How a TV Show Changed Music and Africa

Bob Geldof stands at the forefront of musicians who have made an impact through both record sales and activism. His passion for Africa led to the monumental Band Aid and Live Aid projects, uniting the biggest names in music behind a common cause. More than 30 years later, Geldof still sees Africa as more than a charity case: It’s a continent filled with untapped potential.

Bob Geldof on stage at Live Aid, July 13, 1985. (Photo by Phil Dent/Redferns)

Bob Geldof on stage at Live Aid, July 13, 1985. (Photo by Phil Dent/Redferns)

Perhaps the most accurate description of Sir Bob Geldof is that he is a very smart person who happens to be a rock star. A founding member of the Boomtown Rats, in 1984 Geldof brought together a supergroup of artists known as Band Aid to raise money for famine relief in Ethiopia. Geldof has remained committed to understanding Africa ever since. The self-described Irish pub singer has studied Africa’s challenges, advocated for solutions, and literally invested in them. In this interview with The Catalyst’s William McKenzie, Sabrina Shaikh, and Andrew Kaufmann, Geldof’s wit, musician’s penchant for words, and passion for Africa are more than evident. So, too, is his honesty about his relationship with African advocates from Bono to James Baldwin to George W. Bush.

How did you get interested in Africa? Where did your passion for Africa come from?

Initially, from the television in 1984. The BBC ran a report on Africa one day at the top of their main six o’clock news. Prior to that, I had an interest in what was happening in South Africa with apartheid. I sort of became involved with that, mainly because I was the right age for the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan. Dylan was reading James Baldwin, so I started reading Baldwin, who was talking about South Africa.

When I was 15, a friend and I organized a march to stop the South African rugby team from playing the Irish team. Of course, I think the real reason was because I knew the South Africans were going to beat us, so we had to stop that at all costs. [Laughter]

The march was successful, so that was the beginning of looking at Africa from a different perspective. I was educated in Ireland, where the priests were always telling us about the missions over there. They went to “convert the pagans” but instead returned hyper-spiritualized by a people with their own profound theologies. Politically and spiritually, it all seemed exotic. This sort of thing stuck with me.

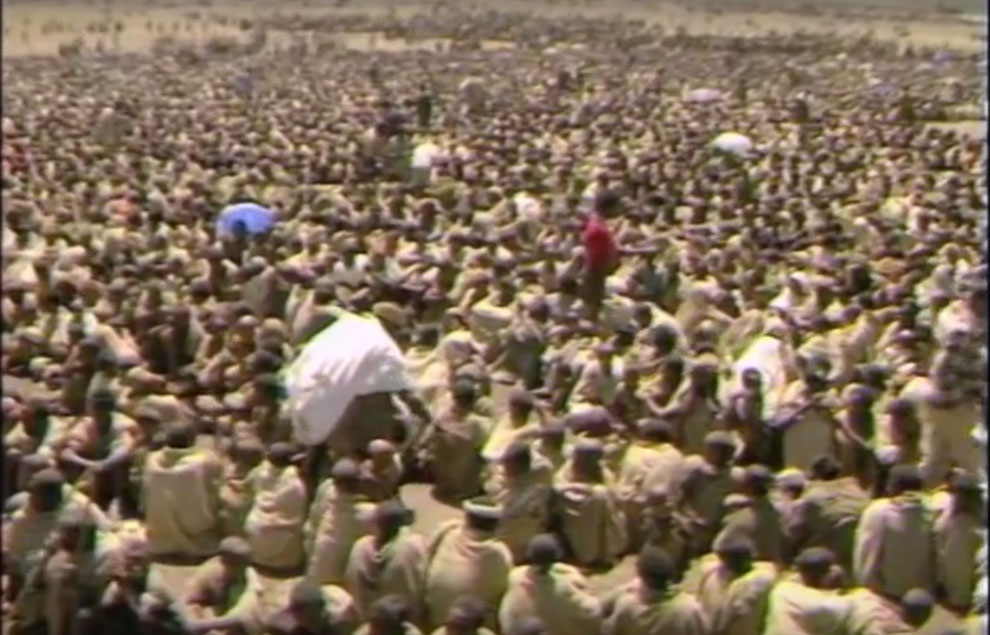

Then I got into rock ‘n roll, and am at home one night in late October and turned on the six o’clock news. The BBC gave 10 minutes to a report about what Michael Buerk, one of their leading journalists, stumbled upon when he was covering the civil war in Ethiopia, the longest-running war of the 20th century.

