Two Texas principals share their experiences leading students and teachers through COVID-19, how they plan to address learning loss, and what they are hopeful for in the coming school year.

In a conversation moderated by Anne Wicks, The Ann Kimball Johnson Director of Education Reform at the George W. Bush Institute, and Andy Rotherman, Co-founder and Partner of Bellweather Education Partners, we are reminded of the impact principals have on their schools and the crucial role they play in helping teachers and students succeed against all odds.

Keri Flores and Tamara Albury, both Fort Worth ISD principals, share how their schools, students, and teachers grappled with in-person education and virtual learning. They also share what lessons they’ve learned from this year and how those lessons have impacted their outlook on education. Flores and Albury are both a part of the Bush Institute’s School Leadership Initiative.

Transcript

Anne Wicks: All right. Welcome, everybody, to today’s conversation. I’m so pleased to introduce you to two really experienced principals, and we have a great guest host with us to have a conversation about what it’s been like to lead schools this year and what our principals hope for next, for both their students and for their teachers and their campuses going forward. First, let me introduce Andy Rotherham, who is a co-founder and partner of Bellwether Education. Andy writes, widely speaks all over the place about education issues. He has co-founded, advised a number of education organizations over his career, and Bellwether works with many educational organizations to help them innovate to improve student outcomes. So, Andy, thank you so much for being here.

I’d also like to introduce you to our two great principals. First, Tamara Albury, who is the principal of the Young Women’s Leadership Academy in Fort Worth ISD here in Texas. So Tamara’s been a teacher, a curriculum writer, a coach of other educators before becoming a principal, and she also is widely traveled, which she hasn’t been able to do much of in the last year and a half, so if you run into her in an airport somewhere, you can ask her all about her adventures. So, welcome, Tamara. I’d also like to introduce Keri Flores. Keri has been in Fort Worth for over 20 years. She is the principal at Western Hills High School. Is this your 12th year as a principal, Keri, 11th year?

Keri Flores: Yes.

Anne Wicks: So you’ve been around the bend a few times with leading a campus. I know you have a lot of experience and insight about that. So why don’t we actually start? Keri, why don’t you tell us just a little bit about your campus, and then, Tamara, we’ll have you do the same.

Keri Flores: So Western Hills High School is on the west side of Fort Worth. We have about 900 students, about 880. We are in an area that is very, very transient. We probably have about a 30% mobility rate, about 89% economically disadvantaged, 45% Hispanic, 35%, I would say, African-American, 20% white. Like I said, very transient. We do service an area of town that is really known for high crime, a lot of movement, a lot of mobility. But all that and I can still say that we’ve got really, really good kids and I’ve got a dedicated team of teachers that when you look at, say, our state assessment and state scores and you compare them across the district, we’re one of the top-performing, just our traditional high school. So our kids come to learn, our teachers are here to work, and it’s a great place to be.

Anne Wicks: Tamara, tell us about the Young Women’s Leadership Academy.

Tamara Albury: We are a school of choice within Fort Worth ISD. We service over 40 different zip codes, over 40 different elementary schools within the district. Our enrollment next year is slated to be 524, and it’s college prep. So our demographics were 90% students of color. 76% of our students live at our below the poverty level, with about 40% of our students being labeled at risk for not graduating high school. We are graduating our sixth graduating class this year, and every year we’ve had 100% graduation rate. 100% of our students are accepted into four-year institutions, and US News and World Report was just released, so we’re number one in Fort Worth, we’re number 17 in the state of Texas, and 117 in the country. So we are very proud of the work that is done on our campus. It’s about college prep, it’s about college access, and not just going to college but graduating and becoming those leaders of tomorrow. So that’s our goal, and we’re 100% female, so we’re amazing in just that sense.

