How Mississippi Reformed Reading Instruction

By passing education reform legislation, Mississippi took an important first step toward prioritizing reading achievement. But full support – adequate infrastructure, capacity, and funding – is critical to ensuring success.

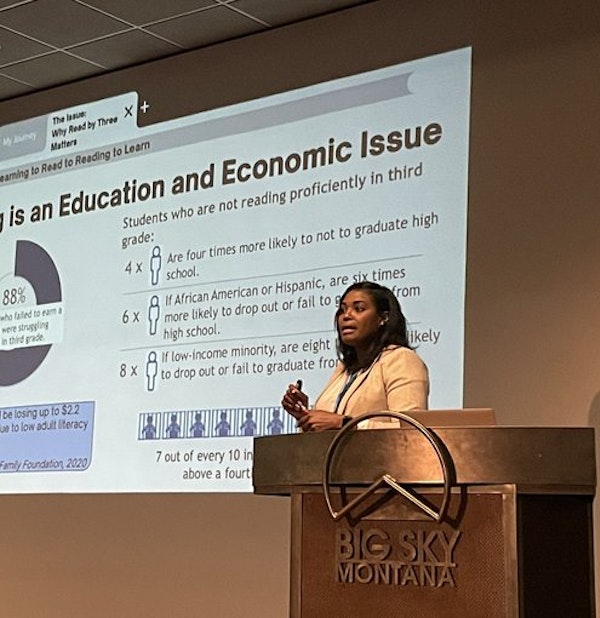

Kymyona Burk at the Delaware Reading Summit (Kymyona Burk/Twitter)

Kymyona Burk at the Delaware Reading Summit (Kymyona Burk/Twitter)

After years of struggling with student reading deficits, Mississippi legislators made history in 2013 by passing the Literacy-Based Promotion Act. For the first time, Mississippi had a state-led, comprehensive approach to improving literacy outcomes for all students.

After Governor Phil Bryant signed the bill, the Mississippi Department of Education embraced the measure, and everyone advocating for the law began to work with state education leaders and teachers to effectively implement the act. They also started to communicate its expectations to families.

Adopting a law is a great first step. It gets everyone on the same page around expectations. It shows the state has put a stake in the ground to prioritize reading achievement and literacy improvement.

However, effective implementation is key to ensuring the law is successful. The role of the state agency is also critical. There must be sufficient infrastructure, capacity, and funding to lead implementation and provide guidance and adequate technical support.

Our first step in translating the law into practice was training teachers in the science of reading.

Applying the law to the classroom

Our first step in translating the law into practice was training teachers in the science of reading. That science comprises a body of research that incorporates insights and research from multiple disciplines, such as developmental psychology, educational psychology, and cognitive neuroscience. A coalition of experts led by the Reading League reports that the science of reading informs “how proficient reading and writing develop; why some have difficulty; and how we can most effectively assess and teach and, therefore, improve student outcomes through prevention of and intervention for reading difficulties.”

We needed a common language to transition to instruction aligned with the science. For that reason, we adopted the Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling, known as LETRS.

We knew that some teachers were taught whole language or balanced literacy techniques, both of which differ from what research demonstrates works best in teaching reading. With a new emphasis on the science of reading, we wanted to start by developing this common language and improving teacher knowledge in this science.

Next, we put literacy coaches in the state’s lowest-performing schools. This move ensured that teachers not only had the theory behind how to teach reading but also had support while instructional practices were being shifted to those grounded in the science of reading.

It is my belief that a literacy law is an equity law, so states must make a bold stand and say they want this science-based approach.

The coaches modeled how to teach lessons, plan with colleagues, and analyze data to make instructional decisions. They also supported educators with feedback on their instructional practices and delivery.

Kymyona Burk addresses a Montana conference.

Kymyona Burk addresses a Montana conference.

Results tell the story

Six years later, our scores on the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) underscored the return on investment. NAEP scores showed that Mississippi was the only state with statistically significant improvement in fourth grade reading on that year’s assessment.

Over the course of six years, our fourth graders showed a gain of 10 points on the NAEP reading exam, or approximately a year’s worth of advancement in reading. Yes, the pandemic had its effect and our fourth grade reading scores on the 2022 NAEP exam dropped by two points. But we remained ahead of the national average on fourth grade reading scores. And, according to the 2022 NAEP report, those scores showed no significant change while 30 other states showed significant change.

Since Mississippi passed its law a decade ago, several states have passed similar measures. This year alone, in my position with ExcelinEd, we supported nine states that adopted policies around early literacy. We also helped protect laws in six states that were looking to make changes to protect or strengthen their early literacy policy.

When I testify before committees in states, engage with stakeholder groups, or even talk to policymakers, I often begin with their data. It’s one thing for us to believe that we’re doing the right thing. But our data tells the true story.

Six years later, our scores on the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) underscored the return on investment. NAEP scores showed that Mississippi was the only state with statistically significant improvement in fourth grade reading on that year’s assessment.

We have to look at the data to ensure that all kids are on the path to reading proficiency. That doesn’t mean just our white kids, but our Black and brown students, our students with disabilities and our English learners. We can’t look generally across a population to declare success.

For example, we should look at whether we are continuing to see a reading gap between our white students and Black students. And what about between our white students and other subgroups? We want to make sure that we are doing what’s best for all kids.

In many states, policymakers as well as organizations with an interest in education are not aware of what their NAEP data says about their students’ performance. They know how students have been doing on their state assessments. But they need to look deeply into the data to begin having conversations about performance and opportunity gaps. We need to get people listening to what’s best for all kids.

Next steps

One obstacle to implementing this kind of law around the country is that districts often have a curriculum that is not aligned, or is in direct conflict, with the science of reading. Their curriculum may include Lucy Calkins’ Units of Study or Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell’s method of reading instruction.

Both of those methods, which cognitive scientists have rebutted, rely on strategies like using context or visual cues to guess the meaning of a word, otherwise known as the three-cueing strategy. There is now the need to focus on the instructional materials that states are encouraging school districts to adopt or mandating they do so. This year, Louisiana successfully passed a law to ban curriculum that includes three -cueing. They are the second state to take this action after Arkansas.

Since Mississippi passed its law a decade ago, several states have passed similar measures. This year alone, in my position with ExcelinEd, we supported nine states that adopted policies around early literacy.

Kymyona Burk and Tim Abram II raise awareness and offer policy ideas to improve the state of Black education. (ExcelinEd/Twitter)

Kymyona Burk and Tim Abram II raise awareness and offer policy ideas to improve the state of Black education. (ExcelinEd/Twitter)

Another obstacle is a misunderstanding of the retention component that may be included in some Read by Three literacy laws. If a student does not meet a specific score on a state assessment, then that student may be retained if he or she does not meet one of the good cause exemptions. Those exemptions may include opportunities for a retest and may also depend upon such nuances as whether the student is an English language learner.

One obstacle to implementing this kind of law around the country is that districts often have a curriculum that is not aligned, or is in direct conflict, with the science of reading.

We had to make it clear to parents and teachers that retention is not just a third-grade teacher’s responsibility. The goal is to screen students as early as kindergarten for reading deficiencies and begin interventions early. At the same time, we will keep monitoring a student’s progress and communicating with their parents and families. We don’t just want to say that we want children reading by the end of third grade. As a state agency, we had to be committed to helping them get there.

In Mississippi, the Legislature continues to annually appropriate money to reimburse school districts for screeners, fund professional development in the science of reading and instructional best practices, and fund literacy coaches among other supports. It took convincing to show parents and other stakeholders that this approach is best for their children and that we’re going to be your partner in this.

We had meetings across the state where we went to communities to talk to parents about what the law meant for their children. We also had sessions with teachers and leaders to talk about their roles and responsibilities. Communication ensured that all stakeholders knew their role in improving student outcomes.

Finally, colleges of education need to see themselves as part of K-12 student outcomes. Their reach does not end when their candidates walk across the stage and receive their degrees. Their reach impacts everything that a candidate does when they become a teacher and walk into their classrooms for the first time. Colleges of education play a huge role in ensuring that prospective teachers are ready on day one to teach children how to read.

Don’t get me wrong: Professional development should be continuous. But let us think about a day where we have our candidates exiting programs already possessing this core knowledge of how to teach kids to read that is grounded in the science of reading. The money that we spend on the initial professional development to build teachers’ knowledge can then be used for continuous professional development or allocated for literacy coaching.

It is my belief that a literacy law is an equity law, so states must make a bold stand and say they want this science-based approach. State education agencies should walk in their authority and ensure that their teachers are equipped, knowledgeable, and empowered to teach children how to read from the first day of class. That way, all states can start to see improvements in reading, the kind which will enable their students to enjoy the lifelong benefits of a quality education.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.