There was a town in northern Ethiopia, where literally hundreds of thousands of people just sat down to die. He spoke of 30 million people affected by famine. The report was absolutely devastating. It still resonates with me, and I sat there, very disturbed, and my wife had tears in her eyes. We just had had a little girl, and I was outraged by what I saw.

I thought it’s not enough to put a pound in the charity box. This requires something of the self. All I could do was write tunes, but I thought maybe we could make a record and get it out by Christmas. I thought we could make a hundred thousand pounds, give it to Oxfam or something, and be done.

There was a town in northern Ethiopia, where literally hundreds of thousands of people just sat down to die. The report was absolutely devastating… I thought it’s not enough to put a pound in the charity box. This requires something of the self.

I didn’t have the confidence that I could write and perform it myself, with my band, The Boomtown Rats. So I rang a friend in another band and said let’s do this together. We gathered all the main stars of the day and recorded Do They Know It’s Christmas? That was Band Aid, which became a massive phenomenon. Then Harry Belafonte called me one night, and Michael Jackson was on the phone, and they said they wanted to do it in America. USA for Africa happened, and I thought then it would be natural to join the two together in one concert, using then-relatively primitive satellite technology that we linked to the rest of the world. That in turn became a phenomenon, and raised around $200 million in 1985.

(L-R) George Michael, Bob Geldof, Bono, Paul McCartney, Freddie Mercury, David Bowie, and other musicians on stage at Live Aid on July 13, 1985. (Dave Hogan/Getty Images)

(L-R) George Michael, Bob Geldof, Bono, Paul McCartney, Freddie Mercury, David Bowie, and other musicians on stage at Live Aid on July 13, 1985. (Dave Hogan/Getty Images)

I quickly realized that politics is numbers. You can have as much money as you like, but if you really want to stop famine and other outrages of poverty from happening time and time again, the economics have to change. The way to change economics is through politics. The agents of change in our world, whether one likes it or not, are politicians. The way to get the politicians is numbers, and I think it was 1.2 billion people back in ’85 who watched Live Aid.

Those were serious numbers, so I was able to go to Downing Street and talk to Margaret Thatcher and go to the White House, where I talked to George H.W. Bush. I met [Ronald] Reagan briefly. Then I went to talk to [Francois] Mitterand, who was President of France, and subsequently the Pope and the Kremlin.

That’s when it began and culminated 20 years later at the Gleneagles G-8 meeting. The generation that had seen Live Aid was now in power. Our presence at the G-8 was to enable [then-British Prime Minister Tony] Blair to push through the cancellation of debt of the poorest countries and the doubling of aid to Africa.

From that point on, there was a slow development of economies in the more stable states, and the rise of democracy. It wasn’t simply because of us but because of a whole series of events. That’s it in a nutshell, and today I am still chairman of the Band Aid Trust, which we started in the wake of the record. That’s the continuing humanitarian effort.

I work on policy issues through the Africa Progress Panel with [former U.N. General Secretary] Kofi Annan, [former U.S. Treasury Secretary] Bob Rubin, and [former IMF President] Michelle Camdessus among others. We report to the G-7 and others.

I was a founding member of the ONE campaign with Bono. We do policy with eight million members, three million of which are in Africa.

Myself and my partners started 8Miles, a private equity fund, five years ago. We raised in excess of $200 million and employ about 10,000 people in Africa. We will start raising money for a second fund sometime around November.

The generation that had seen Live Aid was now in power.

We will go back to strategies in a minute. But looking at the big picture, what do you think is driving the emergence of an African middle class? And what can the West do to help grow it?

What’s driving it, of course, is development, economic growth. The amount it takes to be middle class in Africa is small compared to what it takes us to be there, but it is the way forward.

In about 2030, you’re going to have this vast amount of money being spent in the consumer sector. New wealth is beginning to evolve, but it’s constant with the growth of cities. You see this massive urbanization going on, and it’s essentially chaotic. But we saw that too in the development of our cities.

In about 2030, you’re going to have this vast amount of money being spent in the consumer sector. New wealth is beginning to evolve, but it’s constant with the growth of cities. You see this massive urbanization going on, and it’s essentially chaotic. But we saw that too in the development of our cities.

Another phenomenon is that through technology people become aware of another world. You get this massive drive to leave Africa and get to Europe. It’s tragic, but it is understanable. I left Ireland when I had no opportunity in the 1970s. If I had to cross the Mediterranean or the Sahara, I’d do it. They will keep coming to us in search of a better life. It’s normal. And Europe is only eight miles from Africa. That is the difference between the wealthiest and poorest continents.