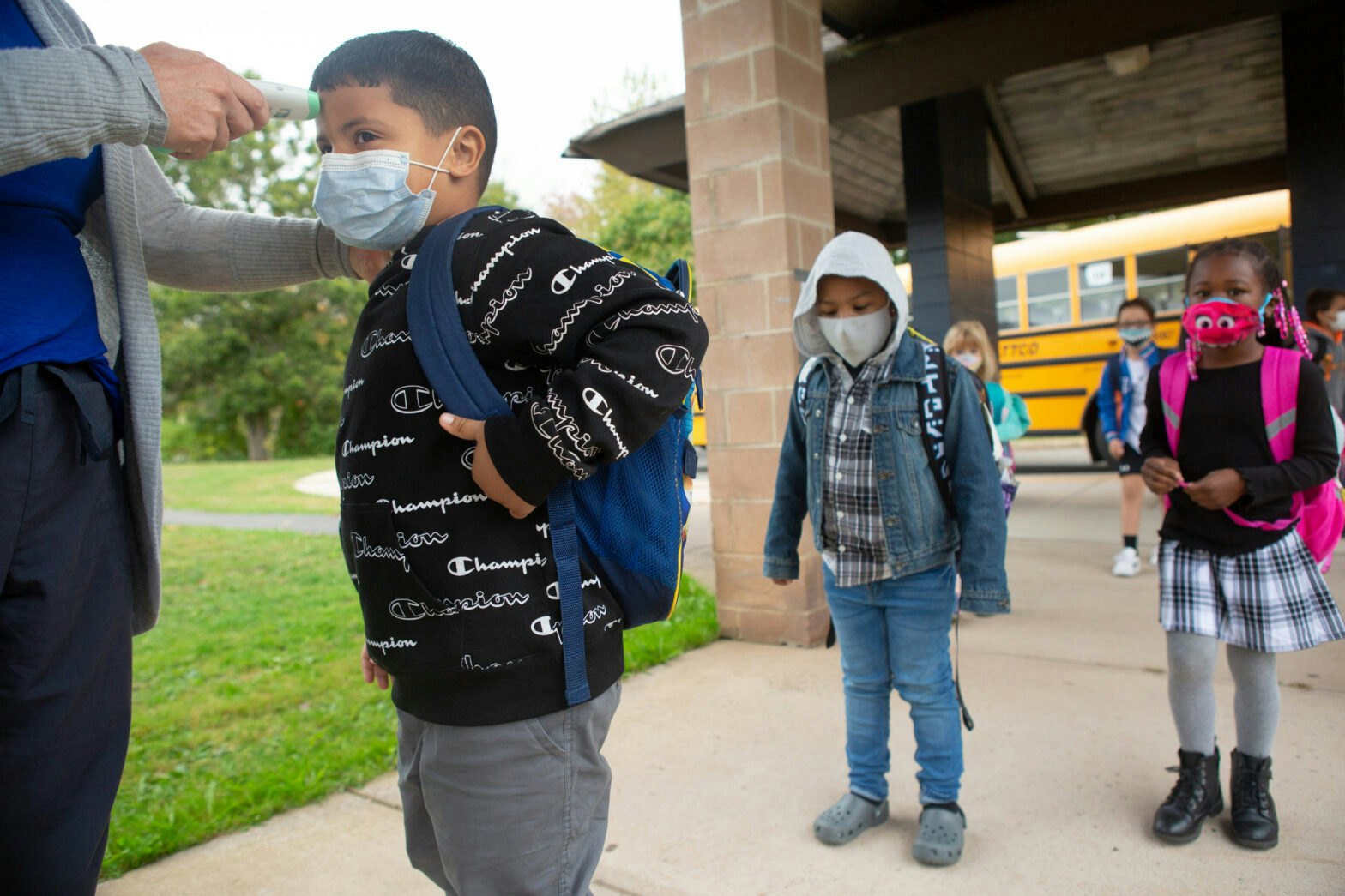

Anne Wicks: Well, I’ll kick us off. We’re going to have a broad-ranging conversation, but here’s the first broad question for you. Both of your campuses have been in-person for much of the year, but I also know you’ve grappled a little bit with hybrid or virtual instruction along the way. I’d love for you to tell us a little bit about the biggest challenges you’ve had in operating a campus this year. What does it really look like day-to-day?

Tamara Albury: I would say one of the first things, socially and emotionally, it’s been really challenging. I think the career of education is very much about connections and relationship. We always talk about teachers building relationships with students, and with the virtual platform, it’s very hard for teachers to build those lasting relationships. You have counselors that can’t touch children, give a hug if they’re in a social-emotional state. So, basically, it seems like everyone’s been operating in a state of trauma, leading in trauma, learning in trauma, teaching in trauma, having to change our focus in terms of a traditional way and trying to stop forcing the traditional, normal way of doing things into this new way of doing things and thinking about the workday, thinking about students when we assign them assignments not necessarily doing it on a weekend because they need a break. They need a break from the Zoom just like we all do.

Then instruction because, with this new platform, we have veteran teachers that are now first-year teachers again, and people, when it comes to being effective … I’ve been effective my whole entire career as a teacher, and now I don’t know how to grapple with this. So that whole idea of value of teachers, value of leaders because everything is so different and you have to be innovative, it really does test your ability to be innovative because there are so many different things you can’t control. Being innovative is the only thing that you can control.

