Is Being an American and a Globalist at Odds?

Can one be both a proud American and a globalist? Matthew Rooney and Max Boot discuss in a lively exchange why the two are not mutually exclusive.

The issue of identity is central to our debates over immigration, nationalism, and globalization. Some believe that globalization strengthens the country through more jobs, greater security, and a broader culture, while others fear that being part of a global economy that includes the movement of goods and people across borders weakens our sovereignty and increases the chances for terrorism.

In this email conversation between Matthew Rooney, the Bush Institute’s Economic Growth Initiative Director and a retired U.S. Foreign Service Officer, and Max Boot, the Jeane J. Kirkpatrick Senior Fellow for National Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations and a widely-published historian, Catalyst Editor William McKenzie asks what national identity means to them and how they square that view with their support for the global economy.

Is being an American and a globalist at odds? Or is this a false choice?

Boot: This is a false choice. There is no tension between being an “American” and a “globalist.” Just as there is no tension between being (in my case) an Upper West Sider, a Jewish American, a New Yorker, a conservative, a San Francisco 49ers and New York Knicks fan, an American, a “citizen of the world” (meaning, simply, a world traveler), etc. We all have multiple identities that co-exist.

Some loyalties, of course, are felt stronger than others — and there is no question that I feel greater loyalty to the United States than I do to either my state or to the world as a whole. But that doesn’t mean that I should have an antagonist relationship with the smaller or larger entities.

It’s not even clear what being a “globalist” means since it’s become an all-purpose term of derision. But if it’s someone who believes that America is stronger when we take a leadership role in world affairs, that free trade is in our benefit, that we should be open to immigrants, and that we should champion a free and liberal world order — then sign me up.

If we turn our backs on globalism and retreat into isolationism and protectionism, we will be back in the 1930s. That didn’t work out so well. By contrast the post-1945 era of globalism, underwritten by the United States, has made our country the richest and most powerful in history.

“The post-1945 era of globalism, underwritten by the United States, has made our country the richest and most powerful in history.”

— Max Boot

U.S. funds helped rebuild Europe after World War II, ushering in an era of globalism. A Marshall Plan sign hangs as workers use European Recovery Plan funds to help rebuild Berlin. (Bettmann Collection/Getty Images)

U.S. funds helped rebuild Europe after World War II, ushering in an era of globalism. A Marshall Plan sign hangs as workers use European Recovery Plan funds to help rebuild Berlin. (Bettmann Collection/Getty Images)

Rooney: I couldn’t agree more: This is a false dichotomy that we have fallen into.

If you look at the history of globalization broadly defined – as far back as Charlemagne at the end of the first millennium – the successful globalizers have generally been strong states with a strong sense of national identity. Highly globalized nation-states like Germany, France, and the United Kingdom have survived and thrived.

Our challenge is to rescue national identity from nationalism, to create an affirmative nation-ness that can be a focus of pride and affection without seeking conflict with other polities. Only such a nation and the people of such a nation can successfully trade and treat with other nations, precisely because they know who they are and what they stand for.

“Our challenge is to rescue national identity from nationalism, to create an affirmative nation-ness that can be a focus of pride and affection without seeking conflict with other polities.”

–Matthew Rooney

The United States is such a nation, and Americans are such a people. We can do this, and it is perplexing to me that we are struggling with it all of a sudden.

Boot: The reason we are struggling with the issue of “globalism” now, Matt, is because it has become an all-purpose boogeyman that is blamed for whatever ails our country and our economy. “Globalism,” in fact, has long been a convenient piñata for populists and ultra-nationalists — along with associated code words such as “international bankers.” There has always been a strong tinge of nativism, xenophobia, racism, and anti-Semitism behind the anti-globalist movement.

The anti-globalist movement gained strength in the 19th century when globalism was blamed for the dislocations of the Industrial Revolution. Today globalism is blamed for the dislocations of the Information Revolution.

The Donald Trumps and Steve Bannons seem to imagine that we can somehow stop companies from making products abroad, stop consumers from buying imported goods, and shut our doors to all immigrants, while kicking out some 11 million undocumented immigrants who are already here — and by so doing we will return to some imagined 1950s paradise where every family was straight out of Leave it to Beaver.

“The reason we are struggling with the issue of ‘globalism’ is because it has become an all-purpose boogeyman that is blamed for whatever ails our country and our economy.”

–Max Boot

Leave aside the question of whether this is even desirable; we have become sensitized, after all, to the racial and sexual inequalities that underlay earlier periods of our history. The larger issue is that there is simply no way to turn back the clock — and if we try to do so, by cutting ourselves off from the world, we will pay a heavy price in lost prosperity and security.

We don’t want to become a hermit kingdom like North Korea. We want to remain the open, dynamic, innovative country we have always been — and the only way to do that is to remain intensely engaged with the rest of the world.

