Don't Blame Trade for Killing the Middle-Tier Jobs We Need

The polarization of the U.S. labor market has resulted in availability of high-skill jobs as well as availability of low-skill jobs. The lack of jobs in between those two ends of the spectrum presents a problem for our country.

The hourglass economy: We've seen job growth at the top and bottom of the job market, but not in the middle.

The hourglass economy: We've seen job growth at the top and bottom of the job market, but not in the middle.

If you want to understand why the middle class is under such pressure, look no further than the decline in jobs for middle-skilled workers. At the very time that a growing share of U.S. workers have landed high-skilled or low-skilled jobs, opportunities for workers in mid-wage, mid-education positions have hollowed out. As a result, the nation is witnessing a shrinking share of so-called middling jobs.

At the very time that a growing share of U.S. workers have landed high-skilled or low-skilled jobs, opportunities for workers in mid-wage, mid-education positions have hollowed out.

The polarization of the U.S. labor market poses important questions for policymakers at the federal, state, and even local levels. For starters, they need to learn from communities and regions that actually are producing middle-class jobs. They also need a better understanding of how to prepare workers for such employment. As those lessons are learned, the job prospects for middle-skilled workers can look as bright as those for high-skilled and low-skilled workers.

The hourglass economy

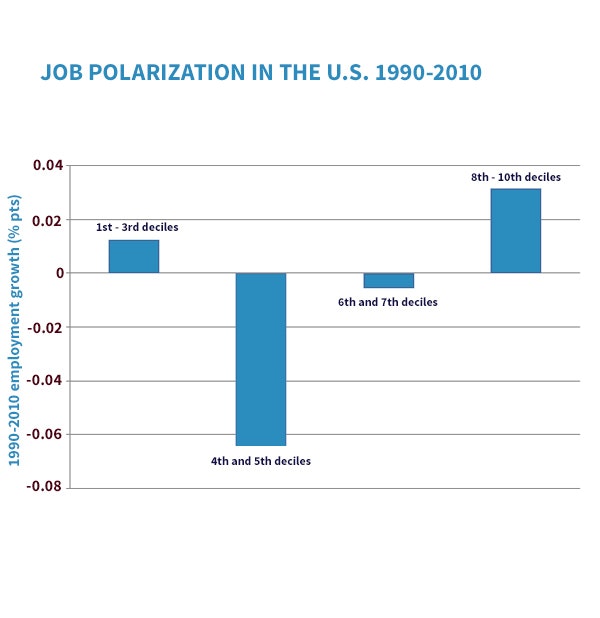

Some economists call the current disparity in job creation an “hourglass economy.” The situation looks good at the top or bottom, but not in the middle. You can see the shape of this economy for yourself in the chart below, which draws upon U.S. Census data from 1990 to 2010. The disparities between the different groups dramatically illustrate the disappearance of jobs that require mid-level education.

From 1990 to 2010, the U.S. saw growth in the top and bottom groups of jobs. The top group consists of jobs requiring high education and paying high wages and includes financial services, education, and engineering occupations. The bottom group consists of jobs requiring only low education and paying low wages and includes occupations like in home health aide, bank tellers, and farm workers. Encouragingly, employment for those top and bottom categories of workers increased over the 20-year period.

But, unfortunately, positions for Americans in the second group starkly declined. These jobs require low-to-middle-levels of education and are paid low-to-middle-level wages. Typical occupations include salespeople, truck drivers, and machine operators.

The drop-off looks even worse when you tack on the slight dip in employment for the third group. These jobs require medium levels of education and are paid commensurate mid-level wages. Typical occupations include secretaries, Realtors, and supervisors of sales, production, or construction workers.

Figure 1

Figure 1

A raging debate is going on among economists, policymakers, and workers about what is causing this disparity. One theory is that the openness of our borders has allowed goods and services to move easily across them, disproportionately impacting industries with low-to-middle-skilled workers. Advocates for that conclusion point to China’s emergence as an economic superpower and an export powerhouse. Another theory argues that the main driver of job polarization is the role of technological change, including automation and computerization.