Keri Flores: And just to piggyback a little bit on what Tamara said, I think relationship and connection … A big thing in a traditional high school, it is all the traditions that you have, right, and the things that kids are involved in. This year, our number of students involved in choir or involved in band, involved in any kind of a sport, is so, so low that it’s really hard to get any kind of excitement around that. I would say, at the beginning of the school year, when we opened up, we’re operating with probably less than 50% of our kids that chose to come back in-person, so you have a lunch and it is so … And you’d never think a high school principal would say this, right, but it’s too quiet. The hallways are too quiet. It’s like the kids walk around almost like zombies. I do think that relationship and that connection is missing.

One of the things that we really, really have struggled with here is that engagement, getting students engaged in the … I would say the majority of the kids are doing the work, engaging with their teachers in some form. Maybe they’re not logging onto the Zoom, but they are emailing the teacher, they’re doing the work that’s posted. But we have a lot of kids that are choosing to stay home or choosing to stay virtual because they’re working. They are now a supplemental income in helping their families, and I think that some of the employers are taking advantage of the situation. We’re calling kids and saying, “This isn’t working. We need you to come back in-person.” They’re like, “Well, I got to check with my job.” I’m like, “Well, no, school is your job, right?” But they need that income, and I do think some employers, they’re getting to reap the benefits of kids being able to work.

We’ve got kids now that are watching younger siblings because mom and dad are working and now it’s free daycare. Parents don’t have to pay for taking their child someplace. So older brother, older sister can take care of the little ones, or mom and dad can work and … Again, to us, it’s an engagement. We’re having a hard time getting a small percentage of our kids to really engage and do what we need them to do. We worry about graduation. We worry about passing. We worry about retention rates. I think that’s been a struggle.

Andy Rotherham: As Ann said, you guys were in school for much of the year. Texas has been different than a lot of states in that way. But you also were delivering some instruction virtually at different points during this and so forth. Talk about that and how that’s worked, what didn’t work. What are any big learnings and so forth that you have from the experience that was forced on you with virtual?

Keri Flores: Well, I think that we’ve had different types of virtual, right? When we started this at the end of last year in March, with the beginning of the pandemic, it was a what are we going to do … We had an online platform that all students were enrolled in this one online platform. Teachers were helping to make sure lessons were uploaded. So we went that way for a while. Then we started this school year off. We had a little bit of mixture, where some kids came in-person, some stayed virtual. Now, we have a third option to where kids can be either all in-person … So we have three options. They’re either all in-person, they’re hybrid, or they are all virtual.

I think that the hard part with virtual is that we’re seeing that students still need guidance, right? We’re still talking about adolescents. We’re talking about 14, 15, 16-year-olds that I think sometimes some people think, “Well, they’re in high school, right? They should be able to log on and do their work because they’re responsible students. You’re in high school now.” I think, even with the virtual, that it still takes a lot of guidance from a teacher and a lot of check-in with a teacher.

I think a positive that has come out of this is that in the past, for me, I can only speak for my experience, at the high school level, teachers are reluctant to call home and to make those parent contacts. But, through this, they’ve had to. We’ve had to exhaust every kind of resource we can to call, do home visits, emails and texting, Google Voice, tried that. So teachers, I think, are a lot more comfortable now of having to call home. I definitely think virtual works for some kids, but for others it has to be guided. It cannot just be thrown out there and let them try.

Tamara Albury: I agree with everything that Keri said. We have had a few students who really thrive in that environment, and so I know, a lot of times, when we talk about differentiation, I think that virtual can be a differentiating way of delivering instruction for certain students. Some students do well, right? When you think about college, some people do well with the online courses, and some people need brick and mortar. So what it has done is it’s allowed those students that online is for them … They’ve been able to thrive and really do well in that environment.

Also, for families, I’m going to say virtual instruction has been a great bandaid for some families who have lost income because of the pandemic and a variety of things. A lot of our kids are now having to work, you know what I mean, work to pay not just the cellphone bill but rent and cover their basic needs. So having that flexibility allows for students to still obtain an education but meet their needs at home. I think that there is a place for virtual learning. It should not be a blanket one size fits all, and there definitely needs to be a way to identify those students who really thrive in that environment and those students who thrive more so in in-person.

But I think, also, one of the dangers is that I go back to thinking about text messages and students when they send text messages and understanding tone, understanding all those things that you need human contact to do. So the virtual instruction has resulted in students not having that human contact, right? As creatures, we need that connection. We need to be able to have those social interactions to be able to really exist in society. That’s one thing I would say that is definitely necessary, so if virtual instruction is something to do in the future, like an option for a district, there needs to be a social component incorporated within that for students, really, to be that leader or to be successful in life. Theoretically, you cannot sit in front of a computer all day and be isolated. At some point, you have to deal with people, and so you have to understand how to deal with people.