To me, the way forward is to power up the continent, which is vast. Places are still in the primary phase of political development.

China has been a massive influence in Africa. They see it, as everybody else does, as the mother lode of all materials, which they need if their economy is to continue at its current pace. But that’s to make it too prosaic. In fact, resources only make up 25% of the continental economy.

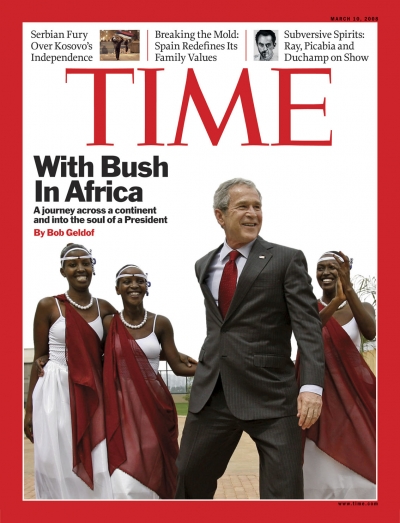

When I rode with President [George W.] Bush in the plane on a trip to Africa in 2008, he asked me if I thought China’s involvement was dangerous. I said no. Has it been benign? No, because they haven’t behaved well in lots of places. But they’ve learned quickly. They’re investing so much in the roads, rails, airports, stadiums, but there are grave dangers in some of their economic policies toward the continent, such as their conditional loans. They have just sent their first Chinese Djibouti. They are serious about this huge power that is rapidly emerging. They’re major players and cannot be ignored. It would be a catastrophic mistake for the U.S. to ignore the geo-strategic implications of all this activity.

Bob Geldof with President George W. Bush on Air Force One on Feb. 19, 2008. (Eric Draper / White House)

Bob Geldof with President George W. Bush on Air Force One on Feb. 19, 2008. (Eric Draper / White House)

Now, obviously there are elements like Al Qaeda and ISIS that can make hay because of poverty. Certainly, some of the activity will be ideological. But if you look at Boko Haram, people say they’re getting paid a thousand bucks a month. It’s a seriously-paying job, so the fighters say, “Where do you want us to go and shoot up next?” A lot of them are non-ideological. Poverty is the great base mover of violence.

But Africa, for some reason, usually doesn’t respond as violently as we’ve seen in the Middle East or as we’ve seen in places like Asia. There’s a greater tolerance. Some people see that Africans are simply fatalistic, and I don’t see it like that at all.

I find a great exuberance there. The potential for Africa is absolutely enormous. You’re seeing all the bumps of the past, but you’re seeing us in the present. To ignore Africa is to ignore 2050.

They’ve already made the technological leap. Kenya is so way ahead in technology. They will come up with some whiz-bang app. And they invented virtual currency. We’re all talking now about the end of cash. They did it years ago. They never had cash. They don’t trust their government. They don’t trust their banks, so they invented an app that was not Bitcoin but a virtual currency where bills are transferred.

Africa is changing rapidly, and it’s going to be a major force in the world economy.

The potential for Africa is absolutely enormous. You’re seeing all the bumps of the past, but you’re seeing us in the present. To ignore Africa is to ignore 2050.

How do you see technology reshaping something like farming in Africa? Seventy percent of Africa’s population works in that.

Hugely, because again, with mobile telephones, the farmer can find out what the market prices are and where the surplus is in the crop and can buy different seeds for buying next year. He can communicate with other farmers in valleys miles away or up in the highlands. He can ask what they are growing this year, and alter his crops if there is going to be a surplus.

The essential growth for fishermen and for farmers is to find out what’s happening in the local market, what’s selling, what’s not, what are the prices. Technology formalizes the prices, and in Addis Ababa there was a commodity exchange set up for the coffee farmers. It took a while for the Prime Minister to agree to do it. He was an old-school neo-Marxist, but he was a seriously smart guy.

Within six months, people were queuing up to join the market. I got to ring the bell a couple of times. If you’re selling, you put on a green jacket. If you’re buying, you put on a brown jacket. Around them were 27 screens showing the various markets in the country and they are linked to Chicago [Mercantile Exchange].

With mobile telephones, the farmer can find out what the market prices are and where the surplus is in the crop and can buy different seeds for buying next year. He can communicate with other farmers in valleys miles away or up in the highlands.