A raging debate is going on among economists, policymakers, and workers about what is causing this disparity.

Technology is driving change

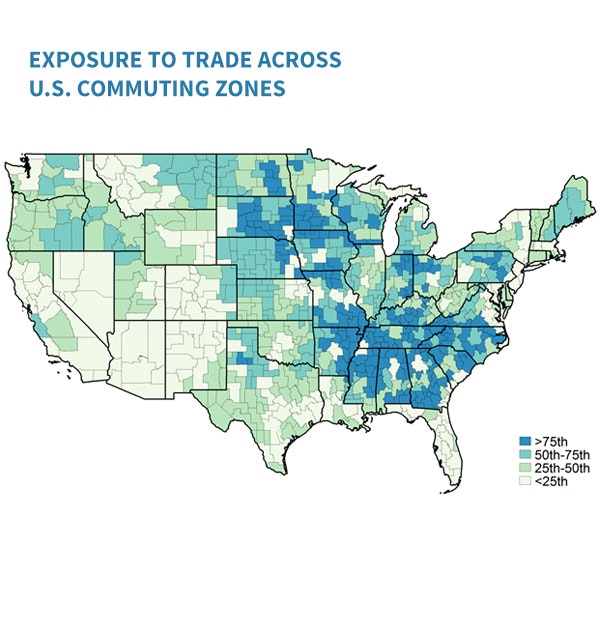

Data that Daniel Millimet, a fellow SMU economist, and I recently collected shows that technological change is driving the disparity. In our study, we divided the U.S. into 741 “commuting zones” and measured how vulnerable each zone is in its exposure to trade or technological change.

The places that were at risk of trade impacting them are ones with many workers employed in occupations vulnerable to import surges from China between 1990 and 2010. Cabinet makers and textile machine operators were among the occupations that fit this category since the furniture and textile industries faced particularly strong competition from China during that period.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows that, for the most part, these places are in median-sized locations across southern states. They include the Carolinas, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

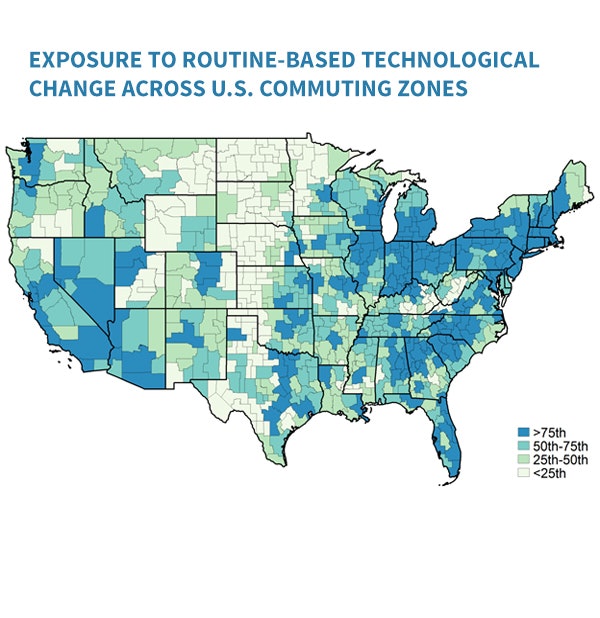

And a place was vulnerable to technological change when many of its workers were employed in occupations endangered by automation and computerization of routine tasks. Those occupations include secretaries and typists, bookkeeping clerks, butchers, and pharmacists.

Figure 3

Figure 3

And Figure 3 shows that we found this to be most true in and around big cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, Newark, Dallas, Cleveland, Charlotte, Oakland, and Milwaukee.