I think one of the other things, too, as it relates to teachers, you have a lot of teachers who are very reluctant when it comes to professional development and technology, but what this has taught us is that everyone is capable if they have to do it. So all of those people who want to push back and things like that, they did it, they embraced it, and they are thriving in that environment with technology and virtual instruction and how to pivot and all those different things. I think that, one, it allowed people to see, really, what they’re made of and their capabilities to that next level. So it really did help teachers to build their capacity as instructions and their tools with their variety of platforms.

It helped to have teachers who would normally, we say, sit and get, where they stand and deliver … “Now I have to be more interactive, now I have to be innovative, now I have to figure out how to engage students. Where, before, I could rely on standing in front of the classroom and lecturing, I cannot do that anymore, not if I really want to engage my students and ensure they’re achieving at certain levels.” So it has forced people to move in their craft and build the capacity of educators.

Andy Rotherham: You made an interesting point there, which I think … You have to hold two ideas in your head at the same time, right? For some subset of kids, this has actually been good. The virtual has opened up some different things for them and so forth. For most kids, this has been less than ideal, and so later on this conversation we’ll talk about learning loss, unfinished learning, and all that. But for right now, do you have any plans to … I know everyone’s hair is on fire coming out of the pandemic, but are you starting to think about … You were saying that this does work for some kids. Are you starting to think about what that might look like and changes going forward, innovations that you would go ahead and keep for coming school years based on this, or is it just too soon because you’re still putting out fires every day?

Tamara Albury: I think it’s too soon, but one thing that I think has been really great, on my campus, we do a lot of field trips, and so students missed a lot of classes and teachers are, “Algebra, they need to be having algebra, this experience, they need it,” kind of thing. So what this has done, though, it has created a database for teachers that if a student is missing a class, this is an opportunity for them to get the instruction even if they’re not in class, right? It does really offer a lot of different opportunities in terms of how we think of school and how we think of what we do.

I know we were contemplating the whole virtual academy. I’m not sure where our district is on that piece because we take our guidance from them. But I think, definitely, putting aspects of the virtual learning, in terms of the instruction cycle, would be a great idea. For example, if there’s a student who has not mastered an objective, here is a video you can watch so you can learn, get some questions, and get that extra tutorial. That individualized learning can come from all of these different lessons that are virtual that were not available before.

Keri Flores: Yeah, and I was, as Tamara was talking, kind of thinking about credit recovery, right? In the past, traditionally, if a student fails algebra, we tend to put them in a trailer course, try to compact in the semester so that they’re ready to take geometry compact in the semester. Now, I wonder, could we or what would it look like to do credit recovery in a virtual setting while the student’s still progressing, maybe, in the geometry but the algebra … Since the teachers now have the platform, they know how to use the Google Classroom, they know how to tailor a lesson, compact it within a virtual setting, can students try to regain credit that way while they’re still moving forward so we’re not holding kids back so much, if that makes sense? I wonder if that could be something that we explore or look at or what those options would look like.

Anne Wicks: Let’s talk a little bit more about instruction because I know that’s been a key thing for you all and we know, nationally, there’s been a lot of talk about, well, there either should be state summative assessments, in Texas, of course, that’s the STAAR test, and those give us that once a year shot of understanding students’ learning. Of course, those didn’t happen last spring. All states suspended those tests. They’re happening in Texas, at least, in an adapted version, I guess I would say, for this spring. But I’m really curious for both of you how you’ve tried to measure learning on your campus. What are you using to understand where your kids are and then help your teachers design their instruction accordingly? I know you both do this in your practice, so I’d be curious what that’s looked like this year and if it’s been different than you’ve done before.

Keri Flores: Yeah, I think it’s definitely been tough. I’m not going to lie. It’s been tougher this year, I think, because our state and our … We are so heavily driven by state assessments that we rely on that data. We’ll do benchmarks and things like that, but we found out this year with … We tried doing benchmarks in the fall as a district, and even when we tried doing it like, okay, the in-person kids are doing it, then the virtual kids, they could do it on their own, well, we were seeing that, through the system that they were taking the virtual test on, they would be on the test for eight minutes and they scored a 100. We’re like, “Hmm.” It was easy to tell this is not valid data because they can clearly look at answers and things like that. So we suspended benchmarks, so teachers didn’t have that.

