The United States is uniquely positioned through its political and economic might to address the conditions that foster displacement and extremism, and lead humanitarian efforts to combat them.

About 26 million people around the world have been forced from their homes and live as refugees in foreign countries. That number has surged in recent years and has coincided with the Trump Administration’s policy of drastically reducing the cap on refugees admitted into the United States — a decision that broke with previous administrations.

Historically, the United States has answered the call to help our global neighbors through foreign-aid initiatives that alleviate human suffering such as the Marshall Plan, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, and civil society organizations like Catholic Relief Services. This generosity has also manifested through a tradition of welcoming refugees into the country — more than 3 million since 1980.

Why does this humanitarian work matter to the United States? We know that instability, despair, injustice, and oppression lead to forced migration and breed conditions of extremism. From the rise of the Axis powers to the Sept. 11 attacks to Syria’s civil war, extremism can leach through borders to harm multiple countries and regions — including our own. The United States is uniquely positioned through its political and economic might to address the conditions that foster displacement and extremism, and lead humanitarian efforts to combat them. Beyond that, Washington can serve as a moral example to encourage democratic allies wrestling with their own challenges to do the same.

The Refugee Act of 1980

The United States did not have a consistent policy for welcoming refugees before 1980. Through the carnage of World War II and much of the Cold War, the United States offered such support on an ad hoc basis (and not always admirably). Examples include a single group of European Jews escaping Nazi tyranny, Soviet dissidents, Cubans fleeing the Castro regime, and 125,000 Vietnamese evacuated and sponsored for resettlement in the United States in the fallout from the Vietnam War.

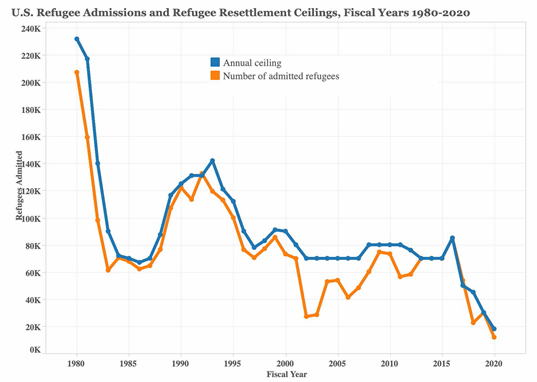

This approach changed when, drawing from the United Nations Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees — which defines displaced people as “unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion” — Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980. The new statute was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter. It set up a more orderly system by which the United States would admit refugees for resettlement based on an annual ceiling as determined by the President and Congress.

Since 1980, groups of refugees have been resettled across the United States, bringing their talents, traditions, cuisine, and more to enrich our country. For instance, Cubans and Venezuelans escaped tyranny in their home countries and continue to make South Florida a vibrant cultural hub. The Lost Boys and Girls of South Sudan escaped incredible violence and resettled in places like Dallas, where they have become productive members of the community. And thanks to the North Korean Human Rights Act that passed in 2004 — and was renewed under the Obama and Trump Administrations — a special pathway was created for North Koreans who escaped their homeland to enjoy freedom in the United States.

This policy should be a source of pride for Americans. It reflects our country’s ability to help those who are most vulnerable and demonstrates a generous American spirit committed to those who are in great need. Moreover, it undermines the credibility of the governments of their countries of origin, who must watch as their former oppressed citizens come to this country and thrive and prosper in freedom.

The Falling Refugee Ceiling and Confronting Myths

In 2017, the Trump Administration dramatically altered course on refugee admissions. From 1980 to 2016, the average “ceiling” determined by U.S. presidents was just under 96,000 annually. During that time, the lowest cap on record was 67,000 in 1986. However, the average annual ceiling plummeted to 35,750 from 2017 to 2020. The Trump Administration set historically low admission caps each year – starting at 50,000 in 2017 and culminating with 18,000 in 2020. Moreover, the final refugee determination of the Trump presidency, issued in October for fiscal year 2021, set the cap at another historic low of 15,000.

None of that is to suggest the United States should take a “we’ve always done it this way, therefore we should always do it this way” approach to its refugee admissions policy. Our leaders have adjusted the ceiling based on global realities many times over the past 40 years. However, the past several years have presented a time of historically great need, so it’s disappointing that the caps were set so low.

Presently, the world is reeling from record numbers of displaced people. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 1% of the earth’s population (nearly 80 million people) is displaced.

Of course, the onset of a global pandemic would constitute an understandable reason for wanting to reduce the ceiling, but most of these caps were determined before COVID-19 appeared.

