Transforming Lives and Creating Opportunity for At-Risk Youth

Chef Chad Houser came to a sudden realization: Not everyone has equal access to the American dream. He evolved his dream to create Café Momentum, which works to provide opportunity and break cycles of poverty.

Chad Houser (center) with participants from the Café Momentum internship program. (via Café Momentum)

Chad Houser (center) with participants from the Café Momentum internship program. (via Café Momentum)

At first, Chad Houser’s American dream was to be a successful chef and open his own award-winning restaurant. But a chance encounter with teens in the Dallas juvenile justice system shook him to his core. Today, his Café Momentum brings the dreams of at-risk youth, as well as his own, to life.

Houser talked recently with Natalie Gonnella-Platts, Director of the Bush Institute’s Women’s Initiative, about the model he has built to alter life trajectories, the change he’s driving in the Dallas community, and how he hopes to ensure every person is given a chance to succeed.

Below are excerpts from their discussion, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us a bit about your background and how you came to found Café Momentum.

I am a chef and restaurateur by trade. When I was in culinary school, I had one goal in life, and that was to own a restaurant and be the chef at that restaurant. In 2007, I had the opportunity to do so. In fact, I sold my house, took the equity out of it, took out a loan, and bought into a restaurant in the Uptown area of Dallas, called Parigi. My running joke is that, in 2007, when we were going through a huge financial crisis in this country, I thought it was a wise investment to buy into a restaurant.

But my intuitions paid off, because in my first year of ownership, business grew by almost 40 percent. D Magazine nominated me as “best up-and-coming chef” in Dallas. I was feeling like I had done it — I was being nominated for awards, and I was co-owner of a restaurant where I was the chef.

It was right at the one-year mark of ownership that I volunteered to go teach eight young men, inside a Dallas County Juvenile Detention Facility, to make ice cream for a competition that was predominantly filled with college culinary students. The moment I met these eight young men, I was simultaneously incredibly inspired by them, but also quite ashamed of myself, because I realized that I had stereotyped them before I met them, and I was wrong.

That shame led to humility, and that humility led me to spend the next several hours not teaching them to make ice cream, but more importantly, listening to them. Listening to them tell me who they really were and how they really were.

Two days later, I’m at the Dallas Farmers Market, and they’re competing against the college culinary students. One of the young men wins the whole contest, beats everyone, and he’s so excited that he’s screaming in my face, “Sir, I just love to cook! I just love to make food and give it to people and put a smile on their face.”

For me, the first thought going through my head was, “How dare you stereotype this sweet, kind, young man.” But the next thing I thought was, “I get it.” My love for cooking comes from going to my grandparents’ house every week for Sunday supper. Breaking bread together and food are more than just nurturing for your stomach; they are nurturing for your soul. He was so excited and inspired, and I was so excited and inspired.

I started driving home, and I started thinking about him going to go back to the same house, the same street, the same neighborhood, the same school, the same poverty, traumas, all of those things that are determinants and factors that have pushed him in a path to detention. I started to think about 16-year-old me and 16-year-old him.

I realized that the difference between our paths in life was dictated by choices that were made for us before we were ever born. Choices that we don’t always like to talk about, or think about, or admit, but they’re true. Things like the color of your skin, the socioeconomic class you were born into, the part of town where you’re born, the basic resources you have access to — they matter.

All the opportunity that I had been presented with over and over again in my life was not anything that I earned. It was through just my existence. Conversely, this young man, the lack of opportunity, the lack of resources that he was never given, was not something that he had deserved. It was just what it was. I remember thinking, “that’s not the world I want to live in.”

All the opportunity that I had been presented with over and over again in my life was not anything that I earned…. Conversely, this young man, the lack of opportunity, the lack of resources that he was never given, was not something that he had deserved.

So, then I had a choice. I could either turn a blind eye and continue living my comfortable, successful restaurant life. Or, I could lean into it and try to be a part of something different. Option one was not an option for me. So, I started volunteering my time working weekly in one of the juvenile facilities.

I just did a lot of listening. I listened to the staff and the supervisors, and they talk a lot about two words — consistency and stability. You listen to the youth and the stories they tell you, and the things that they’re asking for revolve around consistency and stability.