Again, another positive, right? I do think we’ve got to look at what have been some of the good things that has come out of this, is that it has forced teachers to work together more to come up with common assessments that align to what they’re teaching. It’s forced them to rely more heavily on formative assessment and being better skilled at how to embed and use a formative assessment, take that data, change what I’m doing. So those have been, again, like Tamara said, some forced learning. That is a positive thing. That’s a good thing that we’ve been saying for years, but now it’s like, “Okay, now, you really have to do it,” and it’s working, and they’re seeing the benefits of some of those things.

Tamara Albury: We also have the MAP data, which tests our students with ELA and math and then their growth as well as achievement. On our campus, because all of our students are taking AP exams, what we’ve begun doing is providing our students with the opportunity to take mock exams to assess, really, where the deficiencies are, the strengths, the opportunities to fill those in and make sure that they are filled as much as possible as we head toward the exam. It’s so hard to really … Because there’s so much social-emotional trauma just happening with our students that I think … We just had our Panorama data, which really assessed the emotional health of our faculty as well of our students, where our students are feeling isolated.

So what we’ve done a really good job on, I think, as a district is really focusing on that social-emotional because if students are not socially and emotionally well, there is no learning taking place, no matter what you do. Students, they’re home in whatever their home situations are for the last year and a half, and so it’s just been a challenge for everyone. While we do have assessments to see where they are and what we’re working with, I think, definitely, we have done a lot of work around making sure that our students are okay.

Andy Rotherham: Both of you, what advice do you have for parents, for your colleagues elsewhere, particularly states that aren’t as far along as Texas in terms of the opening, and then for policymakers?

Keri Flores: I don’t know if it’s personal, right, or if it’s just my opinion, but I think that we are seeing … I agree with Tamara. There is a place for virtual learning, and I do think some kids can benefit from it and some kids do really, really well on it. But I also think that we are seeing the value of face-to-face instruction, and you can’t replace face-to-face instruction. We’ve got too many kids, as Tamara said, who are dealing with SEL trauma that need connection with adults. We have too many kids that are failing, and we as teachers need to get them here so that we can support them and help them and help guide them to be successful. In my opinion, I think this has really shown that getting face-to-face and in-person with a teacher far outweighs some other of the concerns that we’ve had.

Tamara Albury: Definitely. I agree. I think that there needs to be a bigger push, this is my personal opinion, as it relates to social-emotional and just making sure that our students are in a place to learn. They’ve been living in a trauma for the last year, and so kind of just to piggyback on what Keri was saying, is that the reason why in-person is so important, it’s part of that idea of touch and connectedness. They don’t have that looking at a screen. Even though there’s someone on the other end, a real human speaking to them, knowing that someone cares about me and I’m in that space and they care about my wellbeing, they care about my learning, they care about me as a human, it’s invaluable for our students. I really think that, as we enter the post-pandemic, we need to really think about what are the effects of learning and living in trauma for a year, I don’t know if that data exists anywhere, and use that to help us with our comprehensive needs assessment of what we need to focus on as we’re entering in a post-pandemic era.

Because if we don’t put those at the forefront and we don’t address those things and we just go head into academics, academics achievement will never be reached because all of those other things … If I’m dealing with I didn’t sleep last night, I didn’t eat breakfast this morning, I got into a fight, whatever it might be, I come to school, all of that is heavy on my heart, heavy on my head, and then I have to sit down and write a two-page essay. My mind is not focusing on that, and so that really needs to be at the forefront. They used to tell you before you took a test, “Make sure you have a great breakfast and you have positive thoughts and you go to sleep early,” right? So all that stuff, it plays a role. It plays a huge part. If that is not a part of a conversation and it’s not just about the academic standards but the social-emotional ones as well, we’re not ever going to make up what this last year has taken from us in education.

Keri Flores: Those are things that we worry about in a regular school year, too, right? That’s part of working at a high poverty, urban school district. I think what we’re also looking at is we’re looking at a freshman class that really hasn’t had a freshman class. So when we’re talking about next year and as a district, which I love, that we’re going to freshman [inaudible 00:24:41] and a freshman success team and really have this emphasis on how to support our freshmen, but we also have to be thinking about our sophomores and how are we transitioning them into high school because some of them haven’t been to high school at all. It’s this transition of not just one class that we have to worry about or not just the fifth-graders. It’s almost a two-year gap in kids that we’re going to have to really, really support and work with.

Andy Rotherham: Tamara, you mentioned Panorama, which, for people who don’t know, that’s a commercial vendor that provides surveys and so forth for schools so you can get a sense of what’s going, climate surveys and so forth. But take us one level down, that or other things that you’re … Kids are coming back, as you said. They’ve experienced trauma or are experiencing trauma as a result of this. As Keri said, some of that is, unfortunately, stuff that happens in any average school year, but it’s obviously more acute with everything that’s going on. But kids have experienced lots of different things. On a personalized level, how are you identifying what’s going on with kids and then what are the supports and so forth that you can put in place?