Rooney: I have always found remarkable in this whole debate — and I have watched it unfold in numerous countries including the U.S. since the end of the Cold War — is that the anti-globalists never explain why there are no wealthy, powerful closed societies, while all the wealthy, powerful societies are open to trade, investment and ideas.

There is a cottage industry in outlining parallels between the global debate today and the situation immediately preceding the First World War, but I do think there are some useful lessons there.

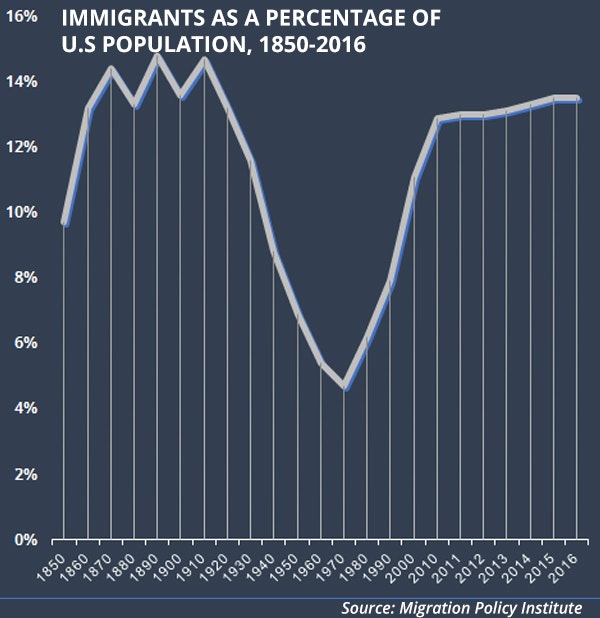

For one, we have only now reached the point where the proportion of foreign-born persons in the U.S. is comparable to that in 1914; I wonder if there is a rule of thumb as to how high it can go before there is a social and political backlash? That limit seems to be 14% for the United States, I’m afraid.

As to the impossibility of rolling it back, I hope you are right. My fear is that history — including 1914-1945 — is actually replete with examples of how “globalization” can be rolled back, and how disastrous the consequences are. The issue to my mind is how to avoid making people feel that they have to choose between identity and prosperity — history suggests that people choose identity every time.

“The issue to my mind is how to avoid making people feel that they have to choose between identity and prosperity – history suggests that people choose identity every time.”

–Matthew Rooney

Matt, you mentioned rescuing national identity from nationalism. And, Max, you have written a good bit about nationalism. So, what does national identity mean to each of you?

Rooney: I was raised in a family of mixed faiths — if you agree with me that Roman Catholicism and Christian Science are pretty disparate — in an exurban community in New England that brought working-class and highly educated people together successfully. By the time I encountered other nationalities as a young adult, it was clear to me that bonds like that did not and should not divide people or prevent them from communicating.

This is a bit of cultural legerdemain that the United States has pulled off that makes us as Americans uniquely able to navigate a globalized world: I feel a strong sense of American identity, but made it my life work as a Foreign Service Officer to communicate American views to others.

At every stage, it was clear to me that being forthright about my perspective — American, free-trader, pro-immigration, comfortable with ethnic and identity diversity — was what made it possible for me to communicate successfully across those cultural, linguistic, and national boundaries. It sounds paradoxical, but we are successful “globalists” because we are proud Americans and vice versa.

“It sounds paradoxical, but we are successful ‘globalists’ because we are proud Americans and vice versa.”

–Matthew Rooney

Boot: I am an American by choice, not by birth. Admittedly, it was my parents’ choice, not mine. I came here in 1976 at age seven from the Soviet Union along with my divorced mother and my grandmother. I remember being puzzled by innovations such as hamburgers and French fries, which had not yet made their way behind the Iron Curtain.

At first everything seemed strange and alien. But I was determined to adapt as quickly as possible. I learned English and in the process all but forgot Russian. Like countless immigrants before me, I proudly adopted an American identity. I never thought of myself as a ‘Russian American’ or a ‘Jewish American.’ To my mind, I was simply an American, period.

“I never thought of myself as a ‘Russian American’ or a ‘Jewish American.’ To my mind, I was simply an American, period.”

–Max Boot

Anyone meeting me, who does not know my life story, is usually surprised to hear that I wasn’t born here, and when I explain that I was born in Moscow, my interlocutors usually assume my parents were American diplomats.

That, to my mind, is the genius of America: We have done a better job of assimilating immigrants from all over the world than any other country. Immigrants have been a force of dynamism in our country since the beginning, and today they give us a critical advantage over more closed, and rapidly aging, societies such as Japan and South Korea, which are not as successful as we are at integrating newcomers.

