The winding road to justice

People’s fears about the state of the country are intensified by the tendency to see history as linear. But the fight for racial justice shows that bad times sometimes lead to breakthroughs.

Two marines walk in Harlem, New York in 1943. (Photo by Roger Smith/Anthony Potter Collection/Getty Images)

Two marines walk in Harlem, New York in 1943. (Photo by Roger Smith/Anthony Potter Collection/Getty Images)

Many Americans today are worried about the health and future of our democracy, and with reason. U.S. politics are polarized and increasingly tribal, elected officials who once pledged to uphold the Constitution seek ways to work around the law, and citizens are increasingly resorting to violence in the attempt to steer government in the direction they favor. It’s no wonder that many Americans now question the ability of our democratic institutions to respond to the will of the majority – or to function at all.

This anxiety is exacerbated by a tendency to think that history is linear – that it proceeds in one direction. When we feel optimistic, we often imagine that victory begets victory, that the trend of history is toward progress, and that the future is always brighter than the past. When things look gloomy, we worry that it’s all downhill from here.

But history does not move in a straight line, especially when it comes to politics. American political history looks more like a series of mountain switchbacks than a flat Midwestern highway. That truth becomes especially evident when you consider the history of the post-Civil War South. For that reason, the period is one that pessimistic Americans should think about today. It offers two powerful and hopeful reminders that all of us should bear in mind. The first is that today isn’t the worst moment in our country’s history, especially when you consider the experience of nonwhite Americans. And the second is that things can, do, and, in that case, did get better – indeed, the bad times helped pave the way to the better days that followed.

Pearl Harbor and Jim Crow

The violent storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, may have been unprecedented at the federal level, but it bore a striking resemblance to events that occurred all across the American South in the late 19th century, when White Democrats attacked local seats of government, overturned democratically elected racially mixed state and municipal governments, wrested political power from White and Black Republicans through violence and election fraud, and then disenfranchised the latter group.

In the 1880s, more than two-thirds of adult Southern men, Black and White, voted. That proportion rose to nearly three-quarters in the 1890s, an era of great fluidity in American politics. By the early 1900s, however, fewer than one man in three was voting in Southern elections, thanks to the imposition of poll taxes, literacy tests, violent voter intimidation, and fraud. Blacks were relegated to the lowest ranks of the economy, their educational opportunities were circumscribed, and their social interactions were carefully policed. Did this represent progress? If you were a White Southern Democrat invested in one-party minority rule, then yes. If you were anyone else, not so much.

This bleak state of affairs continued in the South right up until World War II, and it didn’t seem to bother many Whites at the time; in fact, few even seemed to notice. According to a poll conducted by the National Opinion Research Center in 1942, about two-thirds of White Americans said they thought Black Americans were basically happy with the way things were; only a quarter said they thought Blacks were dissatisfied.

In the 1880s, more than two-thirds of adult Southern men, Black and White, voted, but by the early 1900s, fewer than one in three did.

By 1944, however, those numbers had flipped. What happened? The answer is that, over the course of the war, White Americans were forced to confront the reality of Black subjugation. They saw it firsthand and they read about it in the papers – experiences that opened their eyes to the horrors of White supremacy in their own country, even as the United States was fighting racist fascists abroad. In a striking parallel to today, Americans across the racial spectrum began asking whether their country was fundamentally flawed and how – indeed, whether – it could be fixed.

Early in the war, many Black Americans recognized that the conflict would fundamentally change the United States. As the poet Langston Hughes wrote in 1942, “Pearl Harbor put Jim Crow on the run / That Crow can’t fight for Democracy / And be the same old Crow he used to be.”

Southern White supremacists feared the same thing and responded accordingly by enforcing Jim Crow boundaries in public spaces and transportation and reacting violently to any perceived “acting up” by Black men. By May 1942, 14 Black men in uniform had been killed by civilian police in communities adjacent to military camps. And by the end of the war, the country had suffered six civilian race riots, more than 20 military riots and mutinies, and between 40 and 75 lynchings (the number is imprecise because the definition of “lynching” changed over time). As Howard Donovan Queen, a Black Army officer who eventually rose to the rank of colonel, recalled years later, “The Negro soldier’s first taste of warfare in World War II was on army posts right here in his own country.”