Tamara Albury: I meet all the time with my counselors and my interventionists to gauge where are my students, what’s actually happening with them, but also making a concerted effort to provide them with the opportunity to express themselves and to feel safe. We call them safe spaces, where they can express themselves, they can have others that are supportive around them to give that some level of connection. We’ve also started something called RAKtivist, so it’s random acts of kindness plus activist, where they are doing kindness. They have a kindness quote in the morning, and they have things that they’re doing, putting around the school specifically, to encourage that whole idea of kindness, being kind to yourself, being kind to others. It’s like you have to retrain students how to do school, even students who have been on campus and have gone home and have been virtual for a couple of months. When they come back, they’re very lost because the world has gone on without them, and so that’s something we have to be mindful of.

I think, as Keri said, we have students that have never stepped foot on campus, never stepped foot on campus, whatever that looks like, and so they’re lost. Transition and change is really hard for anybody because change is about loss of something and how exactly you process that level of loss. So I think that, definitely, grace needs to just continue. It shouldn’t just be during the pandemic, but post-pandemic we need to have some level of grace of how people are processing change when they come back, people don’t process it always the same way, but providing people wherever they are at a variety of different levels the support to be successful in that environment.

Keri Flores: Yeah. So, this year, with our attendance, since September, our kids, when they check into their class for an attendance measure, we created a Google Form and they click on a link. But we also have within that link questions for them around just how are you feeling, do you need a counselor to contact you, do you need an assistant principal to contact you. Every day, in every period, the students are sending in how are they doing. By this time, I don’t know how much they’re really taking it serious or not. So we’ve been trying to identify kids through that.

I was thinking for next year … This is our first year having an advisory period, and it’s been kind of an odd year to have an advisory period. But, next year, I definitely want to keep it. I feel like there’s a lot of value in having an advisory period. So I’m looking at purchasing with our Title I money a SEL program that will help train our teachers also, and it’s a resource right there for my teachers to use within this small group and really give my teachers tools to build that sense of community with kids again, how to make connection and building a relationship with students again. I think our teachers are going to need the support and the training of how to redo school with kids again and how to get the kids back connected.

Tamara Albury: I think, definitely, coming at it from a point that everyone has been living in trauma, trauma-informed needs to be the buzzword for everyone as a strategy to navigate a trauma-informed campus, a trauma-informed school. What does that mean as an educator? What are things that they need to think about when they’re creating lessons, really getting to know their students, and what that looks like? So one of the things that we’re also doing is we’re trying to become a trauma-informed campus because, one, we know that all of our students have been living in trauma, and so we know that, going forward, we need to mindful of that in all that we do. That’s going to be our foundation for providing services to our students.

But, like Keri, we also had a Google Doc where students would answer questions every day. What that actually did is it helped our interventionists and our counselors catch issues early. Based upon the questions, they could gauge where a child was and follow up with the child, follow up with the parent. That, I think, is a great thing because we haven’t been that diligent or that hands-on, making every effort to connect, as much in person. So that’s something that we really would like to continue, that ability to keep that eagle eye on our students to understand because the pandemic and the traumas and the feelings aren’t going to end because the pandemic is over, right? We’re still going to deal with the effects of this in a way that we don’t even know because we’ve never really dealt with this in this way before.

Andy Rotherham: There’s a debate that’s broken out about learning loss or unfinished learning, and the debate is two-fold. First of all, what to call it, and that’s turned into just a huge fight about semantics, and then, also, hopefully not obscured, more importantly, what to do about it because a lot of kids have had a really disrupted year over the last 12 months of school. There’s obviously some impact from that. Can you talk about what are you doing about that and how are you thinking about addressing it, and then how are you talking to your teams about it and are you being particular about saying unfinished learning versus learning loss? How are you approaching that with your teams?

Keri Flores: I think we refer to it more like learning loss, right? I don’t know if we’re at the point yet where we are talking about how we’re going to make those gains next year. To be honest with you, I think a lot of our concern right now is centered around this year and how are we going to help kids that are not making gains, not making progress in their classes, and we’re seeing that through grades, we’re seeing that through loss of credit. So there’s a lot of movement around, a lot of discussion around how are we helping our students, how are we supporting our students to regain credits? How are we supporting them to make up credit and those kind of things? There’s conversation around that, yes, I would say so.