My fear is that the Trump administration may be squandering our advantage by acting in such a hostile fashion toward immigrants. Trump is not only determined to stop the flow of illegal immigrants — he wants to cut legal immigration by 50 percent, too. More broadly, Trump has championed the interests of working-class whites over those of other ethnic and racial groups.

This is a very dangerous game. The President is causing those of us who aren’t white and native-born to think of ourselves increasingly as outsiders — as somehow less than “true” Americans. That is anathema to all that America has stood for, as a country that welcomes the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Being part of a global order means people may move more easily across borders. And that may come with new cultural mores and beliefs. Is this tension resolvable?

Rooney: All that is true, and Max is correct that the United States has consistently done better than other countries at assimilating immigrants. It is worth remembering that my people — the Irish — were shunned and abused when they arrived in great numbers because they were Catholic and the broader, largely Protestant society feared that their presence would … what? Force everyone to convert? It sounds silly in retrospect, but in the 1900s and 1910s people died fighting over it.

I’ve always thought, however, that the challenge presented by large-scale Latino immigration presents some unique challenges. For one thing, many Latinos came to this country from places you can drive to in a couple of days. As a result, they probably preserve a stronger tie to their country of origin than my forebears, who left Ireland because it offered them no future, of even Max’s, who left a country that slammed the door behind them.

The other salient fact is that there are millions of native-born, Spanish-speaking Americans who naturally create a different cultural and assimilation dynamic for Latin American immigrants today – the United States is the largest and richest Spanish-language media market in the world.

I think today’s immigrants will fully assimilate, but along the way American society will become a little more Latino than it ever became Italian or Irish a century ago. That’s not a bad thing – it makes us still more global, after all – but I will always remember visiting San Antonio in the early 1980s and being struck by signs in shop windows saying “We Speak English.”

“I think today’s immigrants will fully assimilate, but along the way American society will become a little more Latino than it ever became Italian or Irish a century ago. That’s not a bad thing.”

— Matthew Rooney

When I was assigned in Germany in the mid-1990s, I remember reading that salsa had replaced ketchup as the most-consumed condiment in the U.S. I resolved on the spot to take my kids to Latin America and expose them to Spanish, which is why we sought a transfer to El Salvador later that year.

Boot: Immigration has long sparked resistance in the United States. The first group of “outsiders” that immigrated to this country voluntarily were the Irish Catholics who flooded in after the Great Famine of 1845-1852. They were met with discrimination and hostility because they were not Protestants. So too were the Italian immigrants who came a bit later. Indeed “anti-papist” prejudice was so strong that only one Roman Catholic has ever been elected president. Similar tensions followed the influx of Eastern European Jews, who were looked down upon even by better-established German Jews. Anti-Asian prejudice was so strong that the Immigration Act of 1925 all but prohibited immigration by non-Europeans.

The barriers to immigration were lowered again in 1965, allowing a new wave of immigrants from countries such as China, South Korea, and India that have contributed greatly to America’s economic well-being in recent decades. At the same time, the poverty and unrest of Mexico and Central America led to large numbers of undocumented immigrants crossing our borders illegally in search of work.

The impact of these illegal immigrants is debatable, but from all that I have read they have been on balance a net plus for our economy, in many cases performing jobs that native-born Americans refuse to do.

However beneficial, this recent wave of immigration has sparked a backlash just as the immigration of the late 19th/early 20th centuries did. Just as universities once had quotas for Jews, so today many of our elite institutions of higher learning have de facto quotas for Asians, and it has become fashionable in certain circles to scapegoat immigrants for economic dislocations such as the hollowing out of the Rust Belt.

The tension between newcomers and native-born Americans remains very real — but we have done a better job of managing such tensions than any other country in the world, precisely because we have never identified Americans by blood and birth. An American is anyone who comes here, works hard, and embraces the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. That’s it.

“We have never identified Americans by blood and birth. An American is anyone who comes here, works hard, and embraces the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. That’s it.”

–Max Boot

Boot: I don’t share Matt’s concerns about Latino immigration. Yes, Latinos are adding a little spice to the white-bread American culture — I’m currently in Los Angeles where there is a taco truck on every other corner. I love it! Even though I don’t speak Spanish, I have nothing but admiration for the hustle and grit of these newcomers. This is the kind of cultural mixing pot that makes America such an interesting and dynamic place.

The Dulcieria de las Americas ("Candy Store of the Americas") shop in Dallas. (Andrew Kaufmann / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

The Dulcieria de las Americas ("Candy Store of the Americas") shop in Dallas. (Andrew Kaufmann / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

I’m not worried about Latinos failing to assimilate simply because their countries of origin aren’t located an ocean away. Remember, that in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there were plenty of urban ghettos and small towns in America where the dominant language wasn’t English — it was Polish, or Russian, or German, or Italian, or Swedish, or what have you. Yet the second and third generations rapidly assimilated and in most cases forgot their parents’ language. I see the same dynamic occurring today with Latinos.