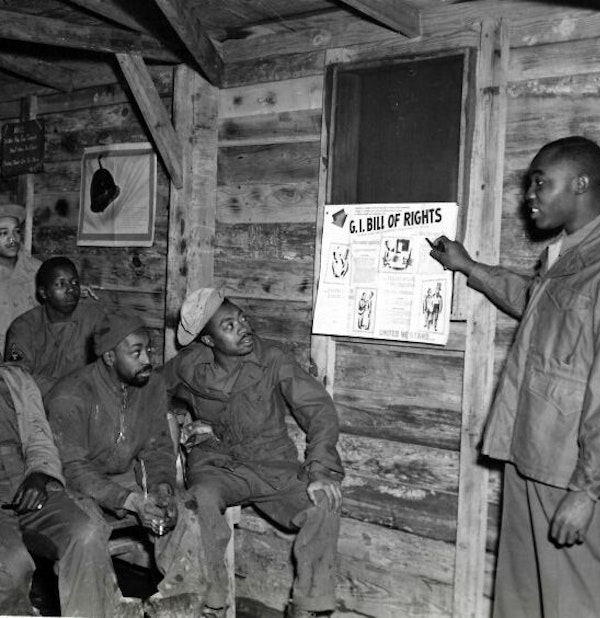

A sergeant explains the G.I. Bill to fellow soldiers in Italy in 1944. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A sergeant explains the G.I. Bill to fellow soldiers in Italy in 1944. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Veterans go to war

A few years later, the Black American soldiers who returned home from serving in the war had been deeply changed by their experiences abroad. They had fought, and many had died, for their country, and they expected something in return. “I carried myself in a different way after I came back, and people could tell I had been in the service,” remembered Fred Hurns, a medic in the 3rd Army Division.

Not every Black soldier was jolted into militant opposition to Jim Crow, but many were, and they willingly enlisted in the struggle against White supremacy when they returned. Challenging segregation could prove deadly, however. As they had during Reconstruction and after the first World War, White Southerners responded to Black demands for equality with pitiless violence. During the summer of 1946, Southern Whites blinded, castrated, and murdered 56 Black Americans, many of them veterans. Local law enforcement agencies often lent a hand, engaging in an orgy of official violence that was extreme even by Southern standards. When ex-Marine Timothy Hood removed the racial divider from a segregated streetcar in Brighton, Alabama, he was shot five times by the conductor, arrested, jailed, and then executed by the local chief of police. From Tennessee to South Carolina, returning Black veterans encountered what New York Rep. Vito Marcantonio, of the American Labor Party, termed “a mounting campaign of terror … [designed] to re-subjugate the Negro GI.” One Black veteran described what was happening to him and his comrades more simply. As he told Oliver Harrington, the NAACP’s Director of Public Relations, “They’re exterminating us.”

White Americans would come to agree that men who ‘faced bullets overseas deserve ballots at home.’

But even the most gruesome violence couldn’t block progress entirely. In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Smith v. Allwright that the South’s system of racially restrictive primary elections violated the 15th Amendment. Important as it was, the decision did not on its own herald a new era of Black enfranchisement; achieving that would take another 20 years, mass protests, a federal voting rights act, and a constitutional amendment forbidding poll taxes. But the court’s ruling was a sign that the war had changed the attitude of many White Americans toward racism, and that the ground was shifting. By the end of the war, a majority of White Americans would agree with the sentiment that men “who faced bullets overseas deserve ballots at home,” and that Black disenfranchisement reflected “the hateful ideologies” that the country had fought against in Europe and Asia.