For me, that’s where the idea for Café Momentum initially originated. I asked myself, “how can I do something that provides consistency and stability for them, while also providing other things that they need?” It was the idea of building a restaurant, which is what I knew, and using it to be a consistent and stable environment and providing those resources. That was the genesis for what has now become Café Momentum.

In talking about the concept of the American dream, you were pursuing or living your version of it, and in a very monumental way, were confronted as well with the inaccessibility of the American dream for so many. Tell us more about the model behind Café Momentum and what kind of impact it’s having.

Café Momentum is a 6-year-old, award-winning restaurant. In addition, we are a 12-month paid, post-release internship for young people exiting Dallas County juvenile detention facilities. We have consistently been ranked as one of the top restaurants in Dallas since the day we opened our doors. And we take a lot of pride in that, because it proves that our staff can and will rise to whatever level of expectation is set for them, as long as we’re giving them the tools, resources, and opportunity.

Over the course of those 12 months, they end up working their way through every station in the restaurant. They will spend time being a dishwasher, a prep cook, a line cook, a bus, or a server host or hostess, and a food runner. We do that for three reasons.

Interns at work in the kitchen at Café Momentum. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

Interns at work in the kitchen at Café Momentum. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

Number one is they are beginning to learn new life skills and social skills. And they’re able to apply them and practice them, in the unique environments that each one of those stations presents. For example, one of the things that we focus on is how to disagree appropriately. Well, the way in which you would appropriately disagree with a fellow line cook in the kitchen, when you’re trying to get food out for 15 tables at once is very different than the way in which you would appropriately disagree with a customer.

The second thing they’re learning is what their strengths are and what they enjoy doing. That is a new experience for most of them and an incredibly enriching experience as well. It’s an experience that also translates outside the four walls of our restaurant, or even our industry.

I’ll give you an example. We ran a special on a Saturday night recently and we told the interns, “Whoever sells the most specials gets a free entrée at the end of the night.” Well, one young man sold us out of every single special we had in the first 45 minutes we were open. Here’s the catch, he wasn’t even waiting tables. He was a busser, and he realized that he was the first point of contact with every table because he filled the water glasses. He would walk over, fill up the water, engage in small talk, employ his sales pitch. At the end of it, he would say, “So, just let your server know I told you to order the special.” That is a skill that exceeds our industry. It can go anywhere with you.

The third thing, and maybe most important, is they are learning what it means to be a team player. I think that we all have this natural idea of what being a team player means. I’m a member of a team and this is my contribution to a team, which is important. They are learning when they’re a dishwasher, that if they don’t perform their job successfully, then they affect everyone else in the restaurant’s ability to be successful and perform their job that evening. But, maybe more important for them, is the idea that as part of a team, you actually have a team that surrounds you, and a team that’s working hard to make sure that you’re successful as well. For a lot of them, that is a first-time feeling too.

As part of a team, you actually have a team that surrounds you, and a team that’s working hard to make sure that you’re successful as well. For a lot of them, that is a first-time feeling too.

While all of that is going on, we also built out a community services center, adjacent to the restaurant. We’re not only creating stabilization; we’re helping them build a solid foundation for the rest of their lives. In our community services center, we have a case management team that goes in and works on establishing stabilization, through housing, health care, food insecurities, and so forth. We also have our own high school, where every single one of our interns, if they have not already graduated through our high school, are currently in our high school and on track to graduate. We went from a 54 percent dropout rate to 100 percent attending and/or graduating high school rate.

From a recidivism standpoint, statistically half of the youth that we work with should find themselves back in detention within 12 months, which by the way, there is a taxpayer cost to that. In fact, in the state of Texas, it costs $127,000 to lock up a juvenile, with a 50/50 chance that you’re going to do it again in 12 months.

There was a study done several years ago that shows the financial impact is between $1.7 million and $2.3 million. That doesn’t include the cost of the victim, and it doesn’t include the cost to perpetuate that cycle from generation to generation. Of the more than 1,000 youth that we’ve worked with, our last study showed that our recidivism rate was 15.2 percent, which means that I love to tell the mayor of Dallas that he owes me over $40 million, because that’s how much money we’ve saved taxpayers. It is funny tongue-in-cheek, but really that’s money that is budgeted to incarcerate youth in our county, that we can divert to something far better and far more enriching for the community.

That’s money that is budgeted to incarcerate youth in our county, that we can divert to something far better and far more enriching for the community.