After all, with English sweeping the world, it’s hard to believe that the one place where it will not be spoken will be in Latino communities in America. Our common American culture and our common English language are so strong, so seductive, that they will win over today’s newcomers just as they won over the newcomers of yesteryear.

Rooney: Have you been to Miami lately? I once had a nice conversation at a cocktail party in San Salvador with a Mexican businessman who had been transferred there from Miami by his company. We were talking about where our kids went to school in San Salvador, and he was gushing about how, thanks to the Escuela Americana, his kids would finally learn English after their several years in Miami!

I hasten to add that this is a natural thing: Florida, Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, California were all part of the Spanish Empire and Mexico for much longer than they have been part of the United States. Hispanic culture is very strong and cohesive, too — one of the reasons that Spain was one of the early leaders of European globalization — and will likely always coexist and persist alongside “mainstream” Anglo culture in the U.S.

When the Pilgrims stepped onto Plymouth Rock, Saint Augustine, Florida had been a functioning community for almost 80 years. We should acknowledge that this is an integral part of American culture and celebrate it.

What would you all say to those who worry that a modernization of our immigration system would lead to terrorism of the kind we recently saw in New York or drug cartels creating menace in Texas, California, and elsewhere?

Boot: The 9/11 terrorists weren’t immigrants; they entered America on tourist visas just like millions of others. Neither was Omar Mateen, the perpetrator of the Orlando massacre in 2016 — the second-deadliest act of terrorism on American soil since 9/11. He was born in Hyde Park, N.Y., to a family of Afghan immigrants. Sayfullo Saipov, who killed eight people with a truck in New York on Halloween, was an immigrant (he came from Uzbekistan), but he was radicalized after arriving here.

We should definitely do “extreme vetting” of those coming to America, whether for tourism or work or immigration, but it would be a grave mistake to slam our doors shut to foreigners in the name of fighting terrorism. We cannot simply stop everyone from coming here. We cannot even stop every Muslim, as Trump once suggested. That would be immoral, illegal, and unwise. The greatest terrorist threat we face is from the inside, not the outside — it is the danger of Muslims such as Saipov who are already here being won over to Islamist extremism.

“The greatest terrorist threat we face is from the inside, not the outside — it is the danger of Muslims such as Saipov who are already here being won over to Islamist extremism.”

–Max Boot

There is no surefire way to prevent this from happening, but successfully assimilating Muslim immigrants is perhaps our most important line of defense. We do a much better job of this than do European countries such as Germany, France, Belgium and Britain, all of which have large, unassimilated communities of Muslims that are a breeding ground of extremism.

Flowers mark the location where terrorist Sayfullo Saipov crashed a truck into cyclists along a Manhattan bike path ending a rampage with a truck on November 7, 2017 in New York City. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Flowers mark the location where terrorist Sayfullo Saipov crashed a truck into cyclists along a Manhattan bike path ending a rampage with a truck on November 7, 2017 in New York City. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

The U.S. must make clear that we are not anti-Islam in order to win the cooperation that our law enforcement and intelligence agencies need from Muslims both at home and abroad to expose and catch the extremists in their midst. The kind of ugly anti-Muslim rhetoric that Donald Trump has engaged in, along with his attempts to bar as many Muslims as possible from coming here, actually makes us less safe by alienating the Muslim community and increasing the risk of radicalization.

Rooney: I have a hard time seeing a link between immigration and terrorism, I confess, particularly if we define “immigration” to refer to people who have come to this country to live permanently and become permanent residents and eventually citizens. The few such people who have carried out acts of terrorism can be counted on your fingers, while those who have made important innovations and provided employment for millions of Americans are far more numerous, not to mention those who have come here and led peaceful lives. Certainly, we and our European friends face a challenge in understanding and countering radicalization – but we accept far greater risks when we give 16-year-olds the keys to the car.

As to the cartel threat in the U.S., one of the striking things about U.S.-Mexico relations is how small that threat is. Even when Juarez was one of the most dangerous cities in the world, El Paso was and remains among the safest, and this is true across the border.

The best thing we could do to counter any real threat here would be to normalize the status of the Mexicans living here without documentation, which would open legitimate opportunities to them and give them the confidence to cooperate with law enforcement; modernizing our immigration system would probably reduce, not increase, the threat posed by the Mexican cartels in the U.S.

“…modernizing our immigration system would probably reduce, not increase, the threat posed by the Mexican cartels in the U.S.”

–Matthew Rooney

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article We Are America A Conversation with Ruben Navarrette, Syndicated Columnist and Bush Institute Education Reform Fellow, and Reverend Samuel Rodriguez, National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference President

-

Next Article DACA Is Dead, DACA Lives Again An Essay by Juan Carlos Cerda, Texas Dreamer