doing business with Afghanistan to protect against possible violations.

To mitigate their lack of banking options, the Taliban often look to neighboring countries and their financial institutions to house their assets. This allows the Taliban to protect ill-gotten finances in internationally linked banks, facilitating the movement of money easily through the global financial system.

The Taliban have historically looked to states in South Asia and the Middle East to access global financial markets, reap the benefits of their corrupt activity, and use their ill-gotten gains without restrictions. That’s because places like the UAE, Turkey, and Pakistan generally have stronger economies, robust regulations and enforcement, and enough political stability to allow international banks to operate freely within the regions. With nearby access to globally linked financial institutions, the Taliban have open entry to Western economies and markets.

Taliban leaders have also become adept at obscuring the source of their illicit and corrupt finances by creating networks of front companies that hide any connections to illegal activity and the Taliban. Due to the cash-intensive nature of the Afghan economy, the Taliban employ the façade of legitimacy by using front companies to move cash surpluses out of the country. By creating companies in sectors that are transaction intensive and which use several supply chains, such as import-export and construction businesses, the Taliban can deposit their finances into business accounts and move the money freely between countries. Such tactics exploit loopholes in existing sanctions policies, which only forbid financial institutions from doing business with the Taliban and known affiliates, not Afghans.

By using Afghans and affiliates that have no apparent direct links to them, the Taliban can access financial institutions, which are only required to collect documentation and screenings on potential clients. Loopholes such as these complicate banks’ ability to screen out corrupt or nefarious organizations. Likewise, when front companies operate under an individual with no transparent connections to the Taliban, financial institutions can contribute to the Taliban’s activities unknowingly.

Such tactics were in use before the 2000s, when the Haqqani network, a subgroup within the Taliban, established relationships with financial institutions in the UAE to launder their illicit proceeds with little scrutiny. The system, consisting of a web of trusted business proxies and front companies, remains in place decades later. Similarly, the Taliban leveraged the help of professional money launderers throughout the 2000s and 2010s to smuggle gold and deposit their money into financial institutions based in Dubai. Though the UAE publicly blacklisted the Taliban in 2014 and has supported the United States and other countries in investigations, financial relationships with UAE banks have likely shifted to covert ones. Likewise, the use of front companies and proxies complicates the ability of financial institutions to determine if the relationship is connected to the Taliban.

Turkey’s financial sector has also become a haven for Taliban funds, as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists determined in their FinCEN Files exposé in 2020. Over 500 transactions worth more than US$35 million were conducted without information on the companies associated with the transactions, signaling potential money laundering cases, the report showed. Aktif Bank, an investment firm in Turkey, completed transactions for Watan Oil and Gas, a subsidiary of Afghanistan’s Watan Group, after the company had paid millions of dollars to the Taliban for protection. Such cases occur in tandem with money laundering friendly policies passed by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. These include “wealth amnesty” decrees permitting offshore finances to enter Turkish banks with no inquiry or scrutiny during established windows of time.

Though the Taliban have been able to take advantage of existing deficiencies in the financial sector in countries proximate to Afghanistan’s borders, opportunities exist for the terrorist group to access international markets through domestic institutions. For example, Bank Alfalah, one of the largest banks in Pakistan, has a presence in central Asia and the Middle East. In Afghanistan, the Taliban could use Bank Alfalah, which has a correspondent relationship with Citibank granting it international access, to move money freely under the cover of a network of front companies. Likewise, using non-Western currencies for international business deals could help the Taliban evade supervision from sanctioning countries. Due to the secretive nature of the financial system, privacy banking laws, and an insufficient understanding of the Taliban’s financial network, the Taliban could employ a host of unmapped intermediaries that conduct business on their behalf. Among these are Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) and Taliban Relatives and Close Associates (RCAs). These are people who are in or have close connections to political circles and who can be entrusted with ill-gotten financial assets as front people to hide the funds’ original source.

