Building Opportunity for Generations

Immigrants come to the United States in search of a better life. They sacrifice the world that they know for a world of unknown challenge, but also opportunity — not just for themselves, but for their children who they want to lead lives with less hardship.

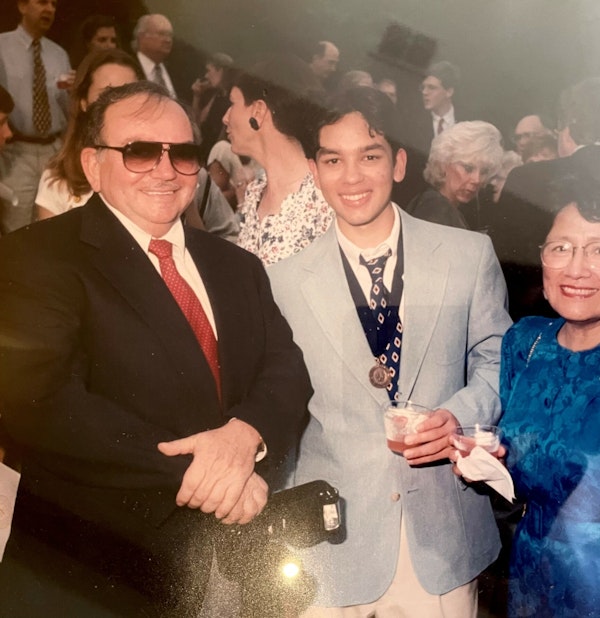

(L-R) Kalman, Andrew, and Esther Kaufmann at a high school awards ceremony in 1996. (Brad Bradley / Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

(L-R) Kalman, Andrew, and Esther Kaufmann at a high school awards ceremony in 1996. (Brad Bradley / Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

You can be anything you want to be when you grow up.”

I have vague memories of my mom telling me this when I was young enough that she was still reading books to me. And she kept repeating it year after year, through high school, when — of course — I was certain that I had already grown up.

Frankly, I got kind of tired of hearing it. “I know, I know. I heard you the first 5,000 times. You don’t have to keep repeating it.” I wish I could say that was my internal monologue, but I probably said it out loud, too. The wisdom of teenagers knows no bounds.

It would be years before I truly appreciated the phrase. I really could be anything I wanted when I grew up: I’d been given a safe and loving home where my biggest responsibilities were to just be a kid and do my homework. And I’d been given the best education my parents could find.

I didn’t realize that those things that seemed so basic — that to this day I have to remind myself to never take for granted — were gifts that culminated from decades of struggle spanning three continents. And that everything I have is because of the bravery, determination, sacrifice, and endless love of two immigrants from opposite sides of the world with one thing in common: They were willing to leave everything they knew to follow their dream of a better life in America.

In search of freedom and opportunity

Opportunity didn’t come knocking to poverty-ridden Peru and Communist-occupied Hungary in the 1950s and 1960s.

My mother, Esther Pinedo, was born in 1939 in Aco, a village in the Andes Mountains in Peru. Like so many born into poverty, her education was the furthest thing from her mind. She bounced between Aco and the capital, Lima, working to help support her family – meaning her formal schooling ended when she was 13 years old. Her education came not from classrooms but from sewing and cleaning houses for a pittance.

As her childhood turned to her teen years, and her teen years to her 20s, she was working hard but true opportunity was nowhere to be found. Wages were just enough to live off. But she was communicating through the mail with a friend of hers who had fled Peru for America and liked what she was hearing. This was her kind of place — a country that let people create their own opportunity.

After years of dreaming of owning her own home, Esther Kaufmann was able to bring her son home to her -- and his -- first home. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

After years of dreaming of owning her own home, Esther Kaufmann was able to bring her son home to her -- and his -- first home. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

Thanks to her friend, she was able to find a sponsor in the U.S. to help her enter with a work visa. She found steady work as a live-in maid, saving nearly every penny she earned since she had few living expenses. And through years of saving, she built up enough of a nest egg to buy her own parcel of America with a modest house in North Dallas – that I came home to when I was born.

Of course, she had to meet my father, Kalman Kaufmann, first. He was born in 1940 in Ajkarendek, a rural village outside of Ajka in Hungary. His father was a tailor by trade, and while his family didn’t have much, he was able to attend school. Unfortunately, school wasn’t what he had hoped: after the Communist takeover of Hungary in 1949, the Soviet worldview (and Russian language lessons) took over the curriculum. Meanwhile, his family’s freedoms disappeared: his father was forced to abandon his tailor business to work in the mines. Information from the outside world was strictly forbidden.

