On March 13, Claudia Ramírez returned to El Salvador from a trip to Germany. On her arrival, she was required by the Salvadoran government to enter a 30-day quarantine in a government-run facility.

Through our Central America Prosperity Project (CAPP), the George W. Bush Institute has been working closely with a network of respected thought leaders from a wide variety of professional, political, and personal backgrounds to develop proposals for pro-growth economic policy reforms. One of the members of that network is Claudia Ramírez, a journalist and editorialist with La Prensa Gráfica, one of the largest-circulation newspapers in El Salvador. Ramírez recounts her experience during a 30-day government mandated quarantine.

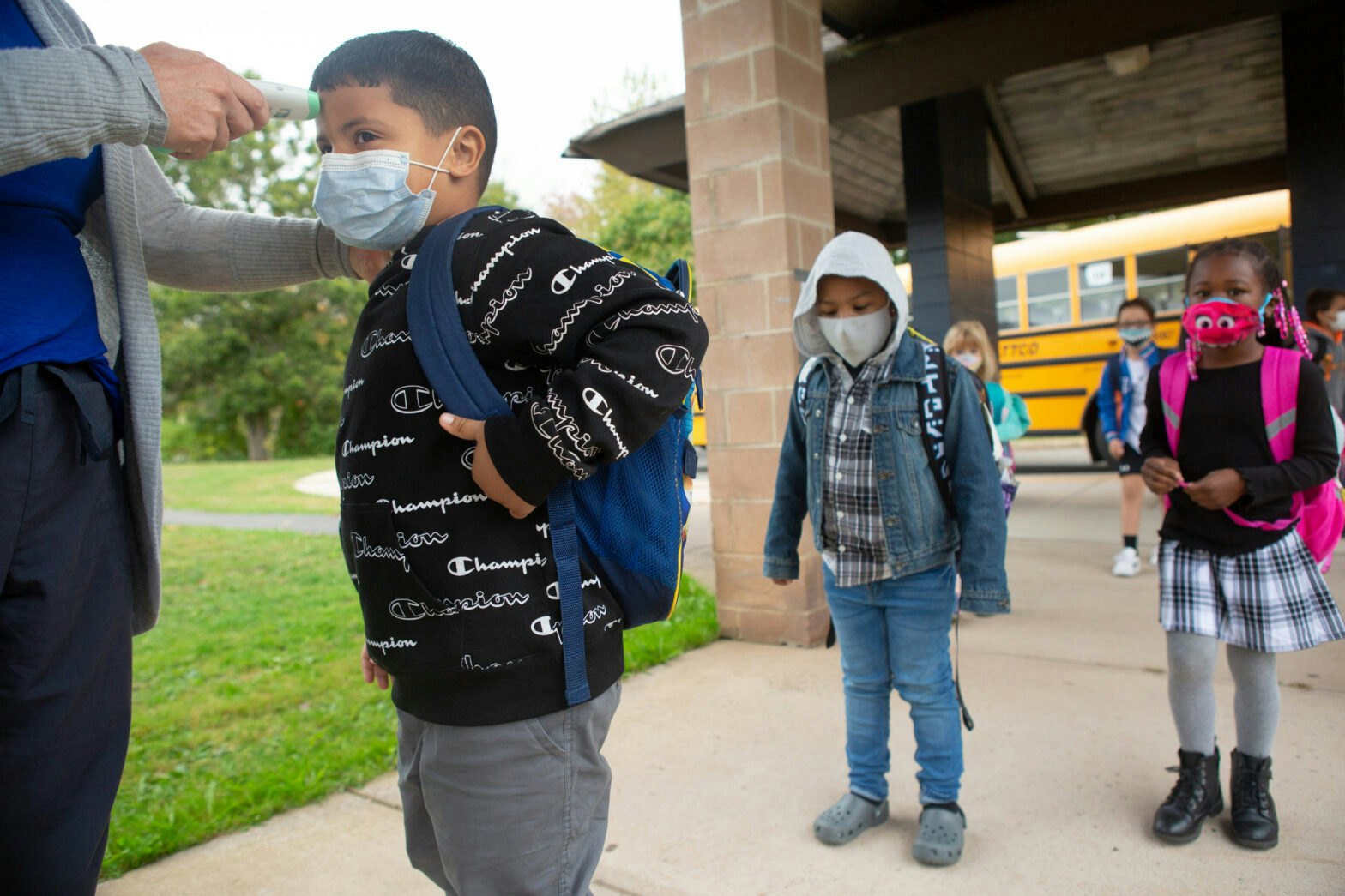

Central America has a precarious health system. In an attempt to avoid the collapse of its health network by COVID-19 infections, on March 11 El Salvador’s government instituted a mandated quarantine on all travelers arriving at the international airport.

On March 13, I landed in San Salvador from Germany. I was visiting the German foundation Friedrich Naumann to learn about migration— one of the central themes of the Bush Institute’s Central America Prosperity Project. Now, I am one of the 4,098 Salvadorans housed among the 91 quarantine centers.

As of writing this article, El Salvador has 32 confirmed cases of COVID -19, and, of these, 28 have been detected in the containment centers. There has also been one death reported.

When the government instituted the mandated quarantine, there were no Epidemiology doctors testing the passengers for COVID-19 and guiding us to our place of refuge. I was sent to El Salvador’s Olympic Village, a government-run housing facility for student athletes from the countryside who come to the capital for competitions, in the municipality of Ayutuxtepeque, a suburb of San Salvador. There were 325 people in the village and the conditions were very poor.

We arrived to the village via three buses with 30 people, men and women, on each bus. We were separated based on gender, and I was put in a room with 13 women, seven bunk beds, and no bedding. The women came from all different areas: the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, and Germany, among others.

While the containment measures appear to be working, it has also made quarantine centers the main source of contagion. In addition, the country is not conducting massive tests and the criteria under which testing is performed are not clear. For example, in a small hotel in Chalatenango, a hilly region in the north, along the border with Honduras, 108 people are being quarantined, but only 19 have been tested.

Thirty-six hours after I entered the Olympic Village, I was transferred to a smaller hostel with seven women. I am still at this hostel and completely isolated. I am forbidden from leaving my room, even though I have been social distancing. Only two tests have been performed at the hostel and results have not been shared. As we did not see anyone being transferred to the hospital, we believe the tests were negative.

As I write this, it is day 18 of my quarantine. I have not developed any symptoms and I have not been tested. Despite the World Health Organization recommending a 14 day quarantine, I am being held at the hostel for 12 more days—my thinking is the government is waiting to see if I have contracted anything from the overcrowded quarantine facilities.

In El Salvador, there are many requesting that the more than 4,000 people in quarantine complete 14 or 21 days of isolation, be tested for COVID-19, and if negative released from quarantine. But there is still no answer from the government. This move would take great economic and social pressure off the government, which must pay for food and lodging.

For now, I wait for my quarantine to end.