7

PRIVATE SECTOR

Afghanistan’s economy and degraded rule of law under the Taliban will likely hamper the development of its private sector. Bridled by a lack of critical banking services and access to cross-border transactions, companies will continue to be constrained by the lack of financial services necessary to operate successfully. Though the Taliban have positioned themselves at the top of all ministries, they have been negligent in directing resources to the development of the private sector due to their self interest and exploitation of power. Afghanistan’s lack of sustainable development prevents domestic companies and business owners from operating at maximum capacity. This provides opportunities, despite sanctions, for foreign companies to do business in the country’s key sectors, such as agribusiness and natural resource extraction. Due to constraints on Afghan companies, the Taliban are outsourcing contracts to foreign companies that allow them to exploit economic opportunities for themselves.

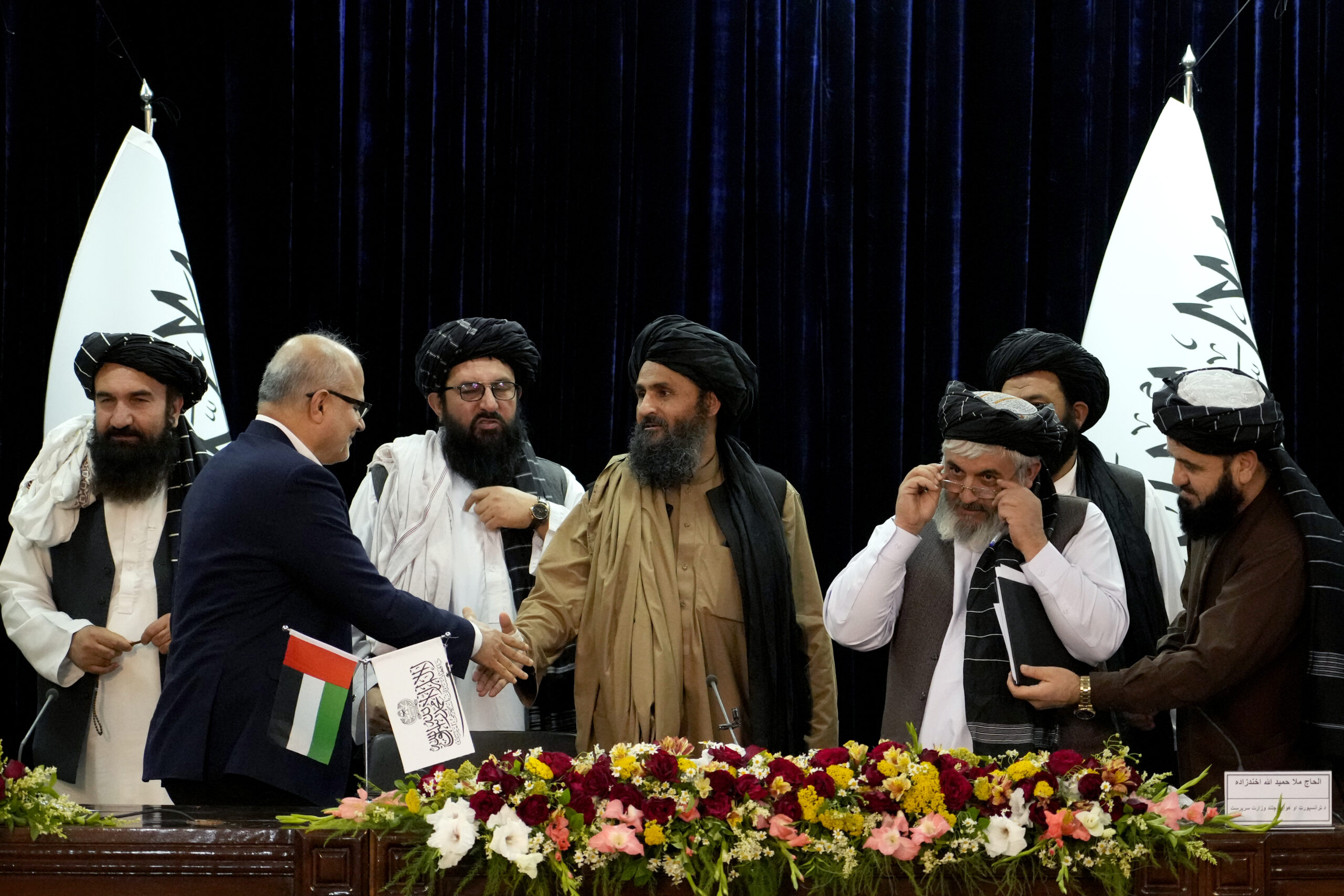

The first significant contract awarded by the Taliban to a foreign company was signed in January 2023, giving China’s state-owned Xinjiang Central Asia Petroleum and Gas (CAPEIC) oil extraction rights in the Amu Darya Basin. Completed in front of the Taliban’s Acting Deputy Minister of Economic Affairs, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, and China’s Ambassador to Afghanistan, Wang Yu, CAPEIC agreed to invest US$150 million in the first year and US$540 million over the first three years. Under the agreement, the Afghan government should receive 15% royalty payments for 25 years. Within a year of its signing, Bloomberg reported that CAPEIC has drilled 10 oil wells and quadrupled production to 5,000 barrels of oil per day, with aspirations to expand to 19,000 barrels per day. The oil is purportedly intended to be refined and sold in Afghanistan toward reducing the country’s reliance on imported petroleum.

CAPEIC’s contract established a partnership with the state-owned Afghanistan Oil and Gas Corporation. In July 2023, the independent Afghan media outlet Hasht-e-Subh published a detailed investigation alleging the Taliban had fired more than 400 employees hired under the previous government and replaced them with Taliban affiliates in positions that require technical expertise, procurement authority, or fiduciary responsibilities. According to Hasht-e-Subh, the new General