The deeper we looked into the commuting zones, the more we found that technology better explains today’s job polarization. It turns out the places with the highest vulnerability to automation and computerization were the places that experienced the greatest degree of job polarization. Meanwhile, places vulnerable to imports have little relative decline in middle-skilled jobs. Figure 3 illustrates how technological change creates job polarization across a wide cross-section of the country.

It turns out the places with the highest vulnerability to automation and computerization were the places that experienced the greatest degree of job polarization.

Policy implications

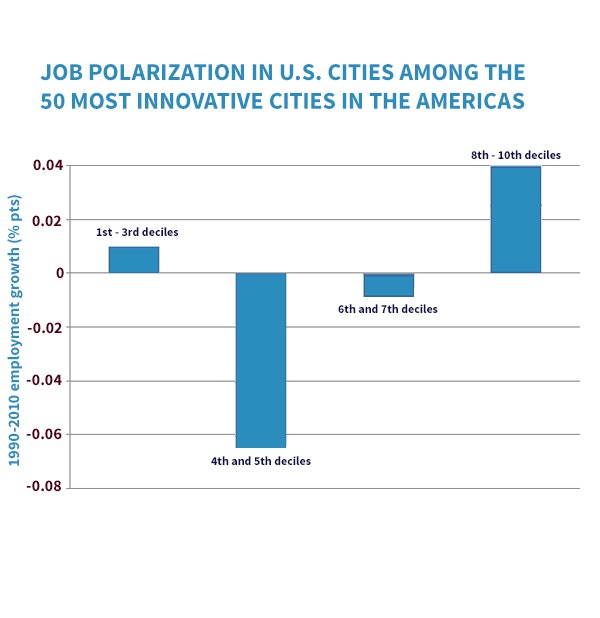

Some suggest that we should strive for more innovative cities like San Francisco, Austin, and Pittsburgh. But even they were not immune to the impact of technological change. In fact, so-called innovative cities struggle to grow a wide range of jobs. Among the 50 most innovative cities in the Americas according to 2thinknow, none managed to grow employment in three of the four job groups.

By contrast, and this could hold a clue for the future, smaller regions did better in producing sizable employment growth in all but the second group.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Places like Altoona, Pennsylvania; Lincoln, Nebraska; and Victoria County, Texas, are among the commuting zones where jobs grew substantially in three of the four employment categories. A common theme among such places is that their workers tend to be employed in occupations that are not so vulnerable to technological change.

The surprising difference between innovative cities and smaller regional areas complicates policy prescriptions. The solution cannot merely be that workers could benefit from becoming more mobile, as is sometimes suggested.

Altoona, Pennsylvania, where employment has grown with jobs less vulnerable to technological changes.

Altoona, Pennsylvania, where employment has grown with jobs less vulnerable to technological changes.

The U.S. needs a better understanding of how smaller regions like Altoona, Lincoln, and Victoria County grew jobs across a wide range of workers with various education backgrounds and wage levels. We have a lot to learn about what is happening in these communities. Is it merely that these locations are not so vulnerable to technological change or are they doing things differently than larger cities?

At the same time, bigger metropolitan areas need a better grasp on the following issue: Is technology prompting their firms to cut back their demand for tasks that workers in traditional middle-tier jobs have held? Or, are their firms seeing a dearth of qualified applicants to fill such jobs?

After understanding the answers to these questions, state and local governments can play an active role in gearing educational systems and incentives towards the needs of these workers and local firms. Emphasizing vocational skills will undoubtedly be crucial.

… state and local governments can play an active role in gearing educational systems and incentives towards the needs of these workers and local firms.

Strategies like this will help communities grow middle-wage jobs for workers who possess the skills to occupy them. This will take time, but it will help expand America’s middle class.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article The Benefits of Homeownership Mean We Should Still Believe in the American Dream An Essay by J.H. Cullum Clark, Director of the Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative

-

Next Article Veterans: A Building Block of the Middle Class An Essay by Colonel Matthew Amidon, Director of the Military Service Initiative at the George W. Bush Institute