In 1945 and 1946, interracial labor unions and civil rights organizations joined hands in a full-blown campaign to expand Black political power. Henry Lee Moon, a leader of the NAACP and a field organizer for the Congress of Industrial Organizations, reported that everywhere he went in the South, he found “a politically inspired people.” In the spring of 1946, a 17-day voter registration drive in Savannah, Georgia increased the number of Black voters there from 8,000 to 20,000. Despite the obstructive tactics of registrars in Virginia, meanwhile – a state where only 11% of all eligible voters were registered – 40,000 new Black voters were added to the roster in 1946 alone. In the spring of that year, the U.S. solicitor general announced that the Justice Department would prosecute any state or party official who attempted to prevent a person from voting on the grounds of race. All in all, an estimated 600,000 Black Southerners registered to vote in 1946, triple the estimated number in 1940.

Voters line up outside polling station in Cobb County, Georgia in 1946. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Voters line up outside polling station in Cobb County, Georgia in 1946. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

A small but significant number of White veterans also joined the struggle for a more democratic South. Some joined existing organizations dedicated to political and economic change, while others organized chapters of new associations like the American Veterans Committee, a racially integrated alternative to the segregated American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars. These White vets demanded honest elections and an end to political corruption. In Arkansas, former Marine Lt. Col. Sid McMath led a voter revolt among ex-GIs that won a handful of county offices in 1946, the mayoralty of Hot Springs in 1947, and the governor’s seat in 1948. Veterans in Athens, Tennessee, organized a similar project and nominated a slate of officers. When the Democrats stole numerous ballot boxes on Election Day, some 2,000 disciplined ex-servicemen armed with pistols, rifles, hand grenades, dynamite, and a .50-caliber machine gun besieged the jail where the ballots were being held and recovered the boxes. Their candidates also won the election. And in Texas, future congressman Jim Wright supported abolition of the poll tax and the admission of Black students to the University of Texas School of Law.

Some could no longer stomach the discrepancy between America’s professed values and the reality of segregation.

White supporters of Black suffrage had a variety of motives. Some could no longer stomach the discrepancy between America’s professed values of freedom and equality, for which so many of their comrades had given their lives, and the reality of segregation. Others were convinced by the argument that racial discrimination undermined America’s global mission to demonstrate the virtues of democracy to a shattered world. Still others had commanded Black troops during the war and through them had experienced the conditions of life on the wrong side of the color line. As Harold Fleming, who headed a regional racial reform organization in the 1950s, recalled, “The nearest thing you could be in the Army to being Black was to be a company officer with Black troops, because you lived and operated under the same circumstances they did, and they got crapped all over.” Fleming’s experience did not transform him into an activist right away, but it did awaken him to the structural bases of Jim Crow. As he explained years later, “It wasn’t that I came to love Negroes; it was that I came to despise the system that did this.” It may be an exaggeration to argue that Hitler had given racism a bad name, as some have suggested. But it is true that the war led many White Southerners to reevaluate the harsh realities of American White supremacy when they returned home.

If it didn’t happen to kill you, one of George Orwell’s characters once remarked, war was bound to start you thinking. The remarkable attitude shift among White Americans registered by the National Opinion Research Center poll in 1944 – which led to the widespread recognition that Black Americans were unhappy with their circumstances, and understandably so – grew out of several forces. One probably was the revelation of Nazi atrocities. But another was the effect of Black activism. By refusing to back down in the face of horrific violence, Black veterans inspired their fellow citizens. And they and their White allies became the leading edge of the midcentury Civil Rights Movement, particularly the fight for the vote. Their goals were not accomplished in a day, but change always starts somewhere.

Bending toward justice

As unnerving as the state of contemporary American politics has become, perspective matters. Broaden the historical lens and it becomes clear that, for all its flaws, the democratic process today is working much better for many Americans than at any time in the past. Women could not vote in federal elections before 1920. Racial minorities, especially but not exclusively in the South, were overwhelmingly disenfranchised before World War II. Young adults old enough to be drafted could not vote until 1971. All of that is profoundly different today.

None of those changes happened by accident, and none are immune to reversal – through contemporary efforts to limit suffrage using restrictive voting laws and through extralegal assaults on the democratic process. But the history of Black enfranchisement during and after World War II, and the growing recognition among White Americans that discrimination affected everyone, should give us all hope. Among other things, it demonstrates a powerful attribute shared by millions of Americans then and now: the capacity to change our minds as circumstances change around us.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.