Director of the firm, Naseem Rahimi, is linked to Heydatullah Badri, the Taliban-appointed head of Afghanistan’s central bank. Many of Rahimi’s relatives were found to have been awarded high-level positions in the company, and the investigation alleged that Taliban loyalists and fighters hired by or working as contractors for the state company received salary increases inconsistent with a Taliban-published pay scale.

In August 2023, the Taliban’s Minister of Mines and Petroleum, Shahabuddin Dilawar, announced a collection of mining deals and concessions valued at US$6.5 billion to both local and international companies. They included GBM and AD Resources in the U.K.; China-Afghanistan Company partnership; Ahya Sepahan, whose board Chairman is sanctioned former IRGC commander Ali Yousefpour; Parsian Iranian Companies; and Epcol in Turkey. Dilawar’s announcement also listed a series of other contracts signed with investors from the U.K., Iran, and Turkey in the mining and exporting iron ore sectors that would provide a 13% share for the Taliban over the span of 30 years. Several other deals of similar magnitude have been signed with foreign entities since the Taliban’s capture of Afghanistan.

Other major Chinese companies have looked to Afghanistan due to the mineral-rich country’s potential. These include Gochin, which offered a US$10 billion investment proposal in April 2023 to gain access to Afghanistan’s lithium reserves. Similarly, hundreds of Chinese entrepreneurs flocked to Afghanistan as a target of investment, particularly within the natural resource industry, in hopes of striking a mining deal and developing the necessary infrastructure to begin the extraction process.

Despite being publicly announced and formalized, such contracts are unlikely to come to fruition anytime soon. The Taliban lack the legal and policy infrastructure and the capability to oversee major projects. However, the projects offer the Taliban key opportunities to embolden their presence and position in Afghanistan, including bargaining power and finances.

The Taliban have proven their ability to leverage the resources that they seized through their capture of Afghanistan to cater to their interests as a terrorist organization. With an estimated value exceeding US$1 trillion in precious metal and natural resources, the Islamic emirate will likely continue to look to foreign companies in neighboring countries to support their activity and position.