It is incredible to watch these once essentially feudal farmers trading on any commodity exchange, shouting and roaring. They get 10 minutes to do their trade, and you see the prices around the world changing because of these hitherto peasant farmers in the room in Addis Ababa. It’s extraordinary, and it’s wonderful. Technology is the big game changer. Africa is leaping before our eyes from feudalism to the technological age without stopping at industrialization.

So is the coherence of states, which comes about with the growth of the economy. The police can be paid. The judiciary can be paid. The army can be paid. They don’t have to shake you down at every roadblock.

These advances and the way they’re pertinent to people’s lives is definitely shaping and reshaping the continent. Politically, leaders can’t get way with the crap they were getting away with before. They just can’t. They’re called out on these things.

Look at Sudan and South Africa. The word spreads. It doesn’t have to be filtered through the Tammany Hall-style tribe chieftains. So, it’s interesting, what’s happening.

As we talk about the potential of Africa, it’s also home to the world’s 10 largest young populations, which suggests a growing workforce. How can Africa best capitalize on this?

It is by far the largest, youngest working-age population on the planet. But are there the jobs to fulfill their expectations? Certainly there aren’t now, but it’s an economic question: Is there economic space for the entrepreneurialism that will create jobs?

I would suggest that simply to stay alive, you have to be entrepreneurial. Every day is an entrepreneurial struggle. When people get to the cities, they try to make their own way, just as has happened in our cities. If young people, and specifically young men, can’t find a satisfactory way, you get crime and then violence.

Every day is an entrepreneurial struggle. When people get to the cities, they try to make their own way, just as has happened in our cities. If young people, and specifically young men, can’t find a satisfactory way, you get crime and then violence.

Rapid growth is possible. For example, many overseas Africans now wish to return home and bring the skills they learned back with them. Our equity fund has two wineries and 500 hectares of vineyards in Ethiopia. They had to be completely restructured and management brought in. But the only people who aren’t African in the private equity fund is me. My partners — all African, are guys who are from Boston Consulting, Harvard University, Imperial College in London. They want to bring their skills back, which is critical. They can restructure these countries and increase the workforce, increase the productivity, and increase the quality of the product. Africans are very fast learners.

You do need a decent political system, and decent people to run a decent government until you can see the benefits of this population growth.

One of the things that we’ve noticed is women are on the leading edge of entrepreneurialism, often to help their family as the head of their family. What are your thoughts on how to help women entrepreneurs in Africa? Is it greater access to capital? Knowing how to set up businesses?

Entrepreneurs grow in a fully-structured economy, when there’s a sort of middle economy.

There are very few SMEs [small-to-medium enterprises] in Africa, but there are some funds doing SMEs.

Africa has an economy at the top end, where you have global giants. And you have companies extracting resources. Then you have people scrambling for a living. Mrs. Miggins is on the street corner, and she’s got a couple of carrots, and she’s boiling up a pot with the carrots in it, and she’s calling it soup, and she’s selling it. This isn’t really even a “mom-and-pop store” economy, though in some countries like Ghana that is viable. In general, there is an economic void between the top and bottom of most economies and that space needs to cohere.

A local farmer in Zambia, part of the Nsongwe Women's Association. (Paul Morse / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

A local farmer in Zambia, part of the Nsongwe Women's Association. (Paul Morse / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

A lot of inventions gain traction in the United States because you can commercialize your invention there and sell it into the economy. That’s what you need to happen in Africa. If an entrepreneur is going to gamble and put everything into a venture, where will they sell it? Who’s going to buy their product?

That is why I did the private equity fund, to fund those mid-level companies and boost them. This goes back to your first point about the growing middle class. That growing middle class is key. The more that it coheres, the more there’s a viable economy into which entrepreneurs can put their talent and products. And there’s the cash and individuals to buy it. You get a coherent and taxable economy. The government can tax the individuals and pay for the benefits of the state.

If you say to some Africans, “What benefit do you get from taxes?” they go, “What do you mean? We’ve never seen any of that.” These notions will come about, but they cannot come about until you get that middle reach of an economy.

You mentioned your private equity fund. How have your tactics to combat extreme poverty changed? And knowing what you know now about the challenges, what would you recommend to others who want to get involved?

It’s all part of the same thing. In 1984, the day after I saw the TV broadcast, I said that to die of want in a world of surplus is not only intellectually absurd but is economically illiterate and, of course, morally repulsive.

That still is true, and it is in our interest to immediately include Africa further into the global economy. It is desperately in our interest, and, frankly, to leave it ignored and to just view it as sort of a humanitarian endeavor is misguided and certainly not what the Chinese are making a mistake in doing.