Instead, the Trump Administration often pointed to national security concerns as its rationale for cutting back on refugee admissions. They included the infamous “Muslim ban” that heavily restricted visa applicants from 13 countries, many of which have considerable or vulnerable Muslim populations.

Virtually all the countries that appeared on the list suffered from insecurity due to violence, oppressive regimes, or both. For instance, Burma was added even as its Rohingya Muslim population suffered intense persecution from the military and the civilian government. In 2018, a United Nations report described the Burmese military’s use of violence, rape, torture, and “clearance operations” (the destruction of entire villages) against the Rohingya as having “genocidal intent.” Since 2017, more than 700,000 Rohingya men, women, and children have been driven from Burma.

On the surface, security can be a reasonable argument for reducing migration flows into the United States, and the issue divided American public opinion. However, the data do not support the claim that refugees threaten public safety.

A 2019 analysis from the Cato Institute calculated that the chance of an American being killed by a refugee committing a terrorist act was 1 in 3.86 billion. Since 1975, three Americans have been killed in terrorist attacks committed by refugees. And while that loss of life is tragic, it is important to note that these deaths occurred before the Refugee Act of 1980 created the stringent vetting system that exists today.

In fact, organizations like the International Rescue Committee note that “the hardest way to come to the United States is as a refugee.” Those wishing to apply must first register with the UNHCR before being selected for refugee status by the American government. From there, applicants must submit to intensive background checks by U.S. agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI. Sometimes, applicants remain in limbo for several years before being accepted.

Even if refugees are not a security threat, some Americans fear them becoming an economic burden on the country.

That myth starts to fizzle with one of the first commitments newly admitted refugees make to the United States. Refugees must agree to pay back any U.S. loans received to purchase airfare for their escape. And they do.

Upon arriving in the United States, refugees do get short-term support coordinated by nonprofits like IRC and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to help them settle and integrate into American society.

After that adjustment period, though, they must become relatively self-sufficient. Through hard work and dedication, most become productive members of their new communities. As cataloged by the National Immigration Forum, refugees contribute to the economic vitality of the places where they settle and

the nation overall. This includes contributing billions to national and local economies, filling needed jobs across various industries, developing desirable skills for employers, buying houses and laying down roots, and starting their own businesses and entrepreneurial endeavors that serve their communities.

For all these reasons, scaling back U.S. refugee admissions should be concerning to Americans. This is particularly true if any such determination were tied to a refugee’s country or religion as could be inferred from the so-called Muslim Ban restrictions. That would betray our country’s values of expanding liberty, providing opportunity, demonstrating compassion, and promoting justice — not to mention defending freedom of conscience.

Recommendations

Efforts to chart a new course on U.S. refugee policy are already underway in Washington. On Jan. 20, the Biden Administration released its proposal for immigration reform and President Biden issued a series of executive orders that reversed several Trump-era policies, including the restrictions placed on refugees from the “Muslim Ban” countries. As the nation pivots, the George W. Bush Institute makes the following recommendations:

Opinion leaders should inspire, inform, and advocate for a more robust and welcoming refugee policy

This is largely a matter of utilizing more optimistic rhetoric and tone. Our country’s founding principles should discourage our leaders — in government and all other facets of society — from engaging in fearmongering, nativism, or hate speech. In a time of increased polarization and distrust, we need leaders that tell people the truth, especially when it is difficult or unpopular, about unfounded myths that fuel xenophobia against refugees.

Instead, leaders should remind people of America’s generous spirit and its traditional role as a global leader in supporting refugees. They can do this and alleviate constituent concerns by explaining that refugees are not a security threat to Americans — as decades of evidence show. They can point out that the vetting system for refugees is both rigorous and thorough. Finally, they can share how studies demonstrate that refugees bolster their communities economically.

State and local leaders should lead the charge in adopting such language when it comes to refugee resettlement in the United States. Their cities and towns are the foundation upon which refugees build new lives and they are the primary beneficiaries of the rewards that refugees bring. Stories of refugees enriching their adopted homes can be found across the country. There are places like Lewiston, Maine, where — despite not always being a fairy tale — Somali migrants have helped revitalize a dying mill town.

Lastly, our leaders should avoid conflating a welcome to refugees with disregard for borders and national security. Foremost because that conflation is simply untrue, but also because it feeds outlandish narratives that legal migration is harmful to our country.

Congress must exercise its constitutional obligation to provide oversight of U.S. policy on refugees

According to a report, the Trump Administration mostly sidestepped Congress’ legal obligation to consult on the president’s annual refugee determination as called for by the Refugee Act of 1980. Going forward, it is a precedent that Congress should take special care to discourage in order to uphold the law and its authority as a central pillar of U.S. government.