Likewise, mining deals will require companies to extract the resources. The presence of these companies, particularly in the logistics and construction industries, may offer the Taliban opportunities to launder stolen state funds. Such industries routinely employ cross-border transactions that can be susceptible to exploitation to disguise illicit funds. Partnering countries, such as Iran, have used similar methods to launder money through the veil of financial flows that make illicit funds challenging to track in the construction industry. Enforcing sanctions can also be difficult under such circumstances. Contracts signed with entities from countries like China, Turkey, and Iran can operate outside Western currencies or financial institutions, thereby evading sanctioning authorities and complicating enforcement and investigation.

8

THE PATH FORWARD

After months of intense pressure from the U.S. Congress and the public, the Biden Administration released a position paper in April 2023 that details the reasoning for its hasty, botched, and deadly withdrawal from Afghanistan. In that document, the administration argued that “when the president made the decision to leave Afghanistan, some worried that doing so could weaken our alliances or put the United States at a disadvantage on the global stage. The opposite has happened. Our standing around the world is significantly greater, as evidenced by multiple opinion surveys.”

“The Taliban are demonstrating everything that they are and represent, but the international community feels it’s unable to do anything.”

– Zahra Nader

Editor-in-Chief, Zan Times

Public opinion surveys are not the reality on the ground, as our series of papers demonstrates. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan has left its population under the rule of a repressive and brutal regime, while U.S. adversaries have been emboldened and have profited from the Afghan people’s misfortunes. The White House paper also pledged that the administration “will remain committed to supporting significant humanitarian assistance and standing up for the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan, and we will continue to condemn and isolate the Taliban for its appalling human rights record.” Much work remains to be done to fulfill these commitments.

There is a path forward, however, to hold the Taliban accountable and to marginally improve the lives of the Afghan people, particularly women and minorities.

9

RECOMMENDATIONS

a. THE UNITED STATES AND THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY SHOULD FORMALLY DESIGNATE THE TALIBAN AS A FOREIGN TERRORIST ORGANIZATION (FTO) TO DISCOURAGE FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS, COMPANIES, AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS FROM CONDUCTING BUSINESS WITH THE TALIBAN.

Several terrorist organizations continue to maintain their relationships with the Taliban within Afghanistan or near its borders, including al-Qaida and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), an ideological ally of the Afghan Taliban that was designated as an FTO in 2010. Along with failing to prevent the spread of terrorism in Afghanistan, the Taliban continue to violate the rights of women and children and rely on criminal and corrupt activity to fund their organizational ambitions. Under U.S. law, a group can be recognized as an FTO if it is a foreign organization that threatens U.S. national security through premeditated and politically motivated violence. Designating the Taliban as a terrorist organization will tarnish any attempt at international legitimacy, stem the flow of resources, enforce travel restrictions of Taliban leaders, and prevent access to financial institutions. Under the designation, nations should recognize any official linked to the Taliban as a terrorist, updating current visa and economic sanctions. Likewise, financial institutions should create mechanisms that identify and share information on politically exposed persons and relative and close associates so that there is a cohesive effort that prevents the Taliban from accessing financial support and resources.

b. THE UNITED STATES SHOULD DESIGNATE AFGHANISTAN AS A PRIMARY MONEY LAUNDERING CONCERN UNDER THE USA PATRIOT ACT TO SIGNIFICANTLY INCREASE THE RISK TO FOREIGN COMPANIES TO ENTER BUSINESS DEALS WITH THE TALIBAN.

The United States and its allies can discourage the international private sector from entering into business deals that the Taliban can exploit. Instituting Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act will require financial institutions to collect additional information on transactions coming from Afghanistan. Furthermore, the United States can add conditions to Afghanistan-linked bank accounts in the United States that strengthen security measures. Concerns of potential links to the Taliban can threaten access to the American financial system. These measures will prompt the U.S. financial sector to be more cautious or completely disengage from all business dealings in Afghanistan. U.S. allies should follow suit and invoke similar measures to increase the risk associated with Afghanistan and possible facilitation of terrorist financing, with violations leading to sanctions or appropriate consequences from the responsible jurisdiction. This would further disrupt the ability of international financial institutions and private companies to provide business services the Taliban could exploit to access the international financial system. Exceptions should be made to international humanitarian organizations that operate in Afghanistan to ensure that Afghans don’t suffer additional repercussions due to the Taliban’s rule.

