Interview

A correction is coming: A conversation with President George W. Bush

The former president weighs in on the state of American democracy, why he’s still an optimist, and how to fix the country’s politics.

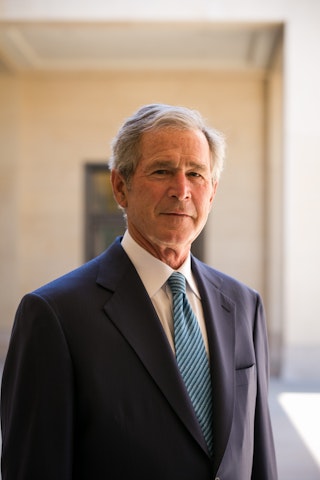

President George W. Bush speaks at the Bush Center in Dallas, Texas on October 11, 2019.

President George W. Bush speaks at the Bush Center in Dallas, Texas on October 11, 2019.

A few weeks ago, in an exclusive interview with The Catalyst, President George W. Bush sat down with Jonathan Tepperman, the journal’s Editor-in-Chief, and Associate Editor David Kagan to share his thoughts on the state of the union, how to improve the functioning of the U.S. government, and why Americans should, even now, remain hopeful. Their conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

A lot of Americans are nervous about the state of the country and the direction in which we’re headed. You are famous for being an optimist. What do you say to them?

This is not the first time that we have had a political crisis that made people doubt the future. If people are worried today, my first suggestion is that they read about the Civil War, or about the 1920s, when we had a zero-immigration policy, or when we had Alien and Sedition Acts that said if you criticize the government, you’ll be put in jail. They should read about the Great Depression, and the isolationist period when we watched Adolf Hitler begin to march across Europe and did nothing. Or they should pay attention to the late 1960s.

One of the things that was common to all those periods is that, thanks to our institutions, American democracy was able to self-correct. And the correction period is beginning. People are sick and tired of loud, angry politics. They want better from their leaders. Plus, they recognize that we’re way too old at the top. It may or may not happen during this electoral cycle, but eventually, young leadership will show up, which will be much more inspirational to the American people. We’ve had inspirational leaders in the past who have had the capacity to take a gloomy outlook and make it bright. So yes, I am an optimist, and I’m confident we’ll self-correct again.

What are the signs that the correction is already beginning?

When I talk to fairly good-sized crowds of people, what I hear is that they all recognize that we need young leadership and that we can do better in our public dialogue as a nation. They recognize that Congress is dysfunctional, that things aren’t getting done that need to get done, and they expect better from our government. People expect major problems like the border and the national debt to be addressed.

Why is so much of our political establishment so old? How did this happen?

When we were elected, President Bill Clinton and I represented generational change; we were the first baby boomers to replace the World War II generation of presidents. President Barack Obama was in between generations. But then we took a step backward with the nominees and presidents who followed. Why? I don’t know. Either there weren’t candidates who could challenge them, or the establishments in both parties were locked in.

What do you think explains the level of extremism and divisiveness in the country?

In both parties, two things come to mind. One is that, if you win your primary, you win the general election. But primaries have very small turnouts these days, with the most loyal voters. That means that you can now win an election by ginning up a small percentage of the population, sometimes with extremist rhetoric. And the only way you can get beat in a primary is if your opponent takes an even more extreme position.

When you combine that with social media, which tends to sensationalize conspiracy theories and fringe attitudes, you end up with a system where the general population doesn’t really determine the national discourse.

Does that explain why we now have one party in the thrall of a self-declared dictator, and the other party seems focused on identity politics?

Well, it’s the same phenomenon. It’s not an attempt to seriously solve problems. To me, it seems like our politics have become about self-preservation – anticipating some popular movement and either leading it or trying to head it off.

Congress is myopic in that they think in two-year time horizons: their next election. The problem is that there’s not much strategic thinking happening at the national level. That requires an active chief executive who looks beyond the moment and anticipates problems and rallies people to deal with them. Take Social Security. It’s a looming problem for young people, yet we haven’t seen a serious attempt to reform it. As a matter of fact, politicians in both parties have said, “If you touch it, I’m going to rail against you.”

Keep in mind, I tried to reform Social Security and failed miserably. I remember members of Congress saying to me, “We won’t back you.” I said, “What do you mean? I campaigned on this.” But they said, “We won’t back you, because we’re going to lose seats.” My point is that there are political rewards for not taking risks.

A lot of these same problems existed back in your day, but there wasn’t the level of hatred and demonization we see today. What changed?

I think there’s a general anger in the population, which is one of the root causes of populism. It’s easy to be angry at immigrants, and that’s been the case throughout our history. During Woodrow Wilson’s Presidency, it was said that we had “too many Jews and Italians in the country,” so therefore immigration policy was set at zero. It was a reaction to insecurity and anger in society.

We work on immigration policy here at the Bush Institute. Can the problem be fixed? Absolutely. But with a chaotic border, it’s hard to pass reforms. It’s hard to get people to understand that this is a human issue and an economic issue. You talk to small business owners who say, “I’m looking for workers.” And yet there are a lot of workers trying to get into the country right now, but there’s no system to enable them to do so.

We need to enforce the border, we need to fix the asylum system, there needs to be a guest worker program. But the situation is easy to exploit politically. And nothing will get done until we have leaders who say, “Let’s put the politics aside and focus on rational policy.”

As I’m sure you know, the percentage of foreign-born people in the United States recently reached the highest level ever. When that’s happened in the past, it’s led to extremist reactions – unless there was a smart government policy in place to deal with it.

That’s right, and there’s a void right now. When you’re angry, it’s hard to have confidence in the capacity of the United States to assimilate people. I understand the anger.

Where do you think it’s coming from?