In doing so, Congress should reassert its consultative role in the annual refugee determination: Members and committees should issue press releases highlighting their obligations, submit letters to the White House and State Department outlining their expectations, and hold hearings with U.S.-based resettlement organizations and refugee communities to further assess needs.

The executive branch should utilize a more welcoming policy toward refugees as an opportunity to re-establish U.S. global leadership and rally democratic allies

This work has already started with the Biden executive order on refugees. The urgency with which the order was issued was encouraging, but more must be done over the next several months and years.

The Biden Administration, in consultation with Congress, should work to restore refugee admission ceilings to pre-Trump levels. Given the record-high numbers of displaced persons and refugees globally, it might also consider increasing caps above historical averages. At the same time, the administration should expand the capacity of refugee-vetting infrastructure to help overcome existing backlogs.

Demonstrating such leadership and compassion would accomplish good on several fronts:

First, it would signal to our democratic allies in NATO, Africa, Asia, Latin America, and elsewhere that the United States is re-engaging with the world. Moreover, the Biden Administration should coordinate with these allies and where necessary use its own increasing commitments to resettle refugees to leverage similar shows of generosity from those nations.

Second, increasing U.S. commitments would lessen the burden on other host countries that may lack the adequate resources or infrastructure to care for refugee populations. Additionally, relieving that burden may reduce the risk of further destabilizing potentially fragile conditions in those host countries and regions.

Finally, it could boost America’s declining reputation overseas. Improving our relationships would foster greater trust and the necessary social capital to better promote our country’s economic, security, and diplomatic interests internationally.

Congress and the administration should prioritize international democracy support and other foreign assistance that address the root causes of forced migration

Ultimately, the best way to prevent forced migration and displacement is to eliminate its root causes: poverty, disease, oppression, violence (including gender-based), corruption, and, increasingly, climate change. And the United States is uniquely positioned with its political and economic might to lead such efforts.

The Biden Administration has already proposed addressing these causes as part of its immigration policy. However, the Biden Administration and Congress must continue to make the case to the American people that foreign aid — democracy support, health care, infrastructure, economic development, and education reform — is crucial to this strategy, and provide the resources to support it.

Strengthening democracy abroad must not be overlooked as a critical piece of this assistance. Our leaders should ensure the continued funding of and reliance upon organizations like the International Republican Institute, the National Democratic Institute, the Center for International Private Enterprise, and the Solidarity Center that specialize in working with foreign governments and citizens to promote good governance at the national and local levels. Their programming includes vital services like developing more transparent and responsive institutions, building issue-based political parties, engaging businesses in the democratic process, and enhancing the capacity of civil society.

After all, democracy is the only system of government that strives to protect civil liberties and minority rights, encourages the entrepreneurial spirit, fosters responsive political institutions and the rule of law, and provides a marketplace for competing and diverse ideas. Most importantly, it enshrines nonviolent mechanisms for making the government accountable to the people and improving the system.

American society should encourage the nonprofit and private sectors to develop programs that help refugees integrate and become contributing members of society

Supporting refugees is not government’s work alone. Already, nonprofits are responsible for coordinating refugee resettlement, but there’s room for more organizations and businesses to contribute and innovate in this space.

Programs that are tailored to specific areas of need can be extremely valuable in the assimilation process. For example, the Bush Institute established a scholarship program for North Korean refugees who resettled in the United States.

In doing so, the Bush Institute conducted needs assessment studies on North Korean refugee communities that found many of the refugees were in low-level jobs with little chance of improving their situation. They wanted the opportunity to address this gap through education but faced too many economic difficulties.

Now, North Korean refugees can apply for this scholarship to pursue postsecondary degrees, English- language classes, or vocational programs. The awards can be put toward tuition, fees, books, or on- campus housing.

Nonprofits and businesses that are not currently assisting refugees should consider developing similar programming that provides refugees opportunities to learn new skills, create better lives, and integrate into their communities. Such support could range from leadership development, advanced English- language classes, civic and citizenship education, basic household management (like paying bills and getting health insurance), or public speaking and advocacy training.

For nonprofits, there could be ample opportunities to tie such efforts to existing programmatic themes and objectives. For businesses, it fits well into corporate social responsibility efforts that strive to improve the communities in which they are based.

CONCLUSION

With a new administration and Congress ready to govern, the time is right to reignite the humanitarianism and generosity of spirit that has made the United States a global leader on supporting refugees.