His family had a contraband radio, though — they would huddle in the closet to secretly listen to news of the world. And in 1956, he listened jubilantly as word came through Radio Free Europe that the Hungarians in the capital city had fought the Russians and driven them back. He couldn’t believe it — freedom was coming.

But the Russian forces were just regrouping, and not long after quickly crushed the resistance, killing 2,500 Hungarians in days. The small Hungarian revolutionists never had a chance. And my dad realized his life in Hungary would be one of fear, poverty, and lack of freedom — and that was the best-case scenario. Russian forces were arresting and sending to camps revolutionists and sympathizers. But, through Radio Free Europe, he had been hearing about America — where you can start a business and keep its earnings, not give it all to the state.

My dad was 16 at this point. One evening, his neighbor Michael — a 17-year-old — said he was going to America with his uncle. Without hesitating, my dad asked if he could join. Less than a day later, he had said goodbye to his family and the only home he had ever known for America. He traveled from refugee camp to refugee camp across Europe, before getting on a boat in Germany headed for the land of opportunity.

A land of hope and education

Neither of my parents spoke any English when they arrived in the U.S. They didn’t expect life in America to be easy, but they knew it was their best shot at the life they wanted to lead.

I’ve seen my father cry three times: when his father, then mother, passed away; and when he described how he felt when the fog began to clear on a cold morning in New York Harbor and he saw the Statue of Liberty from the deck of the boat that brought him to America.

Thanks to a combination of the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 and the U.S. President’s Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, my father was welcomed in America. Unfortunately, there are not many jobs for a kid who doesn’t speak English. He found jobs washing dishes at diners in New York, which quickly grew tiresome. He realized though that the U.S. military would teach skills, and, as importantly, provide American citizenship after his tour. So, my father enlisted in the Army at 18 to leave behind the life of a dishwasher; although, as he lamented, he often found himself on kitchen patrol, once again doing dishes.

Private Kalman Kaufmann in the U.S. Army in 1958. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

Private Kalman Kaufmann in the U.S. Army in 1958. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

After his tour ended in Fort Hood, Texas, my father headed back toward the East Coast, only to stop in Dallas for a night of rest. Which turned into a few nights. Which turned into finding a job in photography, thanks to the Army’s training. Which turned into setting down roots, and years later, meeting and marrying a lady named Esther.

This is where I enter the story. My parents continued working hard, and decades after arriving in the U.S., had carved out a nice little corner of the American dream: my dad had started a business and they had been smart (and lucky) with real estate.

But those were just a means to an end for what they realized was their American dream: to make sure that their kid wouldn’t have to face the same struggles they did. They realized that the American dream isn’t one that’s just their own, but it’s something that lives for generations.

They realized that the American dream isn’t one that’s just their own, but it’s something that lives for generations.

They knew that opportunity began with education, so became laser-focused on a goal: providing me the best education they could muster, the education they never had the opportunity to receive. They moved from their dream home so that I could go to better schools; they emptied their savings so I could focus on studying at SMU and graduate debt-free. They wanted me to have the head start in life they didn’t have.

Moms are always fixing their sons' hair -- even on college graduation day, December 2001. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

Moms are always fixing their sons' hair -- even on college graduation day, December 2001. (Courtesy Andrew Kaufmann)

My mother in particular often wonders what her life would have been like had she had a formal education. I once asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up, and she couldn’t really answer. She remembers that she wanted a doll, but the family couldn’t afford one.

After Communism began to fall in Europe, my dad was able to see his family again decades after he said goodbye as a 16-year-old. He tells the story of his father immediately inspecting his hands for callouses, and remarking, “Good, you haven’t had to work too hard in America.”

As I watch my parents age and their immigrant story begin to come to an end, I’m finally becoming truly grateful for the lives they led and the lessons I inherited. They were born Americans at heart, they just hadn’t gotten here yet.

I wanted to be a doctor when I grew up. Then I wanted to be an NBA point guard. Turns out that maybe I couldn’t literally be anything I wanted to be, since I also inherited my parents’ height and athletic ability. Then I wanted to be a writer. In the end, I combined a slew of interests into a career that has been — and continues to be — fulfilling. I’d like to think that I’ve even been able to give back a little to this country that welcomed two people who didn’t speak English but spoke the language of hard work.

My American dream? To make sure that I honor my parents’ journeys and their sacrifices, that I pass along their lessons to another generation, and that I make America a little better, just like they did.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article Surviving or Thriving? What It Takes for Immigrants to Succeed An Essay by Farhat Popal, Immigrant Affairs Manager for the City of San Diego

-

Next Article The Resilience of Immigrants is Rebuilding America An Essay by Rebecca Shi, Executive Director of the American Business Immigration Coalition