The juvenile justice industry term to describe the population that we work with is “throwaway,” which is a population that they use to describe a child as if to say they are discarded. Discarded by any and all combination of home, neighborhood, community, society. For the young men and women that we work with, it becomes the scarlet letter they wear on their chest that says, “This is who I am. Not who I want to be, not who I was born to be, but who society says that I am.”

In the last 12 months, our readjudication and reconviction rate is 0 percent. A lot of that comes from the idea that we’re not just a job, and we’re not just a restaurant. We are an ecosystem of support that is designed through our restaurant and community services center to holistically address all of those issues and barriers.

We help these young people to find stabilization, and then begin to help them in foundation-building through classes like financial literacy training, helping them get their government-issued ID, setting up a bank account, sex education, and parenting classes. By the time they leave our program, they do have that solid foundation with a trajectory that’s going up for them to build the rest of their lives on.

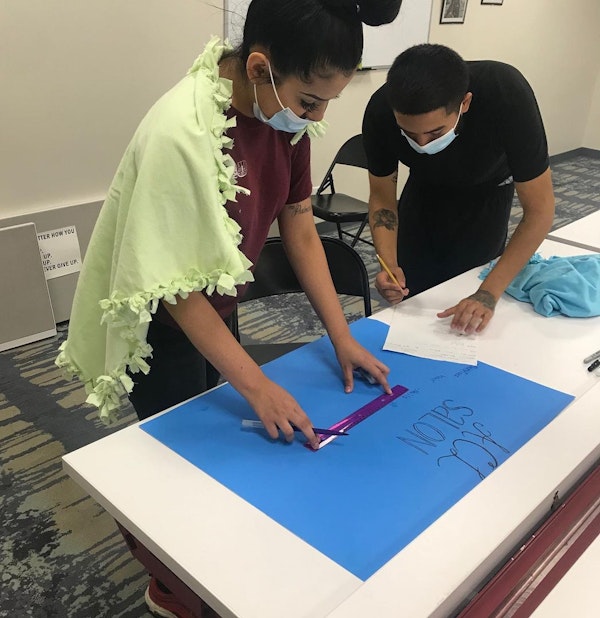

Café Momentum interns work on presentations for a "Shark Tank" lesson in 2020. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

Café Momentum interns work on presentations for a "Shark Tank" lesson in 2020. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

The American dream for a lot of people is a very specific idea. Why do we need to expand on that? Why are young people, with these kinds of barriers especially, so critical in how we think about the American dream in the future?

As cliché as it is to say, it’s the truth. Young people are the future of our country, period. They are the future leaders, they’re the future decision makers, and they need to be nurtured as such. They need to be respected as well.

I think that, without question, we live in arguably the greatest country in the world, in the history of the world. I think sometimes we struggle to live up to the ideals that we hold of ourselves. A glaring example of that is the inequity gaps in race. Things like a white high school dropout makes more income than a Black college graduate — that’s a fact. It’s one thing to acknowledge it, it’s another thing to dig into the root of what has allowed that to happen. I think that we have done historically, unfortunately, a really great job at hiding these things.

A glaring example of that is the inequity gaps in race…. It’s one thing to acknowledge it, it’s another thing to dig into the root of what has allowed that to happen. I think that we have done… a really great job at hiding these things.

Now, I hear a lot of people talk about the juvenile justice system being broken, and they couldn’t be more wrong, it’s not broken. Systems aren’t broken; systems are producing the outcomes that they’re built and designed to produce. When you don’t like a system, it’s not that the system is broken. It’s that the system is the incorrect system that you need to use, and you need to rebuild a new system.

That’s core to us at Café Momentum, as we look to expand and grow across the country. Because we can build programs all around the country, and we intend to do that, but a program that works with 130 to 200 youth a year, when you have almost three-quarters of a million youth entering the juvenile system every year, is barely chiseling the top of that iceberg. But hopefully we’re growing, and expanding, and beginning to build conversation, and advocacy, and support around these young people.

That we’re beginning to show that our restaurant and program aren’t so much a restaurant program but actually a new model for the way the juvenile justice system should operate, a model that says, “When a young person comes from trauma, and hunger, and housing insecurity, they shouldn’t be put in handcuffs and isolated and told they’re bad. They should be wrapped into an ecosystem of support. And provided tools, resources, love, an opportunity to truly achieve their full potential in life.”