c. THE UNITED STATES SPECIAL INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR AFGHANISTAN RECONSTRUCTION (SIGAR), DEPARTMENT OF STATE, DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY, AND USAID SHOULD HARMONIZE INFORMATION-SHARING PRACTICES THAT ENHANCE TRANSPARENCY AND U.S. EFFORTS IN AFGHANISTAN.

The House Committee on Oversight and Accountability recently declared that a lack of coordinated efforts between U.S. Cabinet departments and SIGAR hamper the ability of the Afghanistan watchdog to maintain consistent reporting on conditions in the country. As the leading partner in assessing humanitarian and governance conditions in Afghanistan, the United States should strongly encourage lateral cooperation between all agencies that support SIGAR’s mission. Information sharing should be a priority between all parties, along with unimpeded cooperation on any requests sent by SIGAR.

d. THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY SHOULD COORDINATE EFFORTS TO INVOKE HUMAN RIGHTS AND ANTI-CORRUPTION SANCTIONS AGAINST TALIBAN LEADERS USING MECHANISMS SIMILAR TO THE GLOBAL MAGNITSKY ACT.

The Taliban’s systematic use of corruption and human rights violations is consistent across the organization’s range of illicit behavior. Currently, 35 countries, including the United States and members of the European Union, have a mechanism like the Global Magnitsky Act that targets human rights violators and corrupt actors and grants them the power to impose travel and financial sanctions against the Islamic emirate. All countries with Magnitsky-like legislation should invoke these measures, including asset freezes and visa bans against Taliban leaders. U.N. member states that don’t have legislation related to the Global Magnitsky Act, but have publicly condemned the Taliban, should codify similar laws.

e. THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY NEEDS TO TAKE A MORE DEFINITIVE ROLE IN CONFRONTING THE TALIBAN’S ABILITY TO EXERCISE CORRUPTION, PROFIT FROM KLEPTOCRACY, AND CARRY OUT HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES.

There has been a failure to hold the Islamic emirate accountable for its corrupt and illegal activity, undermining international efforts to pressure the Taliban. Key geographic stakeholders, specifically the governments of Qatar, the UAE, and Turkey, should lead regional efforts to address the Taliban’s human rights abuses and financial networks, including by prioritizing resources to support investigations and the location of Taliban assets. Public convenings led by multilateral organizations or influential states should condemn and address the Taliban’s human rights violations as well as corrupt activity that impacts Afghans and drives further instability. Lastly, the United States should take a more active role in multilateral conversations that concern the Taliban and Afghanistan to avoid further ceding the space to authoritarian actors.

Acknowledgments

Dozens of conversations with experts, advocates, and practitioners from a wide range of backgrounds and experiences significantly aided this report’s development. Their expertise was invaluable in mapping areas of concern and identifying subsequent policy recommendations. The George W. Bush Institute thanks each of them for their contributions.

Kasra Aarabi, Fatema D. Ahmadi, Jason Brodsky, Pashtana Durrani, Naheed A. Farid, Jeffrey Grieco, Saeid Golkar, Valerie M. Hudson, Said T. Jawad, Habib Khan, Richard Kraemer, Zahra Joya, Steve LePlante, Esmat Mohib, Sayed Mahdi Munadi, Zahra Nader, Martin Rahmani, Mahmoud Saikal, Nilofar Sakhi, Sima Samar, Arian Sharifi, Omar Sharifi, Melissa L. Skorka, Jodi Vittori, Niva Yau, Juan C. Zarate, and Matt Zeller.

Due to ongoing safety and security concerns in Afghanistan and the sensitive nature of these reports, some experts we spoke with cannot be cited publicly. Though we are unable to name them here, the project team remains incredibly grateful for the contributions of these individuals to this effort.