I’m a little self-castigating in that I think bailing out Wall Street when I was president created a lot of the anger. Imagine you’re a guy paying your taxes and you don’t particularly like Wall Street to begin with. The banks created these financial instruments that nobody could understand and created a house of cards. Then housing values declined and the whole house of cards collapsed. That left me with limited options: Let it collapse and risk a depression, or give money to the banks and prevent a depression. The perception was that the elite won, but the tax-paying guys who work for a living lost.

In retrospect, do you think you could have done more to connect the importance of saving the banks to the life of the average worker?

No, because things were cratering so fast. Bear Stearns was a canary, then every weekend these big, overleveraged companies started to follow, and I was convinced that we were headed for a great depression. We had very few ways to solve it, except for a gigantic taxpayers’ fund. Now, they got their money back plus interest, but that didn’t matter politically. And then afterward there was lots of cheap money floating around, which was good for Wall Street, but wages didn’t increase. There was no focus on economic growth in the private sector. So you had stagnating wages, rich people getting richer, and people started getting angry. And those running for office at the time said, “You’re angry – I’m going to make you angrier!”

When you were governor and president, you got a lot done on a bipartisan basis. That’s less common today. Do you have any lessons for today’s leaders?

You have to start with a desire to get things done, and you have to have an agenda. Then you have to reach out to people and convince them of the importance of working together. It takes a lot of time and a lot of effort. If you have the desire, the president has a lot of tools at his disposal. But it takes a lot of courtship.

When we passed No Child Left Behind, which at the time was one of the great education reform packages, we got Sen. Ted Kennedy and Rep. George Miller – both Democrats – on board. But it required ignoring labels and just saying, “Yeah, I’m going to work with Ted Kennedy because he can get something done in the Senate.”

It’s like foreign policy. The president’s got to spend an inordinate amount of time building and strengthening alliances, because a country without alliances is an isolated country. But to do that, you’ve got to spend a lot of time on the phone, and that means talking to the leaders of small countries, not just big ones. It requires energy and youth, because it’s a lot of work.

Are you worried about the growing isolationism in both parties?

Yes, because it’s related to populism. The three isms of isolationism, protectionism, and nativism are all related, and I spoke about two of them in my 2006 State of the Union address, because I felt them coming.

Are isolationism and our other political problems affecting America’s ability to lead internationally?

Yes, but that can be mitigated by a president who works to strengthen our alliances. Listen, we’ve got great alliances with countries with shared values. I think the rest of the world knows that America will eventually deal with our problems. The question is whether or not America cares about jointly solving international problems.

Do you worry other countries have lost faith in the durability of U.S. commitments?

I think pulling out of Afghanistan shook the world’s confidence in America’s capacity to honor commitments – a commitment, in that case, to protect women and children. Both presidents subsequent to President Obama wanted to get out of Afghanistan, but there was no explanation of what would happen if we did. I never understood why people felt we needed to get out of Afghanistan, particularly since our military footprint was not very big. And because history has proven that a continued U.S. presence can help solidify democracy. History teaches that democracies don’t war with one another.

One of my favorite memories is about a speech I gave in South Korea to 50,000 Christians in 2010. As I was sitting on the stage, I looked at that sea of faces who were able to worship and congregate freely. And I started thinking about President Harry Truman, who had faith that democracy could take hold in a part of the world that needed it. I thought about the U.S. and other soldiers who fought in the Korean conflict, and their sacrifices. And I thought about what the lives of those 50,000 people in the audience would be like had America and other UN members not made the decision that freedom was important.

And then I thought about the American people. Do they understand this history? South Korea today is a huge trading partner of ours, and a strong ally in this day and age of an ascendent China. And yet that lesson, about the value of U.S. engagement with South Korea and countries like it around the world, hasn’t really been taught very effectively. Now, there was huge impatience with South Korea for a while, because its government didn’t satisfy our democratic standards. And I agree with that; I think the United States ought to urge people to honor freedom of the press and of religion and the right to open dialogue. But eventually all those things came to South Korea.

Why is U.S. public support for Ukraine declining?

Well, first of all, we’ve got politicians who are anxious to use Ukraine as an issue. But somebody needs to explain what the world will look like if [Russian President Vladimir] Putin prevails and then turns to Poland and the Baltic states, for example. That case needs to be made clearly. And I think a lot of Americans do already understand that.

The president also has to make the case for American leadership, and that starts with having confidence in the goodness of America. You have to believe in our goodness in order to make the case that we need to be engaged with the world.

You keep alluding to the need for American leadership, and you’ve mentioned great leaders we’ve had in the past. As you’ve also said, the United States has experienced many crises before. But in many of those cases, we were lucky enough to have a Washington, a Lincoln, or a Roosevelt to guide us out of them.

It’s going to happen again.

Why hasn’t it happened already?

Because the old people are clogging the system. It’s going to require a younger leader. But I’m confident it’s going to happen. I don’t think I’m naive. I remember Ronald Reagan. He may be taken for granted now. At one point, he was seen as an actor buffoon. Yet he had the capacity to light up our confidence. He could say, “Follow me, and the world is going to get better,” and people did. Will somebody else show up and do that again? Yes.

What do you think ordinary Americans can do to improve our politics in the meantime?

They can love a neighbor like they’d like to be loved themselves. They can try to find truth. Everybody’s locked down right now, and if you’re seen compromising with the other side, you’re viewed as someone who lacks conviction. That will change. But little will break the deadlock until we have new leaders.

And in the meantime, our institutions will do their job. Our institutions were under assault on Jan. 6, and they held. Our institutions have been threatened in the past, and they’ve held. The ship of state may list, but it’s not going to sink. Democracy will self-correct. The office of the president is more important than the occupant, which allows all of us with our strengths and weaknesses to come and go. And the ship of state sails on.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.