You’ve obviously been affected by the impacts of COVID-19, but you met the challenge in such an innovative way, not only to support your interns, but to also be a resource more broadly within the community. How did that come to play?

For us, going into the pandemic, we saw the writing on the wall pretty quickly. The last night that we kept the restaurant open, we had seven people show up for dinner.

From just a pure safety standpoint, I knew we should probably shut down our restaurant, but I wondered if that was really an option for us, because we are a source of income and financial livelihood for the young people that we serve. There could be significant, horrendous impact if all of a sudden their income was completely taken away.

At the same time, I got an email from one of our supporters who explained the situation in the Richardson Independent School District. Their students would likely not be returning after spring break and the schools would be shutting down. Unfortunately, there’s a large number, over half of the student body, who looks to school as their primary source of food nutrition. While there are programs set up to make sure that there’s food supplemented at home during spring break, there is not a program set up for the week after spring break, and the week after, and the week after.

So, I had an idea to convert the restaurant into a food distribution hub and make food and meals for food insecure students and their families. I chatted with the team that evening, met with the staff the following day. Within 72 hours, we had converted our restaurant into a food distribution hub. Over the course of the first 14 weeks of the pandemic, we produced over 350,000 meals for food insecure students in Richardson and Dallas ISDs and several other organizations across Dallas.

An intern at work at the Café Momentum food hub in June 2020. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

An intern at work at the Café Momentum food hub in June 2020. (via Instagram @cafemomentum)

For us it was wonderful, because it allowed us to continue to provide income for the young people that we serve. It allowed us to continue to provide a safe space and quality time with the young people that we serve. And it allowed us, as an organization, to show the community that these young men and women who had previously been deemed “throwaway” were actually the young men and women that were stepping up to help the community when it needed it the most. It was a really powerful statement for them.

It allowed us… to show the community that these young men and women who had previously been deemed “throwaway” were actually the young men and women that were stepping up to help the community when it needed it the most.

It was pretty amazing even to hear some of the interns commenting that, “This used to be me and my mom. We used to go to the line at this place and we would wait for a box of food. Now I’m on the other side of that and I’m serving people.” They would talk about how full circle it was, and how good and empowering it felt.

Can you talk a little bit about how you responded to the killing of George Floyd last summer, and why that was such an important moment for the young people that you serve?

The thing that I kept going back to is, “This is the time you listen.” It’s not a time for me to talk, it’s time for me to listen, it’s time for me to reflect, and it’s time for me to unpack. So, I did, I listened. I heard our kids saying, “Well, does it matter anymore? Does it matter that George Floyd was murdered, because the first protests that went wrong, it erases everything. Now nobody cares. We’re never going to be treated equal in this country, because everybody will always just focus on that.”

It’s heartbreaking. Media was reaching out and wanting to know about our windows being broken [during protests in downtown Dallas]. I thought that I shouldn’t be the person that’s talking about it, because if I’m the person that’s talking about this, it is absolutely counter to what we stand for as an organization. So, we started putting large sticky notes all over the walls of the restaurant. On some of them we wrote, “I want…” On others we wrote, “I feel…”

Any time an intern felt like writing something, they could just stop what they were doing, walk over, and write something. Then, we took the plywood that covered the broken window in the front of our restaurant, and we took a bunch of the things that they said and began to write them on the plywood. That was our statement as an organization. We stood as the voice of the young men and women that we serve.

How can people directly engage in support of so many of the changes that you’ve outlined across this conversation?

Have a seat at our table and see firsthand the inequities. Understand what happens when we begin to build equity into our own community and what that change looks like. For us growing and expanding, our goal is to have 50 Café Momentum programs operating in different communities across the country, in the next 10 years. But more importantly, our goal is to bring this issue to the table of 50 different communities, and for those communities to see that they are actually the change.

In 2021, we all need to keep listening. I think everything has become so divisive, and everything has become polarizing. And the problem is because no one’s listening anymore, we just turn a blind eye. I think that that’s really the power of Café Momentum, and that’s the power of breaking bread together. It makes you just stop and listen. I think that if we did more listening, then we would all collectively get back into creating the solutions and building the systems that build a more just and equitable society.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.