I think there’s conversation around summer school. What will summer school look like? Are we going to have a summer school? Are we not going to have a summer school? Will it be in-person? Will it not be in-person? If I had my choice, I’d rather it be in-person. I think our kids do better with our teachers, I do. We will have kids that are going to have major, major gaps, so if we can get them to come to summer school to start weeding out some of those gaps, that’d be great. I feel like right now, like I said, we are so busy trying to get kids to recover from first semester, that either they didn’t engage or they didn’t pass, that we haven’t been focusing quite yet on what will next school year look like, how am I going to compact and get those kids caught up?

Tamara Albury: And I think we refer to them more as opportunities as opposed to learning loss, a deficit sort of way of looking at it. But I think, definitely, to what Keri was saying, is that right now we are focusing on our students, trying to get them to graduate, trying to get them to make sure that they are doing what they need to to go onto the next grade and things like that at this point. But our teachers are very diligent in terms of what are students are needing using our MAP data, which MAP is a program that our district has purchased to assess where our students are. So seeing where are the objectives that our students, what haven’t they mastered, and addressing them more in that way as opposed to the learning loss.

We start in sixth grade, and so our sixth-graders coming in next year haven’t tested, really, since third grade. Because they’re in fifth grade this year, and when they applied or when all the data … Anyway, third grade was the last time that they actually did any kind of real testing, right? So it’s been such a long time that it’s not even real-time to see exactly where they are, and so because the assessments aren’t such, we’ll have to wait until STAAR to see where our students are and where are those opportunities next year that we’re going to have to really fill in from that vein.

We are still looking at summer school and what that’s going to look like for our students. I think it should not be a compliance thing just because you failed but actually targeted as much as possible and differentiated for our students in terms of where there loss lies as opposed to you didn’t pass this class. But what exactly is it that you are missing or are needing? I think that we need to continue in that vein for our students for it to really be effective and successful.

Anne Wicks: Really interesting because I keep thinking so much about how this is time that’s been stolen from kids. The kids haven’t done anything, right? This has been forced on them, and this time is stolen so it’s sort of how do we as the adults in the system … What’s our responsibility to right that, however fumbly, stumbly, awkwardly, right, as we go? So we talk a lot about what students need, and I’m curious. You both manage a lot of adults on your campus, and you have peers who have been leading on campuses, which can be a lonely, hard task in a normal year. So I’d love to know, what do you recommend to those who are making decisions out there in the world? What do teachers need and what do principals need as we move forward?

Keri Flores: Teachers need a clear direction of what type of instruction they’re going to be doing and not a dual instruction platform or program. I think it is not sustainable to keep doing what we’re doing this year, where teachers are teaching both the in-person kids and managing the virtual kids. I know here in Texas, right, TEA has not come out with an announcement yet or a ruling of can there be a virtual option for next year. I’m anticipating that to probably come, but my teachers keep asking all the time, “Is next year going to be like this year,” and I don’t have a good answer for them yet.

I don’t want to lose really good teachers who are exhausted and who are struggling with this kind of dual platform, per se, because it is tough. I think teachers need to know that you’re going to teach your in-person kids or maybe I’m a teacher that I do really well with the online, I am super tech-savvy, I can manage this, I’m good at reaching parents. Great, then you can do the online, and we’re going to put you here with the online kids that want to do that virtual setting and separate it from the school, if that’s possible, if that’s going to be allowed or not. Like I said, just doing what we’re doing now is not sustainable. Teachers need one set of a guidance, like either you’re working on this virtual or you’re working on your in-person babies and just have some clear guidance.

Tamara Albury: I would just say, on the social-emotional end of that, what I’ve found is that my teachers need connection, right? At the very beginning of the year, as a leader, I would try and find ways to appreciate them, free food or whatever it might look like. Usually, food makes everybody happy. Usually, right? But-

Anne Wicks: Time-honored solution, right?

Tamara Albury: To everything, everything. But what I noticed was that it was not as effective as it had been in the past, but providing opportunities for our teachers to connect in some way was so much more impactful, whether it was a who am I game or things like that. So I think, socially and emotionally, teachers, they need their needs addressed, too, with what they’re dealing with in the profession, their efficacy, are they being effective, wherever they are, but having some training so that they can process in terms of … It’s not that you’re a bad teacher. Maybe the strategies that you previously used don’t work in this setting. But what we need, to help you to develop new strategies, right, because teaching is such a personal thing. So what happens is that now I’m not effective, I’m a bad person, I’m a bad teacher, when, in fact, it’s more about the strategies being used, so helping them to process through what they’re going through.

Andy Rotherham: All this federal money’s coming down, just stunning sums of money coming down to local school districts. If you ran the zoo, what would be your priorities with that money?

Keri Flores: For me, when I think about it, in our district, we’ve lost a lot of students in our enrollment, so our enrollment has gone down. We all know when enrollment goes down what that means, right? We’re in the process right now of a lot of schools are looking at surplus in teachers, and we’re having to make those decisions of cutting classes, cutting teachers. I think if I had the money I would fund FTEs, fund teachers on campuses so that the campuses can have smaller class sizes so that you can regain some of the lost instruction with a smaller class size. It’s very, very hard to fill holes and gaps when I’m dealing with a biology class of 30 to 35 kids. If I could fund and give campuses some more teachers, that would be excellent, to be able to lower those class sizes so that you can give a little bit more individualized instruction with those kids.

Tamara Albury: I would say, in addition to that, probably no shocker, but, socially and emotionally, I think every campus needs at least one or two interventionists or psychologists, whatever it might look like. But there needs to be greater funding on that social-emotional piece because with the staff that is currently allotted, social-emotional have not been as much of a priority as it should. With everyone coming off of a pandemic in a post-pandemic world, there is just so much there that really has a potential to result in more school suspensions, more learning loss, more disruptions to the learning environment. So if we don’t address that and that is not addressed and funded in a way that can help our students be successful, we’re going to see the effects in a great big way, and that is something that I’m truly scared of, to be very honest, because I see it.

You see the trauma during the pandemic, and you can only imagine what that looks like post-pandemic because you’re not even seeing all the students. You’re not seeing those students who are home. A lot of times, we always not joke but we say when students go home over break, when they come back, it’s a rough week. It’s a rough week when they’ve been home and they have not been at school. So now they’ve been home for an entire year? What is that going to look like on our campus? If we don’t have a strategy or structures in place to meet our students where they are and help them to learn how to do school again, it’s going to be very devastating for education as a whole.

Andy Rotherham: So I just want to hear from both of you, end on a positive note. The great thing with education, you get to work with kids, it’s exciting, it’s always about the future. What are you excited about? What are things coming out of this that you see that are keeping you in a positive frame of mind and moving forward and things that you think are going to be better as a result?

Tamara Albury: One of the great things is that, in terms of relating to parents and connecting with parents, this has been great because I do, on Fridays, coffee with the principal, and it’s virtual, or if they’re at night, it’s at nighttime, and there’s more parental involvement because I can make dinner and still listen to what’s going on at school. So that truly has been a blessing, to learn that technology really is a way to really incorporate more parents into what we’re doing and so that they’re more a part of the process. That really has been really exciting. I’m excited to continue that piece and have more parents be a part of the process going forward.

And I miss my kids. I love my sixth-graders. They’re just amazing. So it’ll be great just to see them, that energy. I think, as educators, the thing is that we thrive off of the energy of our students, the energy of learning, the excitement of new things, the excitement of being in school. That helps to energize us as educators, and I think being deprived of that has really been hard on us during this pandemic.

Keri Flores: Well, I think I’m in a unique situation that my school has had a complete renovation during this entire pandemic. They have gutted the entire building from the upstairs to the downstairs. Not an inch has been spared. I think the contractors got lucky during the shutdown, so that made their work really progress a lot faster. They had access to the building. So I am looking forward to … I keep telling some of my people around me, “It’s going to be like Men in Black, right?” When we come back in August, we’re going to wipe this clean from our mind. None of this happened. We’re starting fresh in August. We got a brand new building. We’re going to do a big open house, just hanging onto almost that sense of normal, of getting kids, like Tamara said, back in the building, getting school spirit back up, trying to do all the fun things that we’ve missed on.

Keri Flores: Like you said, it’s fun, exciting right now to see our seniors graduating and getting to do the scholarship things. Those are great, but it’s hard when you can’t really celebrate, academic sweatshirt and you’re just passing it out, the sweatshirt. In the past, you’re doing big pep rallies, decision days, always big pep rallies, and now it’s very, very low-key. So I’m just ready to do some of the old things we used to do, the traditions, and making it fun.

Anne Wicks: Well, at the Bush Institute, we’ve worked with and for on behalf of school principals now for almost a decade because we just believe so deeply in the outsize role that great principals have for their teachers and, most importantly, for their kids. I think Keri and Tamara are these examples of why we care so much about school principals. So thank you to you both for what you’ve done this year. I know every year you do so much for your kids, and I know this year I can imagine your campuses are … You’ve really delivered a lot for them, and I hope you get to, at some point, put your feet up and take a nap and take a mini-break, but really appreciate all you’ve done. Andy, thank you so much for joining us for this conversation, and we’ll be able to talk to you all soon.