The United States must engage on a whole other level than what it’s doing now. It seriously must. This is a vast part of the world, and it is immensely to America’s benefit to engage with them. And I just don’t mean on the political level. I mean on a huge economic level.

The United States must engage on a whole other level than what it’s doing now. It seriously must. This is a vast part of the world, and it is immensely to America’s benefit to engage with them. And I just don’t mean on the political level. I mean on a huge economic level.

My personal strategy has always been to ask, “Why is this happening?” Then I use what I’ve got to try and stop what I view as sickening. So up to a point, that sort of worked, but now we have the world’s attention. Now, how do you change it?

I am a pop singer. I want to make records. I want to go and do gigs. I want to do all the stuff associated with that, but my friend and fellow Irishman Bono called me in 1999 after he’d suddenly become the master of the bloody universe. He wanted to re-engage. He said, “I’m bothered about this debt issue. Let’s do another record and concert.”

I said, “No, no. Those days are over. These are empirical issues. You’re talking about debt. These are economic issues. This is our moment, let’s use the access that celebrity now bizarrely brings.” Celebrity is just a currency. It depends on how you spend it, and so we studied with leading economists and spoke with leaders.

I kept reading these critiques about how naïve pop singers are, and that Africa’s development is all about trade. Well, it’s not all about trade. It’s about several things simultaneously.

First, charity is imperative to the human soul. To see another human hurt and to pass by is to ignore your own humanity. The most that the average individual can do is put their hand in their pocket and pull out a buck. Millions of people do that daily, and I find that invigorating. And if a million people do it, that’s political, because no politician ignores a million people. If you go with a million people in your back pocket as a package vote, any congressman is going to perk up and pay attention.

If you extend that out, nations will do multilateral, bilateral, or unilateral aid. While charity will stabilize the individual or the family, aid will stabilize a society at a basic level of health, food, and education.

While charity will stabilize the individual or the family, aid will stabilize a society at a basic level of health, food, and education.

Then, once you begin to grow a viable healthy population, you need investment. One thing leads to another. We kept getting told it’s all about trade. It’s both. You need trade, and aid to stabilize trade, to power up. That’s always been the case.

The United States is a classic example. Post-World War II, George Marshall, one of the greatest men of the 20th century, dreamt up the Marshall Plan. He persuades Congress to give Germany and Turkey and Japan and everyone else money, aid to reboot, to start again. To buy American goods and to sell to America in turn. The world economy starts picking up again. And here we are.

When these smart asses say, “Hey, aid doesn’t work. Name one country.” I say, “Excuse me? You guys are the exact beneficiaries of it: Germany, Japan, Turkey, Spain, France. The list goes on.”

So, it is all of these things. Aid, trade, politics, climatic conditions. Institutions. Law. As much as I can, I’ve been engaged in all of these issues.

We can’t help but ask this question. You were talking at the beginning about your relationships with Bono and Bob Dylan, and yet there’s your relationship with George W. Bush. How do you explain that one to people?

President George W. Bush, Bono, Mrs. Laura Bush, and Bob Geldof hold a working meeting on Africa at the G-8 Summit in Gleneagles, Scotland, Wednesday, July 6, 2005. (Eric Draper / White House)

President George W. Bush, Bono, Mrs. Laura Bush, and Bob Geldof hold a working meeting on Africa at the G-8 Summit in Gleneagles, Scotland, Wednesday, July 6, 2005. (Eric Draper / White House)

Well, first, Bono. It’s very annoying for me. Bono was this small, fat kid staring up at me when I was performing, picking his nose in the pubs of Ireland, and now I’m going to see him play to 160,000 in London. I’m sick of it. [Laughter] He’s also, besides being one of the great voices of rock, a very clever man and a true friend and comrade.

I’ve often said that George W. Bush has been the most impactful of the American presidents with regards to Africa. That’s without a question, and people are sort of dismayed when I say things like that. But the thing is, you speak truth unto power, but you also speak truth about power when it’s necessary. I admire what he did when he didn’t have to.

To die of want in a world of surplus is not only intellectually absurd but is economically illiterate and, of course, morally repulsive.

I once said to him, “Mr. President, why don’t you talk about this in the States? What you’re doing is classic Jeffersonian politics, the proper America. Why aren’t you talking about it?” He said, “Listen, Geldof, if I talk about building a bridge in Nairobi, they’ll just say, ‘Why didn’t you build a bridge in Nebraska.’